“The history of early Christian doctrine is basically the history of the emergence of the Christological and Trinitarian dogmas.

While the importance of soteriological considerations, both in the motivation of the development of early Christian doctrine and as a normative principle during the course of that development, is generally conceded, it is equally evident that the early Christian writers did not choose to express their soteriological convictions in terms of the concept of justification.

This is not to say that the fathers avoid the term `justification’; their interest in the concept is, however, minimal, and the term generally occurs in their writings as a direct citation from, or a recognisable allusion to, the epistles of Paul, usually employed for some purpose other than a discussion of the concept of justification itself.

Furthermore, the few occasions upon which a specific discussion of justification can be found almost always involve no interpretation of the matter other than a mere paraphrase of a Pauline statement.

The relationship between faith and works is explored, yet without moving significantly beyond a modest restatement of Paul’s original statements, in which the phrase`works of the law’ is generally interpreted as general human achievements, rather than a more specific cultic demand, peculiar to Israel’s identify.

Justification was simply not a theological issue in the pre-Augustinian tradition. …

It must also be appreciated, however, that the early fathers do not appear to have been faced with a threat from Jewish Christian activists teaching justification by works of the law, such as is presupposed by those Pauline epistles dealing with the doctrine of justification by faith in most detail (e.g., Galatians).”

(p32, McGrath, A.E., Iustitia Dei: A History of the Christian Doctrine of Justification)

Welcome to this series which will give a survey of what the early church fathers have written about justification and works of law with reference to Paul. Some sections have direct reference to justification. Others will help us get a gist of the context (textual and historical) of its use.

I call it ‘the Early Perspective on Justification’.

Including this introduction, there will be sixteen posts. One. Six. Some posts will be short, others will be long, others approach the size of Leo Tolstoy’s, War and Peace. I don’t expect many will read this series. But if you want to see what the early church fathers said about justification, here is one place to have a gander.

I will be collating my findings at the end and I will refer to these in other posts as reference. For a quick reading I suggest you read this post and the last. Then go to the posts in the middle if you want more detail.

To my knowledge no one has researched justification in the early church to this extent.

Contents

- Introduction (this post)

- Epistle of Barnabas (c.e. 70–131)

- Clement of Rome (died c.e. 101)

- Justin Martyr (c.e. 103-165)

- Ireneaus of Lyons (c.e. 125-202)

- Mathetes (c.e. 130-200)

- Clement of Alexandria (c.e. 150-215)

- Tertullian (c.e. 155-240)

- Hippolytus of Rome (c.e. 170–235)

- Origen (c.e. 185-254)

- Cyprian of Carthage (c.e. 200-258)

- Eusebius of Caesarea (c.e. 260-340)

- Ambrosiaster (c.e. 366-384)

- Pelagius (c.e. 360-418)

- Augustine of Hippo (c.e. 354–430)

- The Early Perspective on Justification

Periods in church history

The early church discussions about justification and works of law at times involve statements about various ‘dispensations’ in salvation history.

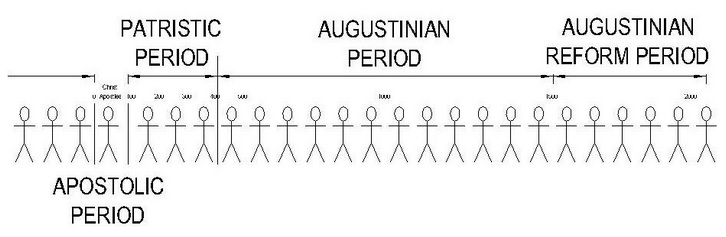

I’ve drawn a couple diagrams showing these different time periods in biblical history and what follows. The names of the periods I have given myself and are not universally adopted. I’ve given them to distinguish and show relationships between each.

- The Primeval period represents the time between creation and when God gave Abraham the law of circumcision.

- The Jewish Law period is between circumcision and the time of Jesus, the gospel.

- The Apostolic period is during the time of the Gospel and the Apostles afterwards. The early church believes the gospel is the story of Jesus, from his birth up to his resurrection and ascension.

- The Patristic Period. This is the time of the Early church I will be mainly quoting from.

- The Augustinian Period is the time from Augustine, mainly the Roman Catholic Church and up to the Protestant Reformation.

- The Augustinian Reform Period is the time from the Protestant Reformation till now.

I’m going to start from the Patristic period.

Period 4 – The Patristic Period

The Patristic Period is the time from the apostles right up to the time of Augustine.

The following diagram should help show the relationships between various people and the apostles within this time.

As you can see the early church fathers Clement of Rome and Ignatius of Antioch had direct contact with the apostles. Ireneaus and Justin Martyr knew Polycarp who knew the apostle John.

As you can see the early church fathers Clement of Rome and Ignatius of Antioch had direct contact with the apostles. Ireneaus and Justin Martyr knew Polycarp who knew the apostle John.

Normally we have only scripture to work out what the early Christians believed. The significance of these relationships should open us up to believe they had another source. The apostles themselves.

The historical context I’m interested in is the exposure of these early Christian writers to;

The historical context I’m interested in is the exposure of these early Christian writers to;

- the apostles,

- the scriptures (the Old Testament and to varying degrees the apostles writings in the New Testament),

- the early christian community with its beliefs and teachings (100 years after the apostles), and

- first and second century Jews.

The diagram above shows that the early church’s exposure to Judaism dwindled quickly in the first two centuries. I’ve largely assumed by the third century they were many Gentile communities separate from Jewish. (I realise there are some exceptions).

I think from the fourth century Christianity became increasingly a Gentile (non-Jewish) faith. With this progression, it’s logical to assume Christian arguments defending their beliefs and practices against Jews would be needed less and less and when no longer used – forgotten.

Following the apostles we should expect the concept of Chinese whispers to take effect as time passes. Only the scriptures remained. The shared Jew-Gentile-Christian context and common knowledge of the first Christian communities would fade into the past.

Where we have differences of opinion over possible and valid interpretations of scripture – especially considering interactions between early Christianity and Judaism. It makes sense to prefer the interpretations of the people immediately after the apostles than those much later.

Period 5 – Augustinian

The Augustinian Period is the time from Augustine, mainly the Roman Catholic Church and up to the Protestant Reformation.

I include Augustine and Pelagius in this time period. But it continues much beyond them. I’ve called it the Augustinian Period because of the massive influence Augustine has had on church history and in particular the Roman Catholic Church.

Period 6 – Augustinian Reform

The Augustinian Reform Period is the time of the protestant reformation. Martin Luther and John Calvin are prominent examples.

I’ve called this period the ‘Augustinian Reform’ because just as the Roman Catholic church was influenced by Augustines theology of justification, so were the reformers. The reformers were still working within an Augustinian framework when they worked out their own interpretations and theology.

In some cases I will be assessing what the early church fathers have written by comparing them against the justification framework I have discussed in my apostolic mindset series and New Perspective on Paul page.

In the next post we will look at the Epistle of Barnabas. It is traditionally ascribed to Barnabas who is mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 4.36; 9.27; 11.22; etc). It was probably written between the years 70 – 131 and addressed to Christian Gentiles. He associates the counting of righteousness with the covenant and argues Christians (Jews and Gentiles) are heirs of the covenant, not the Jews.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2015. All Rights Reserved.