The purpose of this interdisciplinary dissertation is to study and analyse the New Perspective on Paul and its aftermath from the angle of Jewish-Christian relations. Its central aim is to evaluate the underlying premises at play in Pauline interpretations with special reference to the issue of supersessionism (the question of whether the Church has replaced or is considered inherently superior to Israel), and then compare the results of that research with how contemporary Jewish-Christian dialoguers are responding to those same issues today. (Loc 2451).

- Link: Amazon

- Length: 406 (ebook location approximation)

- Difficulty: Medium, Academic

- Topic: New Perspective on Paul, Paul, Israel

- Audience: Ministers, Lay Ministers, Educated Christians

- Published: 2012

This book is a PhD dissertation written by David Bolton from Belgium which he delivered in 2011. In this book, Bolton gives a great overview of the New Perspective on Paul and a good deal of scholarship which has interacted with it. It is very fair and balanced in its appraisal.

I read it a while ago. I wasn’t so interested in Jewish-Christian relations or supersessionism when I got it. I read the book because of his interaction with the New Perspective on Paul.

This is a longer than normal contents. I’ve included a large amount of it to give you a good idea of the level of detail Bolton goes into.

Post Links

Contents

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1. PAULINE PROPAGANDA: WILL THE REAL PAUL PLEASE STAND UP?

-

-

- INTRODUCTION

- §1. OVERVIEW PAULINE INTERPRETATION UNTIL 1975

- A. CHRISTIAN OVERVIEW

- 1. The Hegelian Paul of the Tübingen school

- 2. The Kantian Paul of the Liberal school

- 3. The Greek mysteries/ Gnostic Paul of the History of Religions’ school

- 4. The Jewish Paul of the Eschatological school

- B. JEWISH OVERVIEW

- 1. Paul the Pagan-influenced Hellenist a. Kaufmann Kohler

- 2. Paul the inferior Hellenistic Jew a. Claude Montefiore b. Samuel Sandmel

- 3. Paul the rabbinic mystic a. Isaac Mayer Wise

- 4. Paul the hybrid Jew

- C. COMPARISON OF THE TWO OVERVIEWS

- D. THE LUTHERAN PAUL AND THE NAZIS

- 1. The Lutheran Old Perspective on Paul

- 2. Paul, the Nazis and the Holocaust

- A. CHRISTIAN OVERVIEW

- CONCLUSION

-

- CHAPTER 2. THE MAKING OF THE NEW PERSPECTIVE ON PAUL

-

-

- INTRODUCTION

- §1. THREE RELECTURES WITHIN NEW TESTAMENT STUDIES

- A. PAUL’S JEWISHNESS

- 1. W. D. Davies

- B. LUTHER’S READING OF PAUL

- 1. Krister Stendahl

- C. SOTERIOLOGY OF LATE SECOND TEMPLE/ EARLY RABBINIC JUDAISM

- 1. E.P. Sanders

- §2. THE NEW PERSPECTIVE ON PAUL

- A. PUTTING THE PIECES TOGETHER

- 1. James D.G. Dunn

- a. The New Perspective on Paul

- 1. Covenantal nomism was correct

- 2. Sanders’ reading of Paul was wrong

- 3. Paul critiqued covenantal nomism for ethnocentrism not legalism

- 4. The doctrine of justification was a response to the fulfilling of the Abrahamic promises by Christ

- 5. Faith in Jesus became the only identity badge needed for the new community

- 6. Good works remained important in light of the last judgment

- 7. The new covenant was an extension of the Mosaic covenant. Consequently the Church could call itself ‘Israel’

- B. HOW FAR WAS THE NEW PERSPECTIVE NEW? CONCLUSION

- A. PAUL’S JEWISHNESS

-

- CHAPTER 3. WEIGHED IN THE BALANCE: CHRISTIAN AND JEWISH CRITIQUES ON SANDERS AND DUNN

-

-

- INTRODUCTION

- §1. CHRISTIAN ASSESSMENT OF SANDERS’ COVENANTAL NOMISM

- A. GENERAL SUPPORTERS

- 1. Daniel Falk on Prayers and Psalms

- 2. Craig A. Evans on the Pseudepigrapha

- 3. Peter Enns on Scriptural expansions

- 4. Richard Bauckham on Apocalypses

- 5. Robert A. Kugler on Testaments and Donald E. Gowan on Wisdom literature

- 6. Paul Spilsbury on Josephus, David M. Hay on Philo and Markus Bockmuehl on Qumran

- 7. Martin McNamara on the Targums

- B. OPPONENTS

- 1. Mark A. Seifrid on covenantal righteousness and creational justice

- 2. Philip Alexander on Tannaitic literature and works-righteousness

- 3. D.A. Carson on the appropriateness of covenantal nomism

- C. INTERIM SUMMARY

- A. GENERAL SUPPORTERS

- §2. JEWISH CRITIQUE ON SANDERS’ COVENANTAL NOMISM

- 1. Jacob Neusner: Sanders’ work a success but trivial a. Interim summary

- §3. CHRISTIAN CRITIQUES ON SANDERS AND DUNN’S PAUL

- A. AN OVERVIEW OF POST NEW PERSPECTIVE SCHOLARSHIP

- B. OPPONENTS

- 1. Mark Seifrid defended Paul’s anthropological pessimism and covenantal nomism

- 2. S.J. Gathercole saw Paul arguing for a better atonement in Christ

- 3. Douglas Moo criticised the New Perspective’s sociological approach

- 4. Peter T. O’Brien claimed Paul not a covenantal nomist

- 5. Timo Laato on quantitative and qualitative Law keeping

- 6. D.A. Carson argued that the New Perspective was not discontinuous enough

- C. INTERIM SUMMARY D. DUNN’S RESPONSE TO THE CRITIQUES

- E. THE MULTICULTURAL PAUL OF THE NEW PERSPECTIVE SCHOOL

- §4. JEWISH RESPONSES TO THE PAUL( S) OF SANDERS AND DUNN

-

- 1. Pamela Eisenbaum – the Radical New Perspective on Paul

- 2. Mark Nanos – Paul was Torah observant

- 3. Paula Fredriksen – Paul Judaised the nations

- 4. Daniel Boyarin – Paul allegorised Judaism

-

- CONCLUSION

-

- CHAPTER 4. CHRISTIC PNEUMATISM AND SUPERSESSIONISM

-

-

- INTRODUCTION

- §1. CHRISTIC PNEUMATISM – THE DEEP STRUCTURE OF PAUL’S GOSPEL

- A. ELECTION

- B. JUSTIFICATION

- 1. Paul’s problem with covenantal nomism

- 2. Interim summary

- C. COVENANT AND SPIRIT

- 1. So what about the role of works?

- 2. Περιπατέω, Paul’s ecclesial halakha

- 3. Interim summary

- D. FINAL JUDGMENT

- 1. Exiting the new covenant?

- 2. Interim summary

- §2. THE SPECTRE OF SUPERSESSIONISM

- A. CHRISTIC PNEUMATISM IN THE DOCK

- 1. Punitive supersessionism: test case 1 Thes 2: 14– 16

- A. CHRISTIC PNEUMATISM IN THE DOCK

- CONCLUSION

-

- CHAPTER 5. JEWISH-CHRISTIAN DIALOGUE: COVENANT AND MISSION

-

-

- INTRODUCTION

- §1. THE TRAGIC COUPLE – A SHORT OVERVIEW OF JEWS AND CHRISTIANS FROM PAUL TO VATICAN II

- §2. CATHOLIC /JEWISH DIALOGUE – A CONTESTING OF THE COVENANTS

- 1. Introduction

- a. Covenant

- b. Mission

- 2. Stating the problem

- a. The choice of four models

- 3. The Conciliar and post-Conciliar teaching 1965– 1998

- a. 1960s: Vatican II’s Nostra Aetate is groundbreaking but doesn’t explicitly address the issues of covenant and mission

- b. 1970s: the Pontifical Commission’s ‘Guidelines’ advocates inclusive mission (but forgets the covenant)

- c. 1980s: ‘Notes’ denies the double-covenant model, yet states that the old covenant is unrevoked

- d. 1990s: in ‘We Remember’ the Church does ‘teshuva’ for various forms of anti-Semitism

- 4. The struggle to define a Catholic theology of Judaism continues 1998– 2009

- a. The rise of the nonmissional single-covenant model

- b. The return of missional mono-covenantalism

- c. The further development of the nonmissional single-covenant model

- d. The Good Friday prayer controversy – praying for conversion

- e. Does the United States Catholic Catechism remove the eternal validity of the Mosaic covenant?

- f. ‘A Note on Ambiguities’ opens the door to double fulfilment

- 5. Covenants in conversation: is there a way forward?

- 1. Introduction

- §3. COMPARISON WITH PROTESTANT DOCUMENTS

- 1. The World Council of Churches – little unity in its diversity

- 2. The Community of Protestant Churches – doing theology in the presence of Israel

- 3. Other Church documents and the need to distinguish between election and covenant

- 4. Jewish Christians and the Torah today

- §4. BERLIN CALLING – IS THERE STILL A WALL BETWEEN DIALOGUE AND MISSION?

- §5. TURNING TO THE THEOLOGIANS FOR HELP

- 1. R. Kendall Soulen and the economy of mutual blessing

- 2. Michael S. Kogan and the opening of the covenant

- CONCLUSION

-

- CHAPTER 6. GENERAL CONCLUSION: PAUL AMONG THE DIALOGUERS

-

- INTRODUCTION

- §1. ROUNDTABLE ONE: PAUL’S IDENTITY AND RELATIONSHIP TO JUDAISM

- §2. ROUNDTABLE TWO: COVENANT

- §3. ROUNDTABLE THREE: MISSION

- §4. ROUNDTABLE FOUR: ESCHATOLOGY

- §5. FINAL ANALYSIS

- 1. Christian identity vis-à-vis Judaism: soft supersessionism or post supersessionism?

- 2. Revelation in Pauline texts – God writes straight on crooked lines

- a. Reading beyond punitive supersessionism

- b. Stepping outside the time limits of economic supersessionism

- c. Diverse readings and new writings challenge structural supersessionism

- §6. FINAL CONCLUSION

Representative Quotes

This is a ‘short’ review from my too long epics. I’m learning to get them shorter. It’s just that a lot of the books I read have so much good content to share I feel compelled to write more about them.

This is one such example. In this case as I have done before I’ve tried a compromise by stringing along a series of representative quotes which some explanation so you can get a feel for it.

Chapter 1. Pauline Propaganda: Will the real Paul please stand up?

Bolton starts giving a historical overview of significant factors of Pauline interpretation.

McGrath remarked that Luther’s gospel, the free bestowal of justifying grace through faith, “destroys all human righteousness”. From this perspective to predicate salvation as dependent upon a decision of the human will was, for Luther, tantamount to Pelagianism. Instead it was God himself who bestowed the gift of righteousness, which is actually fides Christi (faith in Christ): “Hic vero dicit: ‘Iusticia est fides Ihesu Christi’”.

This theological understanding of Paul led to the development of Luther’s theologia crucis, with its premise that humanity was soteriologically bankrupt through an enslaved will (servum arbitrium) and needed to receive divine justification as a gift, ab extra.

For his part, Westerholm focused on Luther’s reading of the Letter to the Galatians (1516–1517), which he called Luther’s “most treasured epistle” as it contained the Reformer’s most lucid insights and reflections on Paul’s gospel. [Westerholm, Perspectives Old and New] In a nutshell, Luther claimed that the centre of Paul’s thought was the doctrine of justification by faith alone (sola fide), and that this doctrine was based on an antithesis between Law and Gospel (Gesetz und Evangelium). (Loc 4080)

As you can see right from the start Bolton is interacting with significant critics of the New Perspective.

The importance of the above is that it highlights once again how one’s hermeneutic is open to serious influence by the prevailing political-cultural climate and, vice-versa, how one’s hermeneutical prejudice may help create, sustain or further strengthen the social climate. As we saw previously in Baur’s Hegelianism, Von Harnack’s Kantianism or Bultmann’s Heideggerian Existentialism, they are all examples of the interplay between exegesis and culture, illustrating that neither stands alone, insulated from the other. (Loc 4355)

This point is a common critique the New Perspective accuses the reformers of. These days the critique is thrown both ways.

Chapter 2. The making of the New Perspective on Paul

Bolton overviews the main players in the New Perspective. He actually starts with Davies, who is a Judaism scholar prior to Sanders. But Stendahl is fairly well recognised these days.

Stendahl’s criticism of Luther’s interpretation of Paul undoubtedly made an impact precisely because it was coming from a Lutheran scholar. As we shall see in the next chapter, this in-house criticism was also the reason why strong reactions would come from the Reformed and Evangelical wings of the Church, from those who felt most threatened by it. (4646)

I didn’t know Stendahl was Lutheran prior to this point.

As a result of his research Sanders was persuaded that Paul did not offer a comparable pattern of religion like covenantal nomism. “Paul presents an essentially different type of religiousness from any found in Palestinian Jewish literature”.

His difference was not on the point of grace versus works, for on that issue Paul was actually in line with covenantal nomism. For like mainstream Judaism, Paul advocated that salvation was by grace (based on God’s prior promises to save) and that eschatological judgment was still according to works (based on one’s behavioural obedience or disobedience in light of that grace cf. Rom 2:13 NRSV “For it is not the hearers of the law who are righteous in God’s sight, but the doers of the law who will be justified”).

In this way the Law had both a negative and a positive function for Paul. “Works of Law” was not an entrance requirement, but it was a maintenance issue. One could say that it is not a condition for membership, but a condition of membership in the people of God. [Sanders, Paul, the Law, and the Jewish People] (5046)

I don’t remember Sanders specifically defining the ‘works of law’ in his Paul and Palestinian Judaism. I found this helpful.

Eventually he moves on to Dunn.

Building on the insight that the time of Abrahamic fulfilment had now come, Dunn saw Paul as developing the doctrine of justification as the means by which this fulfilment was to be implemented. Having faith in Jesus as Messiah went beyond Israel’s boundaries. Having faith in Jesus had a universal , missionary dimension that had implications for the covenant entrance of gentiles. Dunn accepted what Stendahl had written on the sociological dimension of justification, that it was a doctrine focused on the ability of gentiles to enter the covenant community without the need to first Judaise. However, Dunn saw the Pauline use of the term as going beyond that. To his mind justification was not really about initial entrance into the new covenant (which was by faith). Rather than referring to a “transfer term ,” justification was about God’s acknowledgment that the person of faith was now included in the covenant. To be justified was really a divine declaration that one was now considered as belonging to the covenant people of God, with all the benefits that brought. (5315)

Bolton doesn’t overview NT Wright’s specific contributions to the New Perspective in this section.

The next couple chapters are the best in the book and well worth its price.

Chapter 3. Weighed in the balance: Christian and Jewish critiques on Sanders and Dunn

“Though short reviews and critiques of Sanders’ work are numerous, I have chosen to focus on the systematic appraisal given in the two volume series entitled Justification and Variegated Nomism (2001, 2004). These volumes comprise over 1000 pages and represent the most sustained critique on Sanders and Dunn’s work from a Lutheran-Evangelical perspective.” (5756)

David Bolton writes about D.A. Carson’s summary of the book;

“A neat summary at the end of the volume is provided by D.A. Carson that aptly summarises the individual articles.

On the other hand it is clear that he had some difficulty hiding his own bias in favour of proving Sanders wrong and re-establishing merit theology as the common thread in Second Temple Jewish thought.

As editor in chief of the project he had expressed an explicit desire to provide a serious corrective to Sanders’ scheme.

However many of the articles had shown themselves to be in substantial agreement with Sanders’ position.” (Loc 5984)

Bolton reviews the general supporters of Sanders work in JVN:

- Daniel Falk on Prayers and Psalms

- Craig A. Evans on the Pseudepigrapha

- Peter Enns on Scriptural expansions

- Richard Bauckham on Apocalypses

- Robert A. Kugler on Testaments and Donald E. Gowan on Wisdom Literature

- Paul Spilsbury on Josephus, David M. Hay on Philo and Markus Bockmuehl on Qumran

- Martin McNamara on the Targums

Then he reviews the opponents of Sanders work in JVN:

- Mark A. Seifrid on covenantal righteousness and creational justice

- Philip Alexander on Tannaitic literature and works-righteousness

Alexander is an interesting case. Bolton reviews the results of Alexander’s work and says;

Alexander’s work “… seems to buttress Sanders’ claim that Tannaitic literature fits well within covenantal nomism as the pervasive pattern of religion.

For all that, then, it was surprising to find Alexander conclude that ‘Tannaitic Judaism can be seen as fundamentally a religion of works-righteousness, and it is none the worse for that. The superiority of grace over law is not self evident and should not simply be assumed’ (p300)

How he came to such a stark statement in light of his own article is hard to understand. It goes against the thrust of his research to that point. It seems that Alexander has slipped at the last moment into the Protestant trap of superimposing a Reformation grid on the sources (that they must reflect legalism), despite his own attempts at doing so” (Loc 5991)

Bolton then considers Carson’s summary of all the work:

“In the end Carson somewhat reluctantly admitted (just as he had begun) by stating that ‘[o]ne can scarcely fail to note the frequency with which several scholars in these pages comment that their corpora largely fit the category of covenantal nomism’ (p547).

However he immediately qualified this by saying that ‘the fit isn’t very good, especially with some part of their respective corpora’ (p547).

So his complaint was the same throughout, namely that Sanders falsely claimed that all literature 200 BCE – 200 CE fitted perfectly within the category of covenantal nomism.

The pseudo-claim ultimately gave the impression that Carson himself had not read Sanders in-depth. If he had, he would not have continued to criticise a false representation of his work.

His final comments were a gross exaggeration of the collective results produced by scholars in the volume. He claimed that the term covenantal nomism ‘is too doctrinaire, too unsupported by the sources themselves, too reductionistic, too monopolistic’ (p548).

One is tempted to claim the same for Carson’s own concluding evaluation.” (Loc 6028, ibid)

It’s helpful to appreciate that many of my peers opposed to the New Perspective have simply assumed because of the existence of this book and other reviews the New Perspective is wrong and they don’t need to worry about it.

This review is an eye opener. It shows the biggest attempt to discredit Sanders actually has ended up supporting him despite the editors bias. Sanders’ pattern of religion describing Palestinian Judaism is a good and fair reading.

Following Westerholm’s survey, there was a large group that continued to oppose the New Perspective and that for two main reasons:

- (i) the Pauline understanding of the universality of sin and the fact that human beings were incapable of fulfilling the Law properly; and

- (ii) the Pauline claim that only Christ’s atonement and the gift of the Spirit could redeem humanity’s fallenness.

Scholars such as Frank Thielman, Timo Eskola, Thomas R. Schreiner, A. Andrew Das, Timo Laato, Jean-Noël Aletti, Richard H. Bell, Seyoon Kim and, we may add to Westerholm’s survey John Piper, Simon Gathercole, Mark Adam Eliot, and Robert H. Gundry all fall within this camp.

They basically supported the original Lutheran reading that Pauline justification had first and foremost to do with an individual’s personal salvation from sin. Therefore, the vertical theological axis (one’s relationship with God) had to take precedence over the horizontal ecclesiological axis (the entrance of gentiles into Israel’s covenant). (Loc 6249)

Point (i) is partially right, partially wrong because of point (ii). It seems to me they have assumed Paul has to mean one or the other. Not that he starts from one (becoming righteous) and then moves to the other (identification of the righteous).

Seifrid [in volume 2 of JVN] surprisingly made something close to a u-turn in terms of his position in vol. 1 and was actually happy to agree that “the apostle Paul recognizes in contemporary Judaism something like the ‘covenantal nomism that Sanders describes”.

This is quite remarkable since in the previous volume he had strongly critiqued covenantal nomism as not being a suitable category, at least philologically speaking, to describe late Second Temple Judaism.

Yet now, according to Seifrid, this matrix was suddenly acceptable because it presented the perfect foil against which Paul could present his own gospel. Such a turn around is quite unwieldy and somewhat overshadows the credibility of this contribution. (Loc 6294)

Seifrid had the strongest argument against Sanders in JVN volume 1. Now we see he reneged. New Perspective authors are watched closely to see if they change their positions. If they do it is broadcast they have virtually admitted they were wrong. It’s not normally demonstrated that OPP critics do the same. Bolton has done good works here.

Chapter 4. Christic Pneumatism and Supersessionism

This is another great chapter and largely works well with my Christian framework.

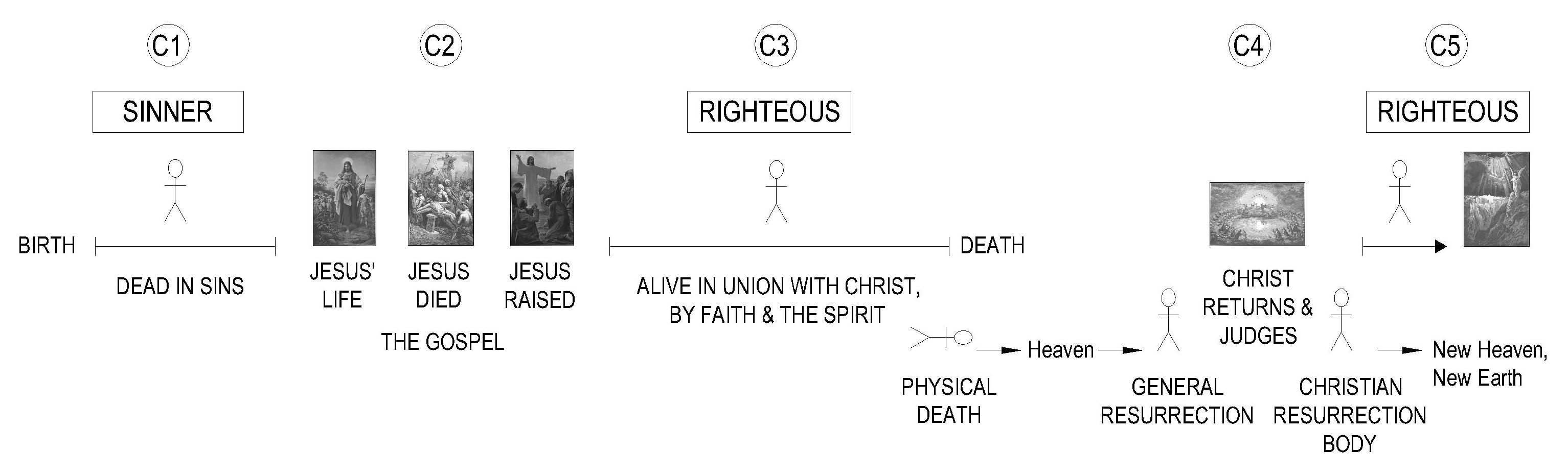

I have termed the deep structure of Paul’s thought Christic pneumatism.

Christic pneumatism is the idea that Paul’s gospel was built around two main poles, Christ and the Spirit.

Under Christ, we could place three further sub-headings, namely election, new covenant and last judgment.

Under Spirit, we could likewise place Law-fulfilment and good works.

Taken together these form what I take as the deep structure of Paul’s message. In what follows we shall address the basic elements of Christic pneumatism comprising election, justification, covenant and Spirit, and final judgment. (8071)

I agree in part with his understanding of justification below.

To a degree, I concur with Sanders that Paul’s justificatory terminology incorporated the idea of transference from one group to another (Rom 5: 8– 10; 5: 18– 19; 6: 4,7; 7: 4– 6; 8: 1f; 1 Cor 6: 9 –11; Gal 2: 16; 3: 7,14,21,26; Phil 3: 6– 11).

I think Dunn’s position that justification only referred to covenant belonging but not covenant entrance as too fine a distinction to be sustained.

One was justified by faith, and that faith brought one into the covenant, so the two are largely inseparable. It was one action of entering and belonging. In any case, such justification would entail the transference from covenantal nomism, representing mainstream Judaism, to Christic pneumatism, representing a radically transformed movement that included the basics of Judaism but had also gone beyond it. (8121)

But I would add to it that in some locations Paul does have in mind the identification of the righteous as well (e.g. Rom 3.4,27-30; 4.2-3,9,24; Gal 2.16).

Now, we have also seen previously that I understand Pauline justification as being differentiated into two main parts, namely initial/ historical justification and final/ eschatological justification.

Initial justification or entrance into (and membership of) the new covenant was by faith in (the faithfulness of) Jesus, while eschatological justification or entrance into the Age to Come was ushered in by a judgment according to works. …

It seems better to say that due to Paul’s own emphasis on the need for good works, he was not replacing “works” by Christ or the Spirit (he was not an absolute fideist), but displacing works so that they became soteriologically consequential to Christ and his Spirit.

In other words, under the Lordship of Christ and in the presence and power of the Spirit, one continued to do (good) works , though only in that right soteriological order.

Nonetheless, since the last judgment was based on works, human deeds still had great salvific significance in their own right, even if one’s works were derivative from one’s faith and not fully separable from it. Works were the fruit of one’s faith. Faith and works were distinctive without being fully distinct in Paul. (8605)

He supports the faithfulness of Christ reading of pistis Christou. I like his differentiation of initial and final justification.

Chapter 5. Jewish-Christian dialogue: Covenant and Mission

The larger amount of his book is now devoted to Jewish Christian relations. He first gives a historical survey of Protestant relations with the Jews.

This chapter sets out to present an analytical overview of Jewish-Christian dialogue as it has been developing over the last 40 years.

To keep us in line with our study of the New Perspective on Paul and its focus on justification we shall primarily concentrate on the core issues of covenant and mission.

After a brief historical introduction, we shall look at the main Catholic documents produced since Vatican II as well as at some of the principle Protestant and World Council of Churches’ documents on Christian-Jewish relations.

We shall then narrow our attention to the question of Jewish Christians/ Messianic Jews and the role of Torah in the Church before looking at two recent documents from Berlin by the World Evangelical Alliance and the International Council of Christians and Jews.

Finally we shall turn to two contemporary dialoguers , one Christian and one Jewish, to see how they can help us move forward. We conclude with the main results of our research. (Loc 10478)

Luther has a lot to repent of.

Due to their precarious belonging they suffered mass assaults during the Crusades and when the plague known as the Black Death arrived in the 14th century, Jews became the victims of a scapegoat mentality and were harshly persecuted. This was also the period of the Inquisition, the burning of Jewish books including the Talmud, conversionist sermons, blood libel accusations and the wearing of distinctive badges on clothes. [1434]

Some hope for a change in the atmosphere came with the era of the Reformation, when there was a general quickening of interest in the Hebrew Scriptures and many Protestant scholars became specialised Hebraists due to their principle of sola scriptura.

However the dark clouds could not be removed for long as was painfully epitomised by the behaviour of the leading Reformer Martin Luther himself. He first attempted to win the Jews to the Reformation cause, publishing for example, That Jesus Christ was Born a Jew (1523), but eventually turned extremely hostile against them in later life due to their failure to convert.

An example of his later works was of course his outrageous work On the Jews and Their Lies (1543) that called for the burning down of synagogues and Jewish homes and the lifting of all legal protection. (Loc 10524)

This is a good example of how the doctrine of justification by faith alone can lead to sin and cruelty.

Chapter 6. General conclusion: Paul among the dialoguers

In the last chapter Bolton sums up his his results so far.

In this general conclusion we shall compare the main findings from our Pauline research with those gathered from our dialogical investigations. This is what I call putting ‘Paul’ among the dialoguers in a series of roundtable discussions. There will be four main roundtables:

- (i) Paul’s identity and his relationship to Judaism,

- (ii) the issue of covenant,

- (iii) the issue of mission and

- (iv) eschatology.

Each roundtable shall first summarise the Pauline position(s), then compare those results with the dialogical insights before drawing conclusions. The chapter will finish with a final analysis on the topic of Pauline studies, Jewish-Christian dialogue and the question of supersessionism. There I shall present alternative hermeneutical approaches that allow for a post-supersessionist reading of Paul. (Loc 12583)

Recommendation

I recommend this book for anyone interested in getting a good overview of the New Perspective on Paul. He has an excellent understanding of the main players and covers a lot of ground.

His understanding of Paul ‘Christic Pneumatism’ is good. It reminds me of NT Wright and D Campbell.

The book is quite readable and doesn’t require the reader to know Greek.

The Kindle fonts are way too big, to read the book on an ebook read one has to reduce the font size as small as possible, otherwise it’s like reading a children’s book.

The book isn’t that long. I disagree with Amazon’s calculation of the length (600 pages+). The actual book length is hard to calculate because the Kindle ebook only displays locations and the font is massive.

Of course one would calculate 600+ page flips with a big font size.

My assessment is based on the smaller size I expect (approx 406 pages).

His writings on Jewish-Christian relations inspire sympathy and hope for better relations between the two. This part of the book will make readers more aware of Jewish scholars who are interacting with Paul.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2016. All Rights Reserved.