“Right or wrong, the New Perspective is the most Protestant move made in the 20th Century — and by that I only mean that it seeks to get back to the Bible and challenge our beliefs in light of what we find in that Bible.” (Scot McKnight)

It is better said there is more than one New Perspective on Paul (NPP) so the expression in itself is misleading. There are new perspectives – plural. Krister Stendahl, E.P. Sanders, James D.G. Dunn and N.T. Wright are the most famous advocates of the New Perspective. They have been around for awhile, now I occasionally speak about second generation New Perspective scholars and teachers.

I’ll talk about these guys as we go along. The topic itself is big and involves a lot of integrated scriptural themes.

I’ve written some stuff more specific to Romans and Galatians in my introductions. I’m using some of it here. I’ve also written a two blog series posts called Simply Romans and Simply Galatians.

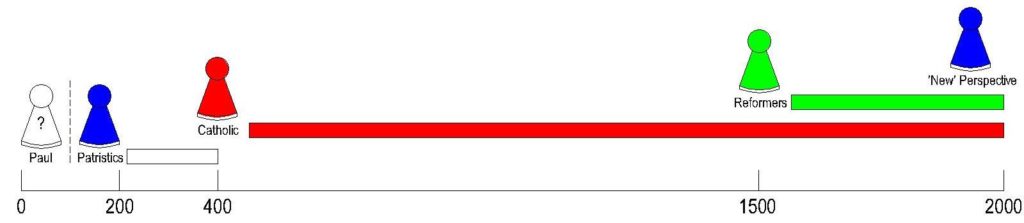

Another term used in direct comparison is the Old Perspective on Paul (OPP) This is associated with 16th Century Reformed theology. You could think of these two views (NPP and OPP) as different explanatory functions for how to understand the whole of scripture. The question is, ‘which is the better fit for the whole of scripture and makes better sense of the historical context?’

Another term used in direct comparison is the Old Perspective on Paul (OPP) This is associated with 16th Century Reformed theology. You could think of these two views (NPP and OPP) as different explanatory functions for how to understand the whole of scripture. The question is, ‘which is the better fit for the whole of scripture and makes better sense of the historical context?’

On the whole, after blogging through the bible, I don’t see the New Perspective on Paul changing a large number of beliefs Christians have held dear. A little tweak here and there. But Jesus still died for our sins, he is still the risen Lord, and believers can still have assurance of salvation.

The New Perspective has undergone some correction over the last twenty or so years. I’ve actually read a lot of these corrections, so please don’t assume I’m ignorant of the arguments involved simply because I still hold to NPP positions.

I’ve read arguments against the NPP and had to make concessions. I’ve read arguments against the NPP and disagreed because I think they are biased and wrong.

In what follows you will see my hybrid version of the New Perspective that incorporates some of those corrections, but still holds onto what I believe are the main points.

Personally I think New Perspective readings of Romans 1-4 and Galatians make better sense of the text. Scripture is our sole authority in these matters. But of course the scriptures in question have a range of hotly debated interpretations.

In light of the range of interpretations, the tipping point for why I think the New Perspective on Paul has really got ‘justification by faith’ right is early church history. Consider the question, ‘Why don’t Gentile believers in Christ have to observe the works of the Law of Moses?’ If we look to the early church fathers (c.e. 100-400) for answers, they use justification language in a strikingly similar way to the New Perspective to answer the question. As Matthew Thomas concludes in his book:

‘On these issues, the alignment between early and new perspectives is such that one can regard the “new” perspective as, in reality, the old perspective,

while what we identify as the “old” perspective represents a genuine theological novum in relation to the early Christian tradition.’ (Thomas, Paul’s ‘Works of the Law’ in the Perspective of Second Century Reception, Review)

See the summary post of my series. There is early historical precedent for thinking about justification along these lines. There is little to none for the reformed reading.

It’s more accurate to describe it as the Early Perspective on Paul. Its not new.

Perhaps this will help you understand it a little more.

Contents

Framing

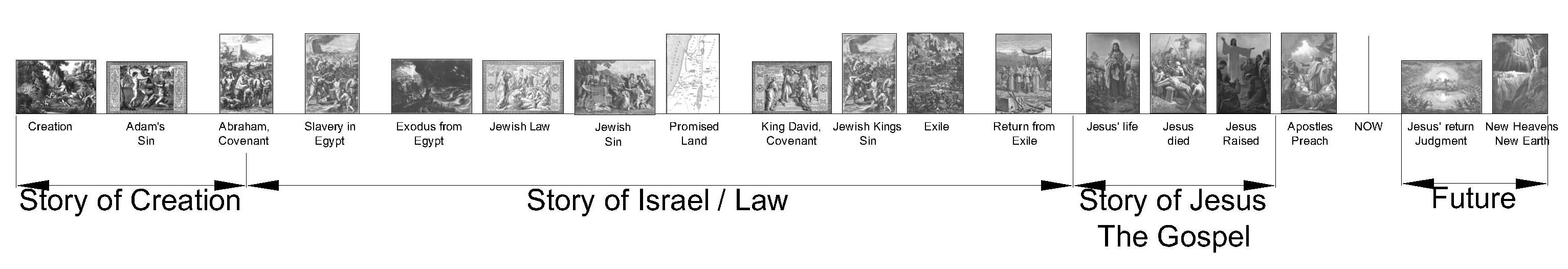

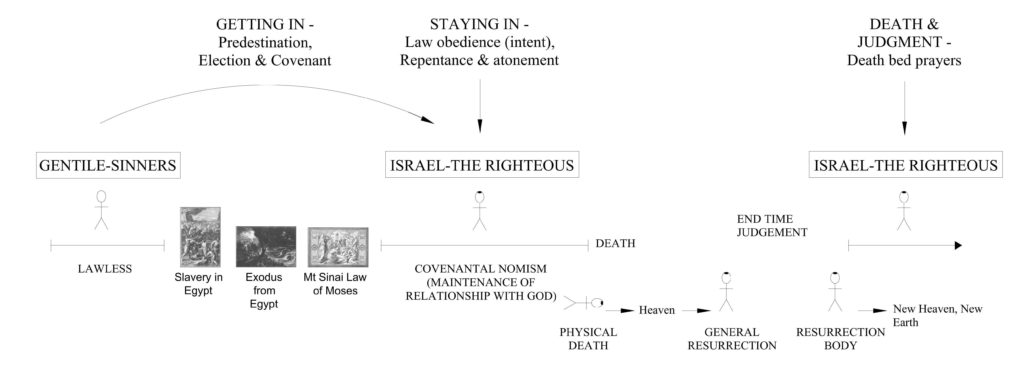

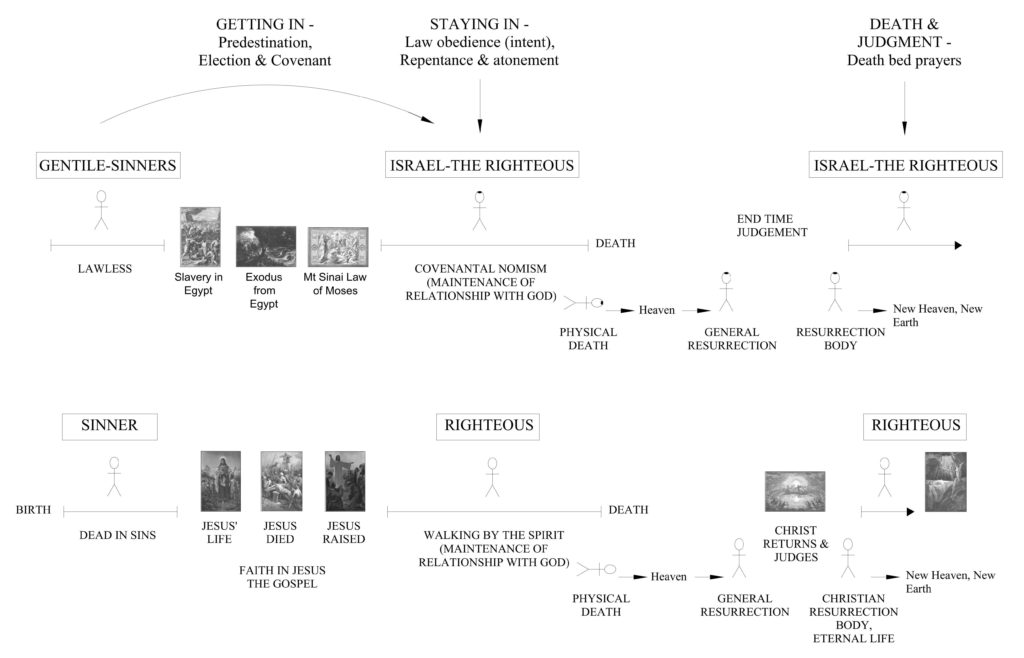

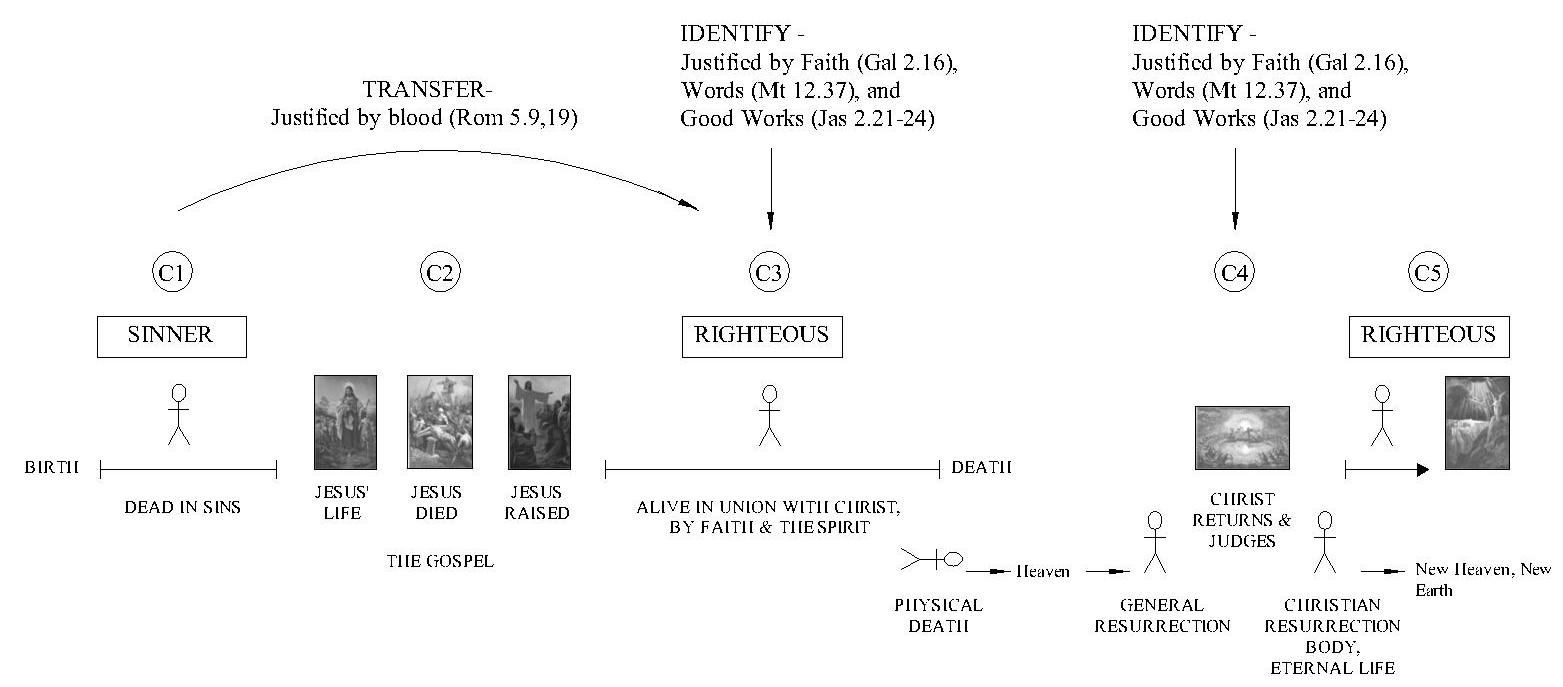

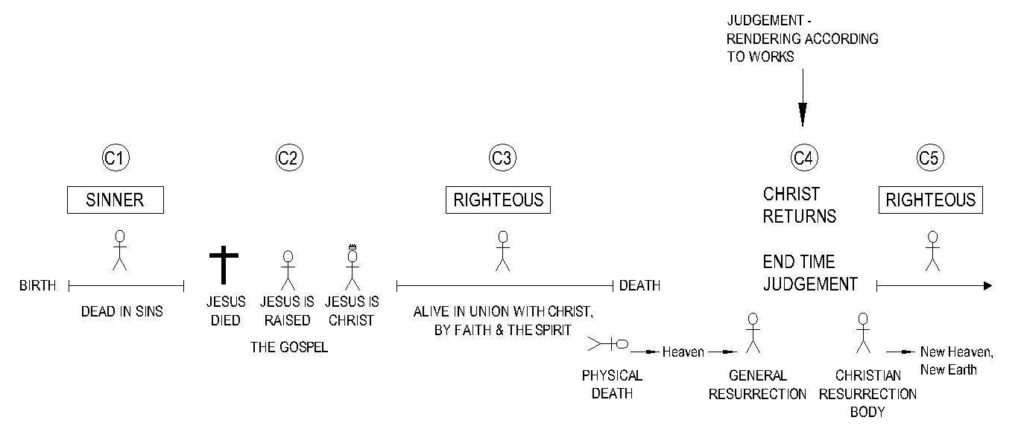

A persons theology depends on their starting framework, assumptions and questions they bring to the text. The NPP frames the way we think about scripture differently. It takes a big picture view of the scriptures and organises its motifs, themes and concepts in ways different from the OPP. Generally it adopts a salvation-historical mode of interpretation leaning more on biblical theology (overarching story) than systematic theology (concepts and topics). See the diagram of biblical events below.

History is a progressive narrative. I assume a reasonable number of NPP scholars are narrative theologians (Wright, Hays, McKnight). We look for the wider story of the bible to help us understand individual scriptures. Most of the bible can be located within this overall narrative.

History is a progressive narrative. I assume a reasonable number of NPP scholars are narrative theologians (Wright, Hays, McKnight). We look for the wider story of the bible to help us understand individual scriptures. Most of the bible can be located within this overall narrative.

Story of Creation

- God creates

- Man and woman sin

Story of Israel / Law

- God makes a covenant with Abraham and his offspring

- God rescues Israel from Egypt

- God gives Israel the covenant law

- God leads Israel into the promised land

- God raises up David’s line and makes promises

- Israel breaks the covenant and God promises/predicts something new

- Israel is punished and sent into exile

- God allows Israel back into the promised land but under foreign rule

Story of Jesus / The Gospel

- God sends Jesus

- Jesus lives, dies and rises again

- The apostles preach the gospel

Future Story

- Jesus returns to judge the living and the dead

- General and specific resurrection

- New Heavens and New Earth

Framing the Story of Israel

The overall narrative is in large the story of Israel. Related to this story is the way Paul understood Judaism.

Judaism (Sanders)

In 1977 E. P. Sanders wrote a book called Paul and Palestinian Judaism. This book in particular helps us understand the Judaism of Paul’s time.

“A New Testament scholar with a good grasp of rabbinic literature, Sanders drove the final and most powerful nail into the coffin of the traditional Christian caricature (OPP) of Judaism. Sanders’ extensive treatment of the Tannaitic literature, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha was designed, like the efforts of Montefiore and Moore, to describe and define Palestinian Judaism on its own terms, not as the mirror reflection of Christianity. Unlike Montefiore and Moore, Sanders has been immensely successful in convincing New Testament scholars.

Sanders has coined a now well-known phrase to describe the character of first-century Palestinian Judaism: “covenantal nomism.”

The meaning of “covenantal nomism” is that human obedience is not construed as the means of entering into God’s covenant. That cannot be earned; inclusion within the covenant body is by the grace of God.

Rather, obedience [e.g. keeping the law] is the means of maintaining one’s status within the covenant. And with its emphasis on divine grace and forgiveness, Judaism was never a religion of legalism.” (Mattison, Summary of the New Perspective on Paul)

Sanders understanding of Covenantal Nomism is divided into eight points:

- God has chosen Israel and

- Given the law of Moses. The law implies both

- God’s promise to maintain election and

- The requirement to obey the law.

- God rewards obedience and punishes transgression.

- The law of Moses provides for means of atonement, and atonement results in

- Maintenance or re-establishment of the covenantal relationship.

- All those who are maintained in the covenant by the intent to obey, atonement and God’s mercy belong to the group which will be saved.

Sanders’ concept of ‘getting in’ is bound up with Israel’s election and their rescue from Egypt. Here he argues God’s grace is given to Israel prior to them receiving the law of Moses and thus having to observe it.

Sanders concept of ‘staying in’ is about ‘maintaining’ ones status within in the covenant. This involves the intent to obey the law of Moses and repentance for sins which includes use of God’s provision of the Levitical sacrificial system. I assume most adherents of NPP (e.g. Sanders, Wright, Garlington) believe ‘keeping’ the law of Moses (e.g. Dt 6.18-19; cf. Josh 22.2-3) and ‘righteousness under the law’ (e.g. Phil 3.6; cf. Dt 6.25) involves:

- a regular practice of all the commands of the law,

- including the levitical sacrificial system for forgiveness of sins.

This is what is assumed when people are called ‘righteous’ (e.g. Ps 1.1-6; Lk 1.5-6; Rom 5.7)

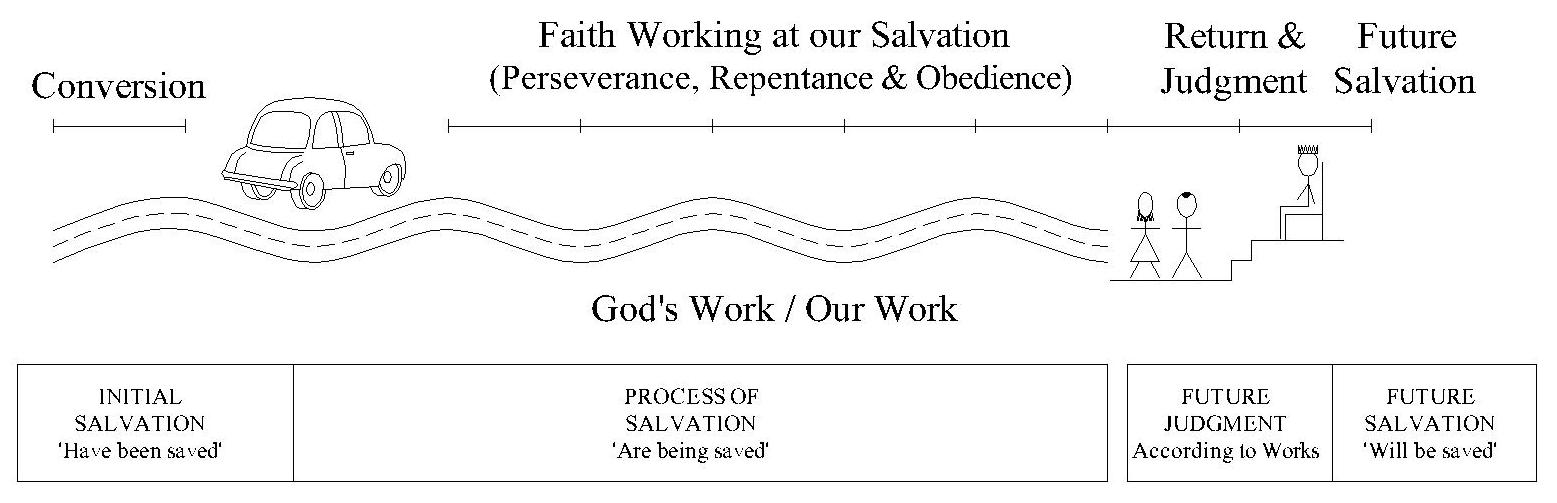

Quite controversially, Sanders has likened this understanding of maintaining ones status within Judaism to Christianity. So the question here is, “Does a Christians standing with God require ongoing ‘maintenance’ through obedience to Jesus and repentance for sin?”.

Given believers live by faith in Christ (Rom 4.12; 2 Cor 5.7) and walk by the Spirit (Rom 8.4; Gal 5.16). This does seem to conform to what Jesus and the apostles have said about the way believers should live their lives (Jn 15.10-12; Mk 8.34-35; Gal 5.6; 1 Cor 7.19; Heb 10.35-36; 2 Pet 1.10-11). Christian life involves repentance and a lot of effort (Rom 8.13; Mk 9.43-48; 1 Cor 9.27; Phil 3.12-15; 1 Jn 3.4-10). The idea of maintaining one’s status implies it requires effort to keep and people can fall away (Heb 6.1-12; 10.26-31).

There have been others who wanted to counter Sanders. Don Carson, Peter O’Brien and Mark Seifrid recruited a group of Old Testament scholars to prove Sanders wrong on his take on Judaism and Paul. Their essays formed the first of a two book series, ‘Justification and Variegated Nomism’ (JVN).

There have been others who wanted to counter Sanders. Don Carson, Peter O’Brien and Mark Seifrid recruited a group of Old Testament scholars to prove Sanders wrong on his take on Judaism and Paul. Their essays formed the first of a two book series, ‘Justification and Variegated Nomism’ (JVN).

The issues surrounding the response are technical so I won’t go into detail here. But you can find reviews of this book by;

- Don Garlington – (p240-273, Studies in the New Perspective on Paul),

- Tim Gallant – (http://www.biblicalstudiescenter.org/reviews/nomism.htm) and

- David Bolton (Justifying Paul among Jews and Christians).

- I attempted to review it as well.

David Bolton writes about D.A. Carson’s summary of the book;

“A neat summary at the end of the volume is provided by D.A. Carson that aptly summarises the individual articles.

On the other hand it is clear that he had some difficulty hiding his own bias in favour of proving Sanders wrong and re-establishing merit theology as the common thread in Second Temple Jewish thought.

As editor in chief of the project he had expressed an explicit desire to provide a serious corrective to Sanders’ scheme.

However many of the articles had shown themselves to be in substantial agreement with Sanders’ position.” (Loc 5984, ibid)

The NPP has some good points to make. Please hear them out.

The Jewish Law

Okay, so what was involved in maintaining ones status in the old covenant? Observing the law. What is the law? In another series I’ve written about the law.

“The Reformers, as most theologians today, use ’law’ to mean anything that demands something of us… What is crucial to recognize is that this is not the way in which Paul usually uses the term nomos” (Douglas J. Moo, “’Law,’ ‘Works of the Law,’ and Legalism in Paul,” Westminster Theological Journal 45, no. 1 (Spring 1983) : 88.)

According to the OT scriptures, what is the law?

“The OT has a variety of terms for ‘law’, the commonest of which are: tôrāh, ‘law, instruction, teaching’; hōq, ‘statute, decree’; mišpāt, ‘judgment, legal decision’; dābār, ‘word’; miṣwāh, ‘command (ment)’. Their number reflects the importance of law within the Bible.

The first five books are called tôrāh, ‘law’, by Jews and the NT, even though they appear to be as much about the story of the Jews as law. The specifically legal sections are embedded in narratives about Israel’s early history, and this context is important for the understanding of biblical law.”[Wood, D. R. W., & Marshall, I. H. (1996). New Bible dictionary (3rd ed.) (672)]

The NPP in particular readily accepts that ‘Law’ in many cases refers to the Pentateuch narrative.

The phrase ‘the law and the prophets’ also occurs in Mt 5.17; 7.12; 22.40; Lk 16.16; Jn 1.45; Acts 13.15; Rom 3.21 and denotes the OT scriptures as a whole.

In a large number of cases the use of the term ‘law’ refers to the Sinaitic covenant (e.g. 2 Ki 22.8; 23.2,21). Embedded in the law (as the story of the Jews) are the commands of the law (Lk 2.22-24, 27,39; Rom 2.12-27; 1 Cor 9.8-9).

For Paul the ‘law’ (nomos) could mean either;

- the story of the Jews describing an era of time from Moses to Jesus recorded in scripture (Rom 3.10-18; Gal 4.21; 1 Cor 14.21), or

- a set of commands given within this time period to the Jews (e.g. Rom 2.23,25; 7.12), or

- another set of ethical principles (1 Cor 7.19 ‘commandments of God’; 1 Cor 9.21 ‘law of God’, ‘law of Christ’), or

- a rule or principle (e.g. Rom 3.27 ‘law of faith’; Rom 8.3 ‘law of sin and death’)

The two concepts of law (story and commands) are interwoven together. Just read Genesis through to Deuteronomy.

Commands in the Law of Moses

The following list describes most of the commands in the Law of Moses. It’s a simplified breakdown of the 613 mitzvot compiled by Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon in the Mishneh Torah.

- Love God and Neighbour

- Honour Parents

These two seem to refer more to attitudes that potentially lead to various actions rather than actions themselves.

- Circumcision

- Festivals and holidays

- Worship and Sacrifice

- Purity and Washings

Other than circumcision, these commands involved regular works and deeds throughout the entire calendar year. Circumcision and Sabbath observance also functioned as signs.

- Idolatry and Foreign Worship

- Sorcery and Divination

- Murder and Violence

- Sexual Immorality

- Stealing

- False Witness and Dishonesty

- Coveting

- Food laws

These commands are all prohibitions against some sort of behaviour. They were behaviours people should not do.

- Firstborn

- Property, Land and Servants

- Punishment and Restitution

- Social Justice and the Poor

- Vows

- Trumpets

- Clothing

- War practices

This last groupings of commands did not involve regular practice for most of the people. They seemed to be irregular. Only on certain events were they required.

The Israelites (including Paul) on the whole thought of the law of Moses as a unity. When they referred to the commands in the law, their use of ‘law’ reflects the whole law. But on occasion they did speak of specific sections in the law of Moses, not the whole.

e.g.

- The Decalogue,

- when they refer to ‘unclean’ (Cleanliness and Purification laws)

- Acts uses the word ‘customs’ (6.14; 21.21; 26.3; 28.17)

- when the refer to sacrifices and offerings (temple laws)

- ‘sexual immorality’ (forbidden sex acts in the law)

- ‘days, months, seasons years’ Gal 4.10 (Jewish calendar observances), ‘a festival’ Col 2.16 (Jewish holidays and festivals)

- ‘Food or drink’ (Col 2.16) ‘Never eaten anything unclean’ Acts 10.14 food laws

- works of law, ‘works’ are observable actions, not what I’ve described as the attitudes or prohibitions.

Works of law (Dunn)

It was James D.G. Dunn who made the expression ‘New Perspective on Paul’ famous. He was the first to speak about Paul’s expression ‘works of law’. Paul uses the term ‘works of law’ (ἔργων νόμου) in a number of important texts (Rom 3.20,28; Gal 2.16; 3.2,5,10). Some of which relate to justification.

It was James D.G. Dunn who made the expression ‘New Perspective on Paul’ famous. He was the first to speak about Paul’s expression ‘works of law’. Paul uses the term ‘works of law’ (ἔργων νόμου) in a number of important texts (Rom 3.20,28; Gal 2.16; 3.2,5,10). Some of which relate to justification.

Dunn claims that,

“‘Works of law’, ‘works of the law’ are nowhere understood here, either by his Jewish interlocutors or by Paul himself, as works which earn God’s favor, as merit-amassing observances.

They are rather seen as badges:

- [1] they are simply what membership of the covenant people involves,

- [2] what mark out the Jews as God’s people;

…in other words, Paul has in view precisely what Sanders calls ‘covenantal nomism.’ And what he [Paul] denies is that God’s justification depends on ‘covenantal nomism,’ that God’s grace extends only to those who wear the badge of the covenant (Ibid., p. 194).

The “badges” or “works” particularly at issue were those of circumcision and food laws, not simply human efforts to do good. The ramifications of this observation for traditional Protestantism are far-reaching:

More important for Reformation exegesis is the corollary that ‘works of the law’ do not mean ‘good works’ in general, ‘good works’ in the sense disparaged by the heirs of Luther, works in the sense of achievement…

In short, once again Paul seems much less a man of sixteenth-century Europe and much more firmly in touch with the reality of first-century Judaism than many have thought (Ibid., pp. 194, 195).

Personally I think referring to the works of law as ‘boundary markers’ or ‘badges of covenant membership’ unhelpful. They are that, but there is more to it. Firstly, the scripture doesn’t use this terminology. I prefer to use the terms the scripture uses. Second the terminology distracts us from thinking that neglecting to obey these commands was sin.

Overall however, I see what he’s getting at. Here’s what I think.

The expression is not defined in the scriptures. I suspect however, what Paul refers to as ‘works of law’ are termed ‘customs’ in Acts 6.14; 21.21; 26.3; 28.17. I’ve produced this table to look at the underlying Greek words of the expression and what they are translated to mean in English.

| Greek | ἔργων | νόμου |

| Transliteration | ergōn | nomou |

| English | work, deed | law |

Let me take you through various steps to help you understand what Paul means by ‘works of law’.

1) Law

Paul is referring to the Law of Moses. This is the covenant law God commands in the Pentateuch and given to the Jews at Mt Sinai. The terms ‘law’ and ‘covenant’ are virtually synonymous in the OT.

2) Works

Paul refers to ‘works’ or ‘deeds’ specified in the law of Moses. These are God’s commands in the Jewish law that involve observable actions, works and deeds. Things the people of Israel were commanded by God to do.

Note from above, not all the commands in the law actually involve people doing something. Some times they were commanded not to do something (e.g. Do not steal). Consequently I find it hard to believe the expression ‘works of law’ includes the prohibitions in the law of Moses and therefore it cannot refer to all the commands in the law of Moses.

3) Partial Observance of the Law of Moses

Paul uses the expression in Galatians several times. In this letter he refers to circumcision (Gal 2.3-5; 5.2-3), observance of various Jewish festivals and Sabbaths (Gal 4.9-10).

Paul’s argument in Galatians presupposes the Galatians were not relying on or observing all the commands of the law of Moses. Because he says if they accepted circumcision they would have to observe the whole law (Gal 5.3).

Likewise in Romans, Paul’s writings suggest some Jews believed observance of the ‘works’ (of law) was all that was required for righteousness under the law (Rom 9.31-32; cf. Mt 23.23).

4QMMT (link) states the same where the writer encourages his audience in the practice of ‘some works of law’, not all, practice of some of the works of law he believed would avail for their future justification. Hence some Jewish groups believed not all of the law of Moses had to be observed for justification.

Paul opposed this belief (Rom 3.19-20) highlighting where they fell short (Rom 2.21-23; 3.19-20).

(Note in contrast Zechariah and his wife are depicted as righteous before God because they kept all the commands of the Lord in Lk 1.5-6).

It seems plausible to me to think there were some Jews who were not observing the whole law of Moses, rather they only relied on the works of law (Gal 3.2,5,10a; 6.13). I assume that Paul like many Hebrews believed some kept the law. But he said the Galatians would come under the Deuteronomic curse if they relied on the works of law (Gal 3.10) because they needed to observe the whole law of Moses and not just part of it.

Note: the commands of circumcision, festival and Sabbath observance recall various events in the Jewish story of salvation and are used as ‘signs’ to identify the Jews as God’s people and point them to the LORD (Gen 17.11; Ex 31.13,17).

4) Differing responses to differing works

When Paul hears the Galatians have returned to observing various seasons and festivals (Gal 4.10) he vehemently opposes the idea Gentile believers have to observe the ‘works of law’ arguing their salvation is at stake.

On the other hand, when he finds out believers are doing good and resisting sin he praises them. Paul has no problem with Gentiles of all churches observing what I’ve described as the attitudes (love, honour; Gal 5.6,14; Rom 13.8-10; 1 Cor 16.22; Eph 6.1-2) and most of the prohibitions (idolatry, stealing, adultery; Gal 5.19-21; cf. 1 Cor 6.9-11; Eph 5.5-6). I don’t think Paul would object to Gentiles helping the poor and needy as well (cf. Gal 2.10).

I should note at this point there is an overlap between the law of Moses and what Jesus and the apostles instruct in the New Testament, what I will refer to as the ‘law of Christ’ (e.g. 1 Cor 9.21; cf. 1 Cor 7.19; Mt 28.20). That is, there are commands and prohibitions in the law of Moses (Israel only) that have been retained in the law of Christ (all nations). For example, the commands to love God and neighbour, honour ones parents and the prohibitions of sexual immorality, idolatry, etc.

My point is – Paul is only reacting to the observance of a specific set of commands in the law of Moses. Not every one.

When he sees Gentiles being loving or resisting idolatry he doesn’t react in the same way or think resisting this sin means a return to Judaism or constitutes a danger to their salvation. Quite the opposite in fact (Gal 5.19-21). I think if he learned they were being observed because they were in the law of Moses, he would strongly object. But their mere observance presents no problem, probably because they are part of the law of Christ.

Summarising here: Paul doesn’t associate observance of every command in the law of Moses with his expression ‘works of law’ or a return to Judaism. He has a definite subset of observable actions commanded in the law of Moses in mind. We can derive this by the way he responds to observance of differing commands in the law. Do you think Paul would have reacted as strongly as he did if he heard the Galatians were observing Lev 19.18 as he did Lev 23?

5) Good works?

Paul’s understanding of ‘works of law’ does not include what he describes as ‘good works’ or helping the needy either. Through instruction and his conduct Paul insists believers of all stripes continue in these works (Gal 2.10; 6.7-10; Tit 3.8,14) and commonly lets his audiences know the last judgment will be according to them (Gal 6.7-10; Rom 2.6-10; 2 Cor 5.10).

Looking at all the commands in the law of Moses, the most prominent ‘works of law’ in my opinion are therefore: Circumcision, Festivals and Holidays, Worship and Sacrifice, Purity and Washings.

6) Moral obligation

The works of law are part of the law of Moses God commanded. The Jews consequently believed the observance of works of law was an ethical and moral obligation on all people. They are part of the law God commanded. Hence the following commands of God in the law of Moses:

About Circumcision: “Any uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin shall be cut off from his people; he has broken my covenant.” (Gen 17.14)

About the Festivals and Holidays: “Three times a year all your males shall appear before the LORD your God at the place that he will choose: at the Feast of Unleavened Bread, at the Feast of Weeks, and at the Feast of Booths. They shall not appear before the LORD empty-handed.” (Dt 16.16)

About Worship and Sacrifice: “And this shall be a statute forever for you, that atonement may be made for the people of Israel once in the year because of all their sins.” (Lev 16.34)

About Purity and Washings: “If the man who is unclean does not cleanse himself, that person shall be cut off from the midst of the assembly, since he has defiled the sanctuary of the LORD. Because the water for impurity has not been thrown on him, he is unclean. And it shall be a statute forever for them.” (Num 19.20-21)

One difference between the scriptures view and the OPP is that the OPP tends to emphasise works as merit amassing observances used to earn a righteous standing in God’s eyes.

In the scriptures however these ‘works of law’ were obligatory. They were commanded by God. One has to do these works because, not doing them was an omissional sin in Jewish eyes. A person commits a sin of omission when they are commanded to do a work or deed by God and they fail to do so.

17 So whoever knows the right thing to do and fails to do it, for him it is sin. (Jas 4.17)

The reformed (OPP) understanding about works of law being merit amassing observances used to gain righteous standing is wrong. God commanded these works. Not to do them is sin. This applies to anything God commands of this people.

Consequently for the Jews, observance of the works of law were a salvation and a fellowship issue particularly for Gentile who did not observe them. Continued and deliberate sin is a problem for any of God’s people (e.g. Gal 5.19-21; Heb 10.26-31) and God’s people are to avoid people who call themselves believers who continue in a lifestyle of sin (1 Cor 5.11; cf. 1 Cor 6.9-11).

Because the Jews thought Gentiles were continually sinning by not observing these commands they would logically deny they would be saved (cf. Acts 15.1; Gen 17.14) and refuse to be in fellowship with them (e.g. Acts 10.28; Gal 2.11-14; Rom 14.1-23; Col 2.16-23). From their point of view Gentiles had to practice them regularly to maintain their covenant standing with God and thus be saved.

In Justin Martyr’s Dialogue with Trypho the Jew, Trypho expresses this problem the Jews had towards Gentile believers;

“But this is what we are most at a loss about: that you, professing to be pious, and supposing yourselves better than others, are not in any particular separated from them, and do not alter your mode of living from the nations, in that you observe no festivals or sabbaths, and do not have the rite of circumcision; and further, resting your hopes on a man that was crucified, you yet expect to obtain some good thing from God, while you do not obey His commandments.

Have you not read, that soul shall be cut off from his people who shall not have been circumcised on the eighth day? And this has been ordained for strangers and for slaves equally.

But you, despising this covenant rashly, reject the consequent duties, and attempt to persuade yourselves that you know God, when, however, you perform none of those things which they do who fear God”.

(Justin Martyr. (1885). Dialogue of Justin with Trypho, a Jew. In A. Roberts, J. Donaldson, & A. C. Coxe (Eds.), The Ante-Nicene Fathers: The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus (Vol. 1, p. 199). Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company.)

In the historical context the Jews regularly practiced the works of law, in some cases thinking them more important than the commands relating to justice, mercy and faithfulness (Mt 23.23-28).

With respect to the Gentiles, Paul believes observance of the works of law is primarily a salvation issue (Gal 3.3,10; 5.1-4). He insisted they must not observe these commands because they undermine the gospel (Gal 1.6-10) and they could fall away from grace if they practiced them (Gal 5.4). But the Jews are allowed to continue practicing them (Rom 3.31; Acts 21.20-24) as long as they didn’t rely on them (Gal 3.10).

So in the historical context Gentile believers were caught in the middle.

Most Jews believed Gentiles were sinning by not observing them, but Paul believed they would be severed from Christ if they did observe them.

Dikai Word Group

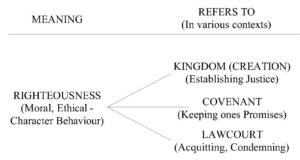

Dikai is the Greek root of many words translated as ‘righteous’, ‘righteousness’, ‘justified’ and ‘justification’. Typically I have several concepts in mind for understanding how they fit into scripture and how they were understood by people in the historical context of the New Testament.

(Note: I do not think there is a one to one correspondence with these Greek nouns, verbs and the concepts I associate with them. What I am attempting to do here is establish a rough match and framework for understanding how they work together.)

The Greek nouns δικαίου (Trans. dikaiou) and δίκαιος (Trans. dikaios) I understand to be individuals (e.g. ‘A righteous person’, ‘the righteous one’ – Rom 1.17; 5.7; Gal 3.11; 1 Pet 4.18). The noun δίκαιοι (Trans. dikaioi) I understand to be a group of people (e.g. ‘the righteous’ – Rom 2.13; 5.19; Lk 1.6).

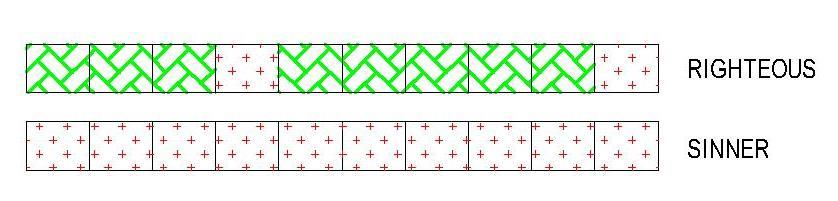

The ‘righteous’ in scripture are commonly contrasted with the ‘sinners’ and the ‘ungodly’ (e.g. Lk 15.7; Rom 5.7-8; 1 Tim 1.9; 1 Pet 4.18). It is the righteous who in the future will inherit the kingdom of God and enter into eternal life (Mt 13.43; 25.46; Lk 14.14).

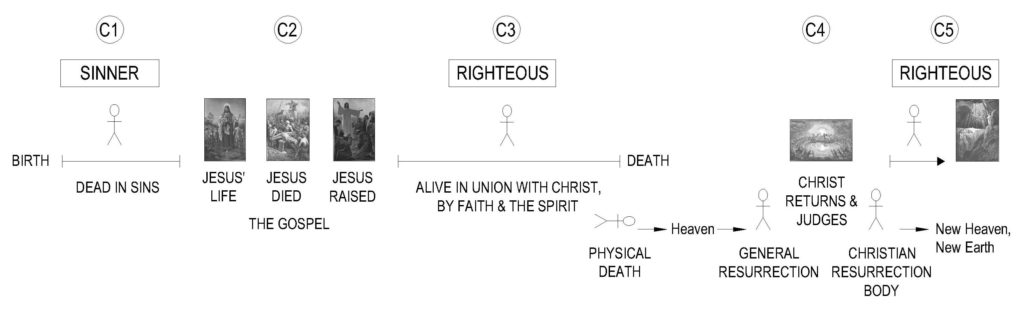

Consequently I distinguish ‘the righteous’ with ‘sinners’ by using the following timeline.

The Greek verbs δικαιοσύνη (Trans. dikaiosynē), δικαιοσύνην (Trans. dikaiosynēn), δικαιοσύνης (Trans. dikaiosynēs) and δικαιώματος (Trans. dikaiōmatos) describe some sort of behaviour or action (e.g. Mt 5.6, 20; 6.1; Lk 1.75; Rom 1.17; 3.21; 6.18-19; 2 Cor 5.21) done by the righteous.

The verbs rendered in English as ‘justified’ I follow the conventions below.

The verbs δικαιωθῆναι (Trans. dikaiōthēnai), δικαιούμενοι (Trans. dikaioumenoi), δικαίωσιν (Trans. dikaiōsin), δεδικαίωται (Trans. dedikaiōtai), ἐδικαιώθητε (Trans. edikaiōthēte) and Δικαιωθέντες (Trans. dikaiōthentes) I understand in these verses to be associated with sinners becoming righteous, or setting things right (e.g. Acts 13.39; Rom 3.24; 5.1,9,18; 6.7; 1 Cor 6.11; Tit 3.7).

The verbs δικαιοῦται (Trans. dikaioutai), ἐδικαιώθη (Trans. edikaiōthē) and ἂν δικαιωθῇς (Trans. an dikaiōthēs) I understand in these verses to be the identification of people who are righteous, those have been set right or are in the right (Mt 11.19; Jas 2.21,24-25; Rom 3.4; 4.2; Gal 2.16; 3.11).

Likewise I associate the verbs δικαιωθήσῃ (Trans. dikaiōthēsē), δικαιωθήσονται (Trans. dikaiōthēsontai) and δεδικαίωμαι (Trans. dedikaiomai) in these verses to depict people being deemed righteous in the future judgment (Mt 12.37; Rom 2.13; 1 Cor 4.4).

Consequently I distinguish between these justification events by modifying the timeline above.

I’ll now go into a little more detail on these concepts.

People

As mentioned previously, the term ‘righteous’ is commonly applied to individuals (a ‘righteous person’; e.g. Rom 5.7), a group of people (‘the righteous’; e.g. Rom 2.13) and God (God is righteous).

- When applied to an individual person, these nouns normally carry moral overtones and are frequently associated with being upright and the regular practice of some sort of moral standard.

- When applied to a group of people, it is commonly synonymous with the covenant people of God. The righteous inherit God’s promised kingdom.

In many cases it reflects notions of Identity, character and behaviour of individuals or a group of people.

I’ll start with my summary position on what it means the be righteous and then I’ll go about demonstrating how this fits with scripture. In summary ‘the righteous’ [plural]:

- ‘Walk with God’ – Key concept: RELATIONSHIP WITH GOD. They are governed by God the King and live under his dominion. They take refuge and trust in him. They enjoy His covenant blessings.

- ‘Practice righteousness and do not keep on sinning’ – Key concept: PRACTICE OF RIGHTEOUSNESS. Here I emphasise the presence of righteousness in a persons life, rather than the absence of sin. Clearly they adhere to some sort of ethical standard, and

- Are ‘blameless and innocent’ – Key concept: BLAMELESS. They have no record of debt against them (through both obedience in avoiding sin and sacrifice to atone for sin).

Relationship with God (God’s family)

The righteous are commonly depicted as God’s people in scripture. If we look at scripture we see the righteous are described as;

- God’s people (Ps 14.5-7; 94.14-15; 125.2-3; Lk 1.75-77; cf. Ps 106.3-5; Isa 26.7-11; 32.16-18; 56.1-3; 60.20-21),

- God’s nation (Ps 33.1,12; Isa 26.2; 58.1-2; cf. Je 31:23),

- God’s servants (Ps 34.21-22; Mal 3.17-18), and

- God’s saints (Ps 31.18,23; 37.27-31; 97.10-12; Rev 19.8).

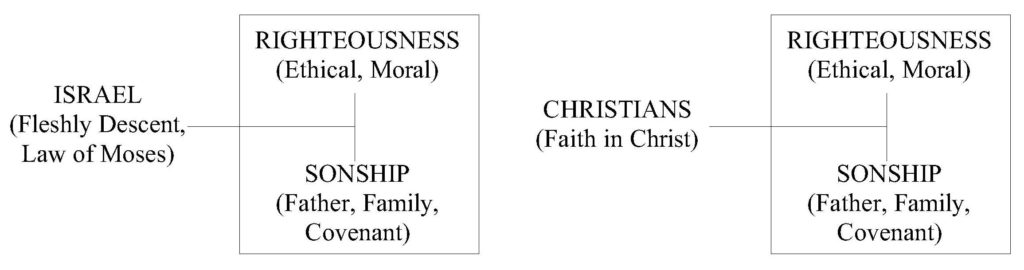

There is the saying, ‘Like father, like son’. The concept suggests that sons behave in the same way as their fathers do (e.g. Jn 8.39-44). In many instances the ethical and familial associations are bound together in the one concept (e.g. Mt 3.9; 12.50; Lk 3.7-8; 1 Pet 1.16-17; cf. Wis 2.12-18). That is to say there is a close relationship between righteousness and sonship. The apostle John and Jesus could not be clearer (1 Jn 3.7,10; Mt 13.43).

43 Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father. (Mt 13.43)

Sonship is at times, synonymous with righteousness. This clearly differs from the ‘recognised standard’ definition associated with weights and rules. Weights and rules cannot be God’s sons, but the righteous are. Thus in some instances the ethical and familial associations are bound together in the one concept (e.g. Lk 3.7-8; 1 Pet 1.16-17).

Covenant

Being ‘righteous’ in some passages also carries covenantal connotations.

For most of the scriptures, the ethical connotations associated with righteousness are based on the covenant law (e.g. Ps 1.1-6). In a forensic or law court setting (e.g. Dt 25.1), breaking the law is synonymous with breaking the covenant (e.g. Lev 26.14-15). Generally then, ‘righteousness’ denotes a moral status which according to the Hebrew authors of scripture was defined by the obligations of the covenant (Dt 5.1-3 ‘covenant’, ‘rules’; 6.25 ‘righteousness for us’). Before the law of Moses was given there were still people called ‘righteous’ (e.g. Gen 6.9; 18.22-33). Are they still under the covenant in some way? Yes. The author of Hebrews describes the righteous before the law of Moses as coming under the covenant promises and inheritance (Heb 11.4,7,13,39).

Likewise I assume all the righteous are beneficiaries of God’s covenant promises and will inherit the kingdom to come. In Paul, inheriting the kingdom of God is predicated on being righteous (1 Cor 6.9-10). The key issue here is that being one of ‘the righteous’ means they are of God’s covenant people and inherit the covenant promises (land). (See also Ps 37; Mt 12.49-50; Rom 8.15-16; 1 Pet 1.3; Heb 11).

There is a stream of thought within covenant theology where covenants are said to form familial bonds. Think of marriage as a covenant bond which makes a husband and wife, family. Similarly, because God made a covenant with Abraham, Israel is now his son (Ex 4.22-23; Dt 14.1; Hos 11.1). Scott Hahn is one advocate of this. He argues a covenant is a means of establishing a kinship relationship between two parties. See my review of his book.

We should keep this in mind as we read Rom 4.9-12.

9 Is this blessing then only for the circumcised, or also for the uncircumcised? For we say that faith was counted to Abraham as righteousness. 10 How then was it counted to him? Was it before or after he had been circumcised? It was not after, but before he was circumcised. 11 He received the sign of circumcision as a seal of the righteousness that he had by faith while he was still uncircumcised.

The purpose was to make him the father of all who believe without being circumcised, so that righteousness would be counted to them as well, 12 and to make him the father of the circumcised who are not merely circumcised but who also walk in the footsteps of the faith that our father Abraham had before he was circumcised.(Rom 4.9-12)

Paul says the purpose of Abraham’s faith being counted as righteousness was to make him the father of all who believe.

Abraham’s counting of righteousness established his fatherhood over all who would believe. Jews and Gentiles. They would be counted righteous and as his offspring because of their faith.

Likewise in Galatians (Gal 3.6-9) Paul says the Gentiles have become ‘sons of Abraham’. Paul is explicit that those of faith are the sons of Abraham.

6 just as Abraham “believed God, and it was counted to him as righteousness”? 7 Know then that it is those of faith who are the sons of Abraham. 8 And the Scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, preached the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, “In you shall all the nations be blessed.” 9 So then, those who are of faith are blessed along with Abraham, the man of faith. (Gal 3.6-9)

Faith confers righteousness and sonship in Paul’s thought. The two are inseparable.

Traditionally, Israel was considered God’s son (Ex 4.22; Dt 14.1; Hos 11.1). In Romans 9, Paul acknowledges this by saying they were adopted (Rom 9.4-5). He then implies, that just as righteousness is now counted to Jews and Gentiles who believe, so is being one of Abraham’s offspring counted to Jews and Gentiles (Rom 9.6-8).

8 This means that it is not the children of the flesh who are the children of God, but the children of the promise are counted as offspring. (Rom 9.8)

I wrote a post on Paul’s use of this verb in Romans 4. Just as Paul uses logizetai to describe God regarding Abraham’s faith as righteousness. So to does he use the verb with respect to Abraham’s offspring.

I’m not denying the ethical and moral overtones associated with righteousness or its general meaning. I’m adding to that understanding, saying that in some contexts the ethical and familial connotations are inseparable and in Romans 4 the familial connotations are quite important.

Practice of Righteousness

Another important distinction I hope to make is being righteous is more about the presence of righteousness in a persons life, rather than the absence of sin.

Holiness, ethically and cultically speaking, is the absence of defilement or blemish (separation from what displeases or provokes the holy God).

It would generally fall to words such as righteousness to capture the active aspects of Christian ethics, the positive pursuit of good works, acts of love and service, and the like. (297, DeSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship and Purity)

(Note: I’ve depicted sinners as doing nothing right following the implications of Rom 8.7; 14.23; Heb 11.6).

6 No one who abides in him keeps on sinning; no one who keeps on sinning has either seen him or known him.

7 Little children, let no one deceive you. Whoever practices righteousness is righteous, as he is righteous.

8 Whoever makes a practice of sinning is of the devil, for the devil has been sinning from the beginning. The reason the Son of God appeared was to destroy the works of the devil. 9 No one born of God makes a practice of sinning, for God’s seed abides in him; and he cannot keep on sinning, because he has been born of God.

10 By this it is evident who are the children of God, and who are the children of the devil: whoever does not practice righteousness is not of God, nor is the one who does not love his brother.(1 Jn 3.6-10)

The righteous make a practice of righteousness (1 Jn 3.7). Zechariah and Elizabeth were righteous before God in part because they walked blamelessly in all the commandments of the Lord (Lk 1.5-6). It is the doers of the law who will be justified (Rom 2.13).

The scriptures tend to look at a person’s general character of life in order to work out if they are righteous of not.

50 Now there was a man named Joseph, from the Jewish town of Arimathea. He was a member of the council, a good and righteous man, (Lk 23.50)

The Old Perspective on the other hand looks for sin. They assume that the presence of any amount of sin suggests the person is a sinner. I believe this understanding runs contrary to scripture. Refer to my word studies on righteous, good and sinner for further information.

Blameless

I think the scriptures assume the righteous can still sin (e.g. Ecc 7.20; Eze 18f; Jas 3.2), but their sin is forgiven. For this reason I say their is no sin in view. Paul, when describing his former life says;

6 as to zeal, a persecutor of the church; as to righteousness under the law, blameless. (Phil 3.6)

The key idea here is that being ‘blameless’ does not mean perfection. In both covenants being blameless involved both obedience to God’s commands and utilising the available system of atonement for sin.

Righteousness

Look up a biblical dictionary and you will see ‘righteousness’ typically denotes

‘the state or quality of that which accords with some recognised standard’ (Righteous, Righteousness, Mounce’s Complete Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words).

The term has moral connotations and conforms to some sort of standard. But what standard?

I’ve done a word study on righteousness in the scriptures here. I found it’s possible for a word to have a general meaning, but also be employed in different contexts in specific ways. With respect to righteousness I found a series of inter-relationships. In particular the themes of Kingdom and Covenant are helpful in seeing how things fit together.

I’ve done a word study on righteousness in the scriptures here. I found it’s possible for a word to have a general meaning, but also be employed in different contexts in specific ways. With respect to righteousness I found a series of inter-relationships. In particular the themes of Kingdom and Covenant are helpful in seeing how things fit together.

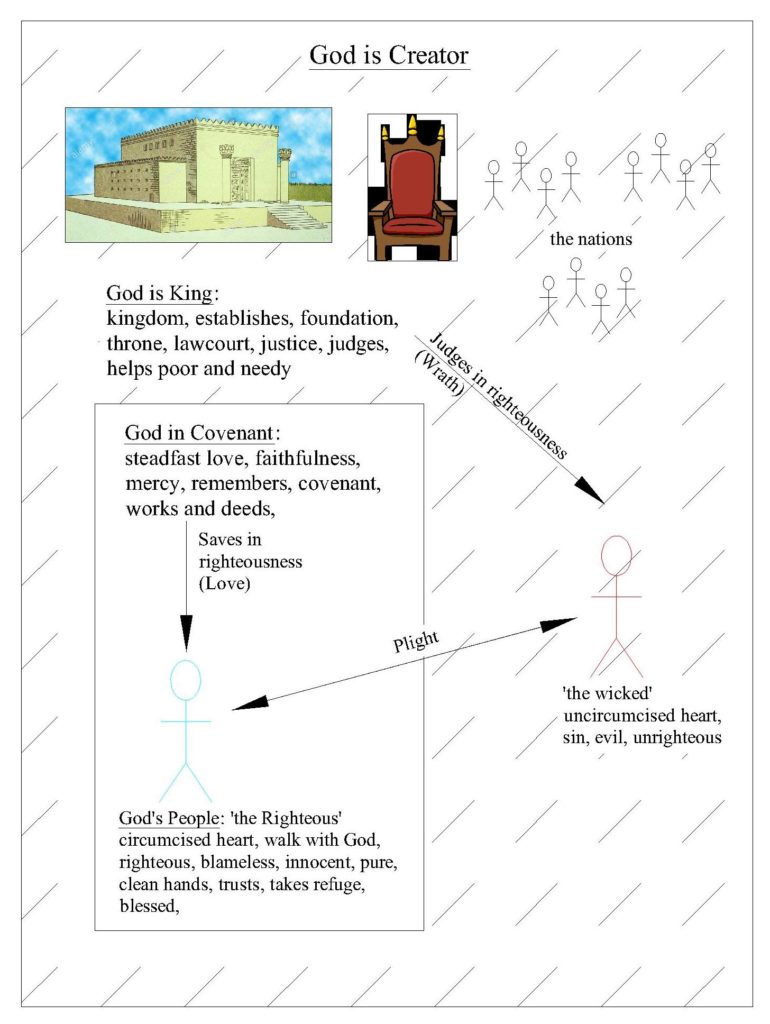

Kingdom and Covenant

When God is called ‘righteous’, he is sometimes acting as King, ruling over his kingdom. God is the righteous king of all creation. He sits on his throne and exercises his rule over his dominion. He executes justice by judging. When he judges He rewards the righteous for their righteousness and punishes the wicked for their sins. He rescues and saves those who take refuge in him and he helps the poor and needy.

When God is called ‘righteous’, he is sometimes acting in faithfulness to his covenant promises to Israel. God is in covenant with Israel. He has chosen Israel from all nations and given her the covenant law. The covenant law defines Israel’s ethics and those who keep the law are called ‘the righteous’. According to his steadfast love God saves the righteous from the wicked, from death and forgives their sin and iniquity. God is faithful to his covenant promises. When he fulfills his promises by bringing Israel into the promised land and when he curses Israel for disobedience he is being righteous according to his covenant obligations.

NT Wright rightly says,

NT Wright rightly says,

“For a reader of the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Jewish scriptures, ‘the righteousness of God’ would have one obvious meaning: God’s own faithfulness to his promises, to the covenant. God’s ‘righteousness’, especially in Isaiah 40-55, is that aspect of God’s character because of which he saves Israel, despite Israel’s perversity and lostness. God has made promises; Israel can trust those promises. God’s righteousness is thus cognate with his trustworthiness on the one hand, and Israel’s salvation on the other.” (p96, What Saint Paul Really Said)

Kingdom and Covenant. These are the most significant themes associated with God’s righteousness in the Old Testament. Law court themes are also mentioned but are quite rare when compared against these two.

I believe the themes of Kingdom and Covenant overlap, especially when salvation is concerned.

When Paul uses the expression ‘the righteousness of God’ its a good idea to recognise the Old Testament background of the expression and consider the immediate context to see which he is probably referring to.

It cant be said that the only reference to God’s righteousness is his covenant faithfulness. That being said in several cases where Paul uses the expression I think the NPP has a good grasp of what he means. In Romans 1-4 for example he refers to God’s promises, Abraham’s offspring, blessings, circumcision, and the law of Moses. This context should warrant consideration.

Justification

“It is important to note that not all Paul’s statements regarding justification are specifically linked with the theme of faith. The statements appear to fall into two general categories:

(1) those set in strongly theocentric contexts, referring to God’s cosmic and universal action in relation to human sin; and

(2) those making reference to faith, which is the mark to identify the people of God.

This is perhaps best regarded as a difference of emphasis rather than of substance. In its universal sense justification seems to underlie Paul’s argument for the universality of the gospel; there is no distinction between Jews and Gentiles.

But in its more restricted sense justification is concerned with the identity of the people of God, and the basis of its membership.” (p518, Ed. G.F. Hawthorne, R.P. Martin, D.G. Reid, Dictionary of Paul and His Letters;The IVP Bible Dictionary Series)

Imagery of Justification

1. COVENANT (Promises)

NPP is best known for associating justification with the covenant. If we understand justification within the imagery associated with covenant. Being justified is equivalent to being counted as a covenant member who has fulfilled his or her covenant obligations.

Remember ‘the righteous’ are those who adhere to the covenant law and come under the covenant blessings.

Rom 3.28,30,31 (‘law’); 4.3 (promises),6-8 (‘blessing’),9-11 (‘circumcision’),21-25 (‘promise’); 5.1 (‘peace’) use this kind of imagery.

9 Is this blessing then only for the circumcised, or also for the uncircumcised? For we say that faith was counted to Abraham as righteousness. 10 How then was it counted to him? Was it before or after he had been circumcised? It was not after, but before he was circumcised. 11 He received the sign of circumcision as a seal of the righteousness that he had by faith while he was still uncircumcised. The purpose was to make him the father of all who believe without being circumcised, so that righteousness would be counted to them as well, (Rom 4:9–11)

Circumcision was a sign of the covenant (Gen 17.11). Paul here associates the counting of righteousness here with covenant imagery. Those who are counted as righteous are considered to have fulfilled their covenant obligations and hence beneficiaries of the covenant blessings (e.g. salvation and forgiveness).

2. LAW COURT / FORENSIC (Judgment)

NPP is frequently accused of ignoring the law-court imagery associated with justification.

In conjunction with this the verb can be rendered and understood as ‘acquitted’. I think this is misleading. When a person is acquitted they are set free from a criminal charge by a verdict of not guilty. The focus is on the presence or absence of sin. While I recognise righteousness is commonly associated with innocence and blamelessness, the root of the verb for justification is actually dikai (right), not hamart (sin). Which means the legal process is not looking for sin, rather it looks for the practice of righteousness.

Neither is justification a ‘declaration’ as if to say God only justifies if He speaks. A persons right standing is often demonstrated publicly for example through deliverance from enemies (Ps 17.2; 35.23-24), the giving of a reward (1 Ki 8.32; cf. Rom 2.6-11) and resurrection (1 Tim 3.16; Rom 4.25; cf. Lk 14.14).

If we consider justification within law-court imagery we find it is the opposite of condemnation. When people are justified [considered to be righteous] they are then declared righteous and set upon a course towards eternal life. On the other hand, when God condemns someone they are judged as sinners and given a death sentence.

Rom 3.19-20 (‘accountable’); 5.16,18 (‘judgment’); 8.33-34 (‘charge’,’condemn’) and 1 Cor 4.3-4 (‘judged’,’court’) use this kind of imagery.

16 And the free gift is not like the result of that one man’s sin. For the judgment following one trespass brought condemnation, but the free gift following many trespasses brought justification. 17 For if, because of one man’s trespass, death reigned through that one man, much more will those who receive the abundance of grace and the free gift of righteousness reign in life through the one man Jesus Christ. (Rom 5:16–17)

3. SLAVE MARKET (Redemption, Liberation) / KINGDOM (Dominion, Reign)

Justification is also associated with the imagery of the slave market. Slaves are purchased and redeemed by their new master and king. They become part of his kingdom and serve him as his slaves and servants.

Our new master God is the one true King. He has justified his people from the dominion and slavery of Sin. We now serve him.

Rom 3.24 (‘redemption’); 6.6-9 (‘set free’) and Acts 13.37-39 (‘freed from everything’) use this kind of imagery.

6 We know that our old self was crucified with him in order that the body of sin might be brought to nothing, so that we would no longer be enslaved to sin. 7 For one who has died has been set free [justified] from sin. 8 Now if we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him. 9 We know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him. 10 For the death he died he died to sin, once for all, but the life he lives he lives to God. (Rom 6:6–10)

4. SACRIFICIAL (Blood, Death)

The final imagery associated with justification is that of the sacrificial system. The life blood and death of a sacrifice atones for sins, cleanses and makes a sinner, righteous. Jesus death on the cross justifies sinners. Rom 5.8-10 (‘blood’, death’); 5.19 (one mans obedience = death); Gal 2.21 (‘Christ died’) and Lk 18.13-14 (‘temple’, sacrifice) use this imagery.

6 For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly. 7 For one will scarcely die for a righteous person—though perhaps for a good person one would dare even to die— 8 but God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us. 9 Since, therefore, we have now been justified by his blood, much more shall we be saved by him from the wrath of God. (Rom 5:6–9)

I just associated four different kinds of imagery to do with justification (and thereby righteousness). Obviously, I don’t think righteousness fits into one kind of imagery because scripture doesn’t. In one book on Justification, Michael Bird relating justification to salvation critiqued Horton’s view (OPP) on justification saying,

The reason why Paul can switch between these images so freely is because no single image for salvation is hegemonic. They are all different ways of expressing the one reality of God’s acceptance of persons because of their faith in Jesus Christ. The various images of salvation are the contingent metaphors that attest to the coherent reality that God has acted dramatically in Christ for the deliverance of his people. (Bird, M. F. (2011). Progressive Reformed Response. In P. R. Eddy, J. K. Beilby, & S. E. Enderlein (Eds.), Justification: Five Views (p. 115). Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic.)

Events of Justification

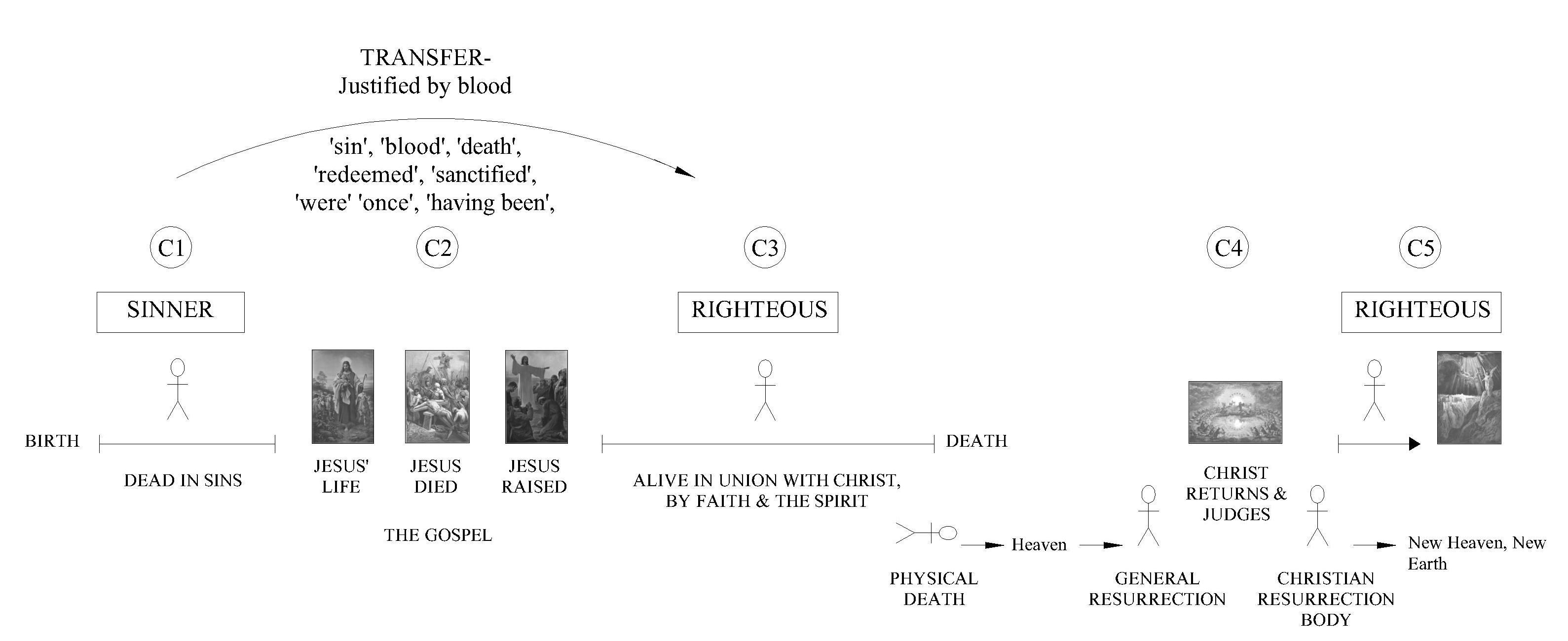

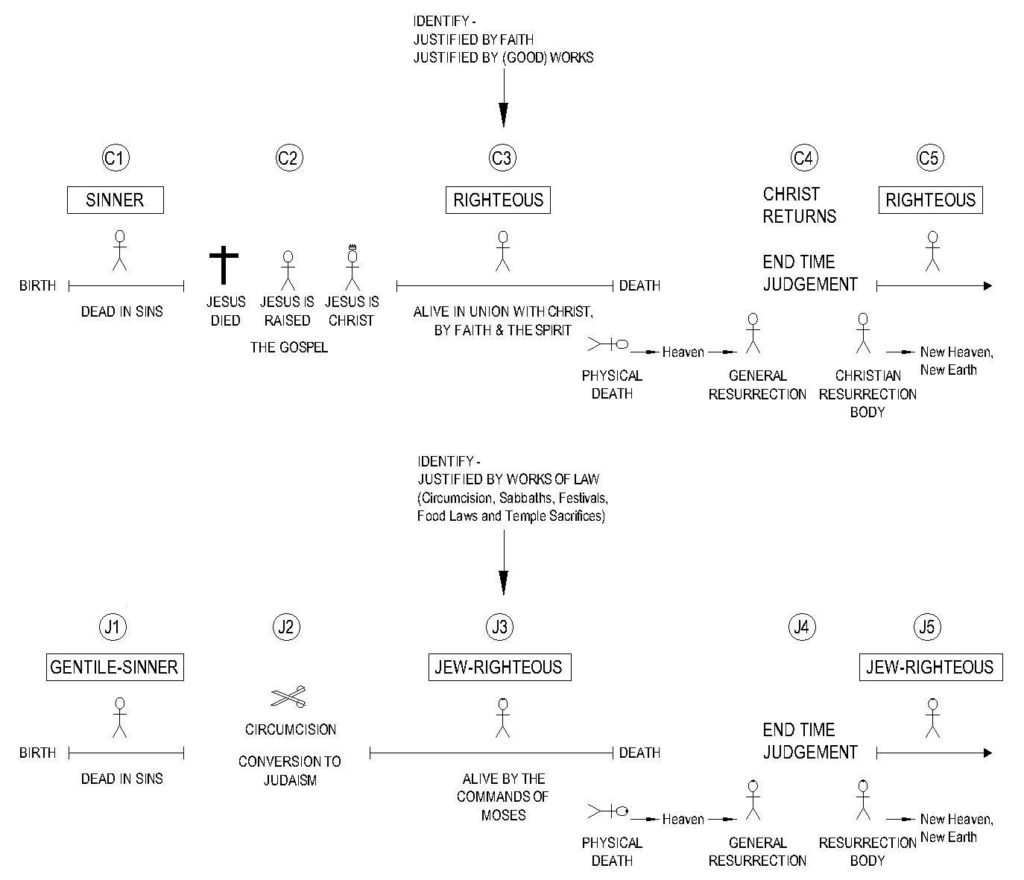

According to Paul, because of Adams fall all were made sinners (C1) and only some are justified (C2-C3), thereby being righteous in the sight of God.

19 For as by the one man’s disobedience the many were made sinners, so by the one man’s obedience the many will be made righteous. (Rom 5:19)

Paul here speaks of the first kind of event associated with justification.

1) Event @ C2 – Sinners are made righteous by the faithfulness of Jesus Christ (C1 to C3)

When the gospel (story of Jesus, proclaiming him as King) was proclaimed to a group of people and they believed Jesus is the risen Christ they were ‘justified’ in the sense they are made one of the righteous. Rom 5.1,9-10; 6.11,17; 1 Cor 6.11; Tit 3.7-8 look back to this moment from the C3 position which conferred:

When the gospel (story of Jesus, proclaiming him as King) was proclaimed to a group of people and they believed Jesus is the risen Christ they were ‘justified’ in the sense they are made one of the righteous. Rom 5.1,9-10; 6.11,17; 1 Cor 6.11; Tit 3.7-8 look back to this moment from the C3 position which conferred:

- a new relationship with God,

- a new expectation of behaviour and

- absence of continued sin.

In this event, when a sinner is justified, they become righteous in terms of their identity before God, their character and behaviour. They are now members of God’s covenant people and beneficiaries of his blessings and promises.

Justification involves internal and external transformation effected by the Holy Spirit.

Internally, the sinners heart is circumcised which enables it to believe Christ is the risen Lord (Rom 10.10; cf. 1 Cor 12.3) and trust God’s faithfulness to his promises (Rom 4.24-25). The sinners mind is opened to grasp and understand the gospel (1 Cor 2.10-16). Externally, the sinner is freed (slave market imagery) from the dominion and power of sin (Rom 6.7) through the redemption (slave market imagery) in Christ Jesus (union in Christ; Rom 3.24) and enters the dominion of grace and righteousness (Rom 6.15,18).

These Spiritual changes are coterminous with the covenant blessings of forgiveness / the non-imputation of sins received by those who believe irrespective of any works (of law) (Rom 4.6-8). These blessings of course are predicated on the respective understandings of incorporation and substitution associated with Christ’s blood spilling and death on the cross.

Consequently Paul expects believers to behave differently from the way they did before because they have been justified (1 Cor 6.9-11; Tit 3.7-8) and he expects God will do ‘much more’ for them now than when they were sinners (Rom 5.8-9).

The concepts of faith in Christ and the faithfulness of Christ are inseparable when people come to believe the gospel.

For Paul, ‘faith in Christ’ is more about believing Jesus is the risen Christ (e.g. Rom 4.17-24; 10.9), than how one can be forgiven (e.g. Rom 3.25).

The ‘faithfulness of Jesus Christ’ is mentioned in two significant ways. Incorporation and Substitution. Believers have been incorporated into Christ’ death and resurrection (Rom 3.22, Gal 2.20). Christ’s death on the cross was substitutionary. He died instead of us (Rom 5.8-9,16-19; 6.6-7; Gal 2.20).

Most believers in the New Testament were justified (C1 to C3) without ever hearing about justification because the message of the gospel doesn’t require it (e.g. 1 Cor 15.3-5; Acts 2.14-41; 10.27-44).

Once someone has believed the goal of the gospel (that Jesus is the risen Christ), that person receives the benefits of Christ’s atoning death and has become righteous, this next form of justification is possible.

This next concept is what the NPP affirms.

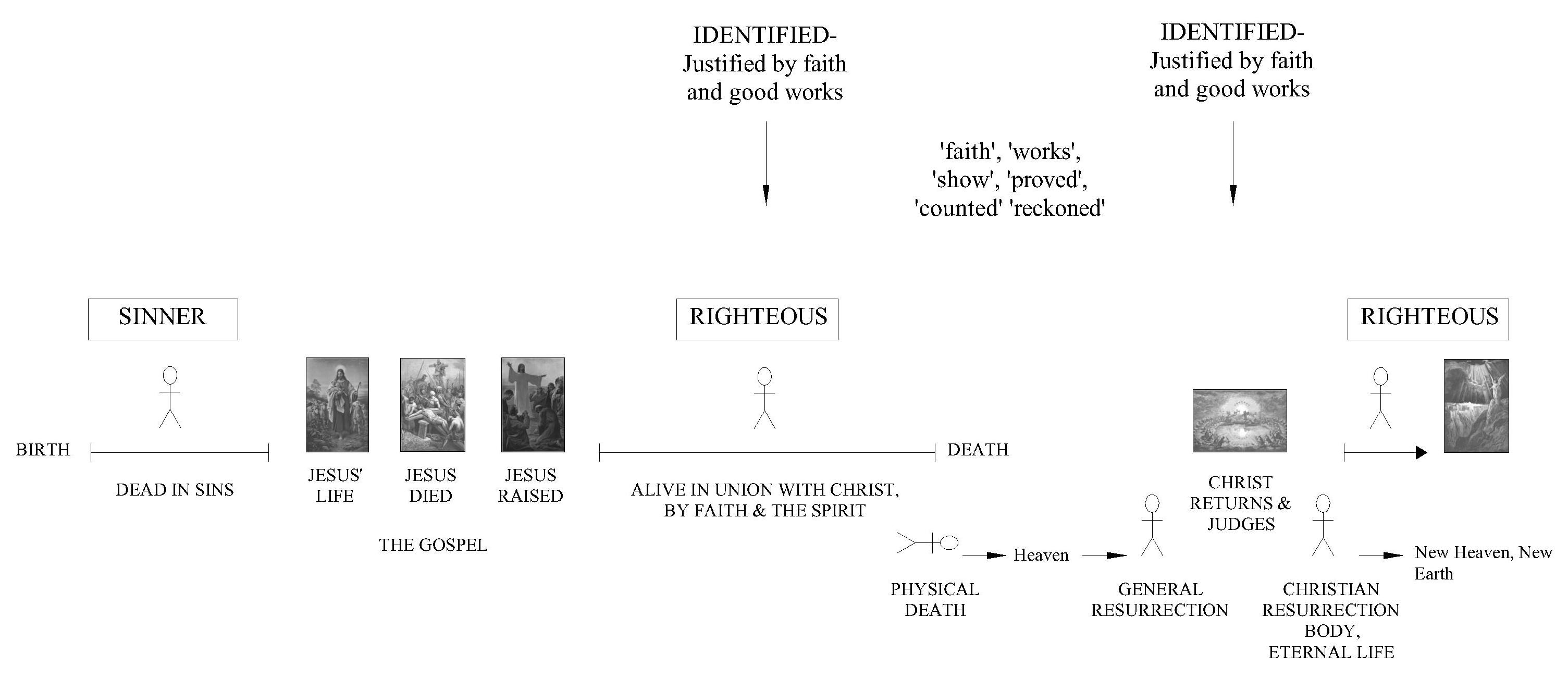

2) Event @ C3 – People are identified as righteous by their faith in Christ and good works (C3 or C4) In the New Testament there are two ways one can tell a person is righteous. By their faith in Christ (Rom 3.26,30; 10.10; Gal 2.16) and by their good works (Jas 2.21-25). Quite often this type of justification is within a lawcourt – forensic context.

In the New Testament there are two ways one can tell a person is righteous. By their faith in Christ (Rom 3.26,30; 10.10; Gal 2.16) and by their good works (Jas 2.21-25). Quite often this type of justification is within a lawcourt – forensic context.

Likewise God is justified (identified as righteous) when he is faithful to his promises and proved to be true (Rom 3.4).

Let God be true though every one were a liar, as it is written,

“That you [God] may be JUSTIFIED in your words [Promises], and prevail when you [God] are judged.” (Rom 3.4)

This form of justification is applied to people in the C3 and C4 categories. Faith can therefore be understood in two ways. First, faith is the gift of the Spirit that enables one to believe the gospel (Jesus rose from the dead and is Lord; Rom 5.1; 10.9-10). Second, faith is the key identifier for the newly created people of God.

Note: Paul is careful with his terms, but sometimes he compacts a lot into expressions. Sometimes he uses the shorthand ‘faith’ (e.g. Rom 3.25,28) to denote ‘faith in Jesus’ (e.g. Rom 3.26) just as he occasionally uses the shorthand ‘works’ (Rom 4.2) to denote ‘works of law’ (Rom 3.28). The key is to look at the immediate context to determine what he is referring to. Faith = Faith in Jesus, Works = Circumcision, Works of law.

Justified (identified as righteous) + works of law = ‘boundary marker’ for the Jews.

The Jews believed observance of the works of law identified the righteous. Or in other words, those who were meeting the covenant obligations of the law of Moses. Identification of the righteous is a justification issue because ‘justified’ is also a verb which denotes how you can tell a person is righteous (Jas 2.21-24).

Observance of the works of law is a moral and a social issue.

When Gentiles heard the gospel and came to believe in Jesus. The Jews thought these Gentiles were sinning by neglecting the works of law. Hence they denied they were righteous in God’s sight and refused to be in fellowship with them. Non Torah observant Gentiles were unclean (e.g. Acts 10.28).

When Paul made this point to Jews he was making an ecclesiological and a soteriological point. That is, he is defining the new criteria Jewish believers should use to determine who is righteous (Identity, Character and Behaviour). They believed those who observed the works of law were the righteous in God’s sight.

Justified (identified as righteous) + faith in Jesus = ‘boundary marker’ for the Christians.

Paul’s answer in response to the Jews was no – those who believe Jesus is the Christ are righteous.

The statement,

‘a person is not justified by works of law but through faith in Jesus Christ’ (Gal 2.16)

means God does not identify a person as righteous by their observance of works of law [only Jews], but through faith in Jesus Christ [Jewish and Gentile believers].

This in effect includes Gentile believers in the group known as ‘the righteous’ and removes the moral requirement to observe the ‘works of law’. Neglecting to observe God’s moral commands known as the ‘works of law’ is no longer a sin in Paul’s eyes.

Remember I quoted from Justin Martyr when writing about the law of Moses? In response to Trypho’s issue, Justin eventually replies;

‘For if one should wish to ask you why, since Enoch, Noah with his sons, and all others in similar circumstances, who neither were circumcised nor kept the Sabbath, pleased God, God demanded by other leaders, and by the giving of the law after the lapse of so many generations, that those who lived between the times of Abraham and of Moses be justified by circumcision, and that those who lived after Moses be justified by circumcision and the other ordinances—to wit, the Sabbath, and sacrifices, and libations, and offerings; [God will be slandered] unless you show, as I have already said, that God who foreknew was aware that your nation would deserve expulsion from Jerusalem, and that none would be permitted to enter into it. (For you are not distinguished in any other way than by the fleshly circumcision, as I remarked previously.

For Abraham was declared by God to be righteous, not on account of circumcision, but on account of faith. For before he was circumcised the following statement was made regarding him: ‘Abraham believed God, and it was accounted unto him for righteousness.’ (Gen 15.6; cf Rom 4.3,5,6,9,11,24; Gal 3.6)

And we, therefore, in the uncircumcision of our flesh, believing God through Christ, and having that circumcision which is of advantage to us who have acquired it—namely, that of the heart—we hope to appear righteous before and well-pleasing to God’ Justin Martyr. (1885). Dialogue of Justin with Trypho, a Jew. In A. Roberts, J. Donaldson, & A. C. Coxe (Eds.), The Ante-Nicene Fathers: The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus (Vol. 1, p. 245). Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company.

The additional implication Paul makes to the Jews is that it is not a moral requirement for anyone to observe the works of law (e.g. Rom 14.1-23).

Believing Jews should therefore not break fellowship with believing Gentiles even though they don’t observe the works of law. Note that Paul does insist believers should break fellowship with those who claim to be brothers if they persist in sin (1 Cor 5.9-13). What links justification to fellowship is how one defines sin.

James by way of comparison says, ‘a person is justified by works and not by faith alone.’ (Jas 2.24) In some instances Paul’s uses the same word translated as ‘justified’ as James does (dikaioutai, Gal 2.16=Gal 3.11=Jas 2.24; edikaiōthē, Rom 4.2=Jas 2.21,25). The key difference between both expressions is not how they view ‘justified’. Rather it is that Paul’s understanding of ‘works of law’ (the commands in the Jewish law that require actions) is different from James’ ‘works’ (helping the poor). James says the righteous are identified by their good works and not by their faith alone.

James is not arguing you can tell who the righteous are by their observance of circumcision, sabbath and holidays, sacrificial laws and purity and washings. Paul is not arguing that helping the poor or doing good works will jeopardize a believer’s salvation.

3) Event @ C4 – The final judgment is a rendering according to works

“Justification according to works is entirely biblical (e.g. Rom 14:10; 2 Cor 5:10), and the question is, how do righteousness by faith and judgment according to works relate to each other? The solution I think is to closely observe the prepositions that Paul uses.

Paul consistently employs dia (“through”) and ek (“by/from”) to indicate that faith is the instrument by which believers are justified (Rom 3:22, 25; 5:1; Gal 2:16).

But he uses kata (“according to”) when it comes to the role of works at the final judgment (Rom 2:6; 2 Cor 11:15). The works, faithfulness, obedience and life of the believer must accord with God’s verdict at the final judgment. Thus, justification is on the basis of faith, while judgment is congruent with the life of obedience.

(Bird, M. F. (2011). Progressive Reformed View. In P. R. Eddy, J. K. Beilby, & S. E. Enderlein (Eds.), Justification: Five Views (p. 154). Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic.)

There are a large number of passages which complicate our understanding of the final judgment and salvation.

The NPP acknowledges grace and forgiveness are part of what happens at conversion and throughout a believers life. Then looking toward the final judgment it affirms all people will be judged according to their works.

Regarding judgment the scriptures say:

- God and Christ make the judgement (Mt 7.21-23; 1 Cor 11.32; 2 Cor 5.9-10; Rom 14.10-12; Mt 25.31-46),

- God’s judgement will be impartial (Rom 2.6-11; Eph 6.5-9; Col 3.22-25; 1 Pet 1.14-19),

- God’s judgement will divide people into the righteous and sinners (Mt 7.17-20; 12.33-37; 13.47-50; 25.31-46)

- God’s judgement will divide people according to their fruit / deeds (Mt 16.24-28; 25.31-46; Jn 5.25-29; Rom 2.6-11; 2 Cor 5.9-10; Gal 5.16-26; Gal 6.7-10)

Regarding the righteous the scriptures say:

- The righteous will have produced good fruit (Mt 3.8-10; 7.21-23; Lk 10.25-28; Heb 12.14)

- The righteous will have served the Lord according to their ability (Mt 25.14-30,31-46; Eph 6.5-9)

- The righteous will be a product of the Lords work (Rom 14.4,20)

- The righteous inherit the Kingdom (Mt 13.38-43; Rom 2.6-11)

Regarding sinners the scriptures say:

- Sinners will have produced bad fruit and sin (Mt 5.21-22,29-30; 7.21-23; 18.7-9; 1 Cor 6.9-10; 1 Thes 4.6; Heb 10.26-31)

- Sinners are removed from God’s presence (Mt 13.38-43,47-50; 25.14-30; 25.31-46)

For a more detailed explanation of how these work together see my page on Future Judgment and Salvation.

NT Wright has been criticised by the OPP reformers for believing these texts. He answers those who criticise him by repeating the same thing several times.

“I did not write Romans 2; Paul did. …

Nor did I write Romans 14.10-12: …

Nor did I write 2 Corinthians 5.10”

He then quotes a series of other passages. Most of which I’ve listed above. Wright then says;

“There is simply far too much of this material for it all to be swept aside.” (ibid)

Mistakes made about Justification

Ever heard of the Covenant of Works? The classical reformed doctrine of justification (OPP) affirms the imputation of the active obedience of Christ. The basic idea is that when someone exercises faith in Christ, there is a transfer of Christ’s ethical righteousness onto them. Such that when they are judged in the future God sees Christ’s perfect righteousness and not their sin. Consequently God will declare them righteous.

Carson, Grudem, Horton, Piper are advocates of this view and in part it drives their criticism of Wright. Witsius and Brakel give an outline of the doctrine if your interested. Rom 4.3-4, 2 Cor 5.21 and Phil 3.8-9 are the main verses used to promote the doctrine. I’ve written what I believe to be better interpretations of each (Rom 4.3-4; 2 Cor 5.21 and Phil 3.8-9).

Importantly, John Owen recognises this as an inner reformed debate.

(2.) There hath been a controversy more directly stated among some learned divines of the Reformed churches (for the Lutherans are unanimous on the one side), about the righteousness of Christ that is said to be imputed unto us. For some would have this to be only his suffering of death, and the satisfaction which he made for sin thereby, and others include therein the obedience of his life also. (See http://www.puritanlibrary.com/ Volume 5 of 21 (on Justification). page 63)

Its not a OPP vs. NPP debate. Its a reformed vs. reformed debate.

Robert H. Gundry wrote a famous article titled ‘Why I Didn’t Endorse The Gospel of Jesus Christ: An Evangelical Celebration’ highlighting this point.

NPP advocates like Wright reject this doctrine as unbiblical. The main reason why is because there is no explicit text in the scriptures which teaches it.

Otherwise see these articles.

In fact there are texts which contradict it. These are Heb 10.12-14; Rom 5.18-19; and Rom 8.2-4 (includes the role of the Spirit). They each clearly state the death of Christ is the necessary and sufficient cause for a sinner being made right in the sight of God. Christ’s obedience, while necessary to maintain a sacrifice without blemish, is not needed to be transferred to the believer for God to consider them as righteous.

This ends my introduction. I hope you found it helpful understanding some of the New Perspectives main points. I’ll finish with this video.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2015. All Rights Reserved.