Paul in the twentieth century, then, has been used and abused much as in the first. Can we, as the century draws towards its close, listen a bit more closely to him? Can we somehow repent of the ways we have mishandled him and respect his own way of doing things a bit more?

This book is an attempt to do just that: to stand back from the ways we have read Paul and to explore a bit more how Paul himself suggests we read him. It is an attempt to study Paul in his own terms. It is trying to come to grips with what he really said. (Loc 338)

- Link: Amazon

- Length: 194

- Difficulty: Medium-Easy

- Topic: Pauline Theology

- Audience: Mainstream Christians

Most pew sitters of protestant congregations I assume will never have been exposed to the amount of scholarship presented in this small and readable book. This is the book that made the new perspective on Paul known to everyday Christians.

NT Wright is an internationally recognised scholar who joins together the disciplines of Historical research and Biblical Theology. This is his short and controversial book on Paul.

In this review I summarize the main points of each of his chapters. In some cases interacting with some arguments leveled against him.

This post is one of my book reviews.

(Note: My quotations are from the ebook so please excuse my location references).

Contents

1 – Puzzling Over Paul

Pauline scholarship is a battleground of different schools of thought. Notably the Reformed, New Perspective, Apocalyptic and Jewish. Wright begins by running through a series of twentieth century readings of Paul.

Schweitzer questions what the ‘centre’ of Paul’s thought is. Is it ‘justification by faith’ or perhaps ‘Union in Christ’ or something else altogether? Schweitzer argues Paul was a Jewish thinker. Importantly for Wright’s discussion he tried to answer four questions.

- Where do we put Paul in the history of first-century religion? (HISTORY)

- How do we understand his theology, its starting point and centre? (THEOLOGY)

- How do we read the individual letters, getting out of them what Paul himself put into them? (EXEGESIS)

- And, what is the pay-off, the result, in terms of our own life and work today? (APPLICATION) (Loc 165)

Wright to varying degrees assesses a series of contemporary scholars on these same questions.

Bultmann was an existentialist. He argued Paul was a (Greek) Hellenist thinker. His argument was that Paul’s dominant focus was an analysis of the human plight and the decision of faith to escape it.

Davies did an early study in Paul and Rabbinic Judaism. Part of this was motivated by a new post second world war attitude to Judaism.

Kasemann is with Schweitzer arguing that Paul resembled apocalyptic Judaism. With Bultmann concerning justification, legalism and pride. For him, Paul presents a critique of Judaism from within Judaism.

Sanders was a student of Davies. Wrote the famous book Paul and Palestinian Judaism which I have reviewed here. He argued Judaism was not a religion of legalism and works righteousness as mistakenly believed by many protestants. He advocated a position called ‘Covenantal Nomism’, the response to God’s election and rescue from slavery.

Wright answers the four questions himself briefly.

Regarding history he says now a days almost all scholars regard Paul as a very Jewish thinker. Regarding theology he says there is no agreement on the centre of Paul’s theology. Regarding exegesis he says vast amounts of secondary literature is taken into account but not enough major theological statements. Regarding application he says there is a lot of old style ‘preaching of the gospel’ highlighting sin and pride, finding their answer in the cross. He thinks we should confronting today’s neo-pagans just as Paul confronted his.

2 – Saul the Persecutor, Paul the Convert

Wright introduces Paul by telling his story. He was a Pharisee who persecuted the church (Rom 10.2; Phil 3.6; Gal 1.13-14; 1 Cor 15.9). But which type of Pharisee? Was he a member of Hillel, the ‘lenient’ one, or Shammai the ‘strict’ one? Paul was in the Shammai sect. He would have been exposed to many intra Jewish debates of his time and been fiercely loyal to his group. The Shammai were strict in regards to Torah observance because they had a deep concern for the Israel, the people, the land and the temple.

He locates Saul in his historical context explaining his worldview.

Saul, like a great many Jews of his day, read the Jewish Bible not least as a story in search of an ending; and he conceived of his own task as being to bring that ending about. The story ran like this. Israel had been called to be the covenant people of the creator God, to be the light that would lighten the dark world, the people through whom God would undo the sin of Adam and its effects.

But Israel had become sinful, and as a result had gone into exile, away from her own land. Although she had returned geographically from her exile, the real exilic condition was not yet finished. The promises had not yet been fulfilled. The Temple had not yet been rebuilt. The Messiah had not yet come. The pagans had not yet been reduced to submission, nor had they begun to make pilgrimages to Zion to learn Torah. Israel was still deeply compromised and sinful.

Into this situation, the scriptures spoke clearly and powerfully of the time that would surely come when all these things would be put right. (Loc 459)

Wright briefly discusses how Jews like Paul would frame the concept of justification. He says justification would be associated with the Hebrew law court, the covenant and eschatology. Giving us a taste for what will come in chapter seven he says the final justification could be anticipated under certain circumstances by certain means.

He then moves on to Saul’s conversion and its immediate significance. Wright sets this event in the context of what the Jews believed about what would happen in the end times. They believed everyone would be raised from the dead.

On the Damascus road Paul had a vision of the risen Jesus. The significance of seeing Jesus raised from the dead implies the ‘one true God had done for Jesus of Nazareth, in the middle of time, what Saul had thought he was going to do for Israel at the end of time’.

This event gave Saul an entirely new perspective.

3 – Herald of the King

Wright argues for Paul conversion and vocation were inseparable. He was called (which is arguably the closest theological concept relating to conversion) to be an apostle to the Gentiles to proclaim the risen king Jesus.

Paul’s vocation was to tell that the crucified Jesus of Nazareth had been raised from the dead by Israel’s God; that he had thereby been vindicated as Israel’s Messiah and he was therefore the Lord of the whole world.

This story, the true story of Israel’s God and his people, the true story (in consequence) of the creator and the cosmos. And his calling was to tell it to the whole world. (Loc 615)

This of course is gospel ministry. Now more controversially for evangelicals of the reformed persuasion.

The word ‘gospel’ and the phrase ‘the gospel’ have come to denote, especially in certain circles within the church, something that in older theology would be called an ordo salutis, an order of salvation.

‘The gospel’ is supposed to be a description of how people get saved; of the theological mechanism whereby, in some people’s language, Christ takes our sin and we his righteousness; in other people’s language, Jesus becomes my personal saviour; in other languages again, I admit my sin, believe that he died for me, and commit my life to him. In many church circles, if you hear something like that, people will say that ‘the gospel’ has been preached. …

In the present case, I am perfectly comfortable with what people normally mean when they say ‘the gospel’. I just don’t think it is what Paul means. In other words, I am not denying that the usual meanings are things that people ought to say, to preach about, to believe. I simply wouldn’t use the word ‘gospel’ to denote those things. (Loc 630f)

Before drumming out his explanation of the gospel, Wright covers some of the Background to Paul’s usage. The two backgrounds for Paul’s use of the Greek word euangelion (‘gospel’) and euangelizesthai (‘to preach the gospel’) are the:

- Hebrew scriptures, and the

- Pagan (Greco-Roman) usage.

Isaiah (Isa 40.9; 52.7) proclaimed the good news predicting the return of Israel from exile. The Romans gave an announcement of a great victory, or to the birth, or accession, of an emperor.

Using Romans 1:1-5 Wright explains the fourfold gospel concerning Jesus:

God’s gospel concerning his Son is a message about God –the one true God, the God who inspired the prophets –consisting in a message about Jesus.

[God’s gospel is] a story –

A true story – about a human life, death and resurrection through which the living God becomes king of the world.

A message which had grasped Paul and, through his work, would mushroom out to all the nations. That is Paul’s shorthand summary of what ‘the gospel’ actually is.

It is not, then, a system of how people get saved. The announcement of the gospel results in people being saved – Paul says as much a few verses later.

But ‘the gospel’ itself, strictly speaking, is the narrative proclamation of King Jesus. (Loc 716)

Get that? He says the gospel is: the story about Jesus, that proclaims him King, and results in people being saved. Wright is making a significant distinction here, distinguishing between narrative and salvation. You might have missed the significance unless he rubbed the typical reformed evangelical nose in it by saying ‘it is not a system of how people get saved’.

Wright will later on say about Rom 1.16-17;

When Paul says ‘the gospel’, he does not mean ‘justification by faith’;

he means the message, the royal announcement, of Jesus Christ as Lord. Romans 1:3-4, as we saw, gives a summary of the content of his gospel; Romans 1:16-17 gives a summary of the effect, not the content, of the gospel. (Loc 2212)

This particular definition rubbed against John Piper so he wrote the book Future of Justification in response. However both Scot McKnight and John Dickson (the links are my reviews) are clearly in strong agreement. See also my series on What is the gospel? and the Early Church on the Gospel.

Wright then goes in to unpack in detail the fourfold significance of the (1) crucified and (2) risen (3) King Jesus (4) according to the scriptures.

4 – Paul and Jesus

Essentially in this chapter Wright gives his Trinitarian credentials. He approaches the issue however demonstrating Paul was a Jewish monotheist, but redefined it with Jesus and the Spirit within (1099).

Wright first explains a few of the essential elements of first-century Jewish Monotheism.

Jewish monotheism in this period was not an inner analysis of the being of the one true God. It was not an attempt at describing numerically what this God is, so to speak, on the inside. Instead, it made two claims, both of them polemical in their historical context. (Loc 1069)

These claims are:

- There is only one God, the God of Israel,

- God is creator of the world and is active in his world.

Then he shows Jesus within Paul’s Jewish Monotheism, working through a series of passages. Here are a couple and what you want to consider is how Paul modifies a typical monotheistic OT passage and specifically builds Jesus Christ into it.

| Jewish Monotheism | Jewish Monotheism with Jesus within |

| 4 “Hear, O Israel:

The LORD our God, the LORD is one. 5 You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might. (Dt 6.4-5) |

6 yet for us there is

one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist. (1 Cor 8.6) |

| 22 “Turn to me and be saved, all the ends of the earth! For I am God, and there is no other. 23 By myself I have sworn; from my mouth has gone out in righteousness a word that shall not return:

‘To me every knee shall bow, every tongue shall swear allegiance.’ (Isa 45.22-23) |

9 Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, 10 so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, 11 and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father. (Phil 2.9-11) |

Wright then shows the Spirit within Paul’s Jewish monotheism in a similar manner. Firstly he looks at Galatians 4.1-7 and notes the underlying narrative echoes of the exodus in Paul’s construction. Israel in slavery in Egypt, rescued from slavery, guided by the pillar of cloud and fire and led into the promised land.

(Note: These arguments could be used in discussions with non-Trinitarians such as Jehovah’s Witnesses and introducing not yet Christians to how we get the notion of Trinity.)

Wright notes in particular the respective roles of the Father, Son and Spirit in the narrative.

The closer we get to his own terms, the more we discover that his view of God is trinitarian. It is emphatically not tritheist; there is only one God, as for Jewish monotheism. It is emphatically not pantheist; this God is not identified with the world. It is emphatically not Deist; this God is not distant or detached, but closely involved with the world. It is emphatically not modalist; the three are really distinct, since the middle term is the human being Jesus, who prayed to the Father as Father, and who, for Paul, is no longer physically present in the same way as once he was. (1275)

One significant feature of Wright’s theology present in his discussion of Galatians (and I found particularly in his Paul and the Faithfulness of God) that I find both a strength and weakness is that a lot of the time he operates at a very deep level of Paul’s thought, sometimes not interacting with the surface level issues.

| What the text says | Most theologians |

| What Paul wants to achieve with his audience | Most theologians |

| Paul’s theology (how he thinks) | NT Wright |

| Paul’s worldview | NT Wright |

This doesn’t mean he is necessarily wrong, rather often he is simply speaking about different things than other people are when they consider the text. Wright generally considers big picture issues, other exegetes perhaps the textual details.

5 – Good News for the Pagans

Wright begins this chapter outlining his proposal for how Paul interacted with pagans and Jews with respect to his revised Jewish monotheism of Christ and Spirit. A lot of his points I found a bit pie in the sky.

The basic features of paganism were deeply engrained in the lives and habits of ordinary people. Sacrifice, holy days, oracles, inspection of auspices, mystery-cults, and a good deal else besides were part of the daily world of Paul’s audience. (Loc 1489)

Paul’s central beliefs thus naturally generated a mission in which polemical engagement was of the essence. He did not have to make the Jewish message into an essentially Gentile message for it to be audible or comprehensible to his pagan hearers (Contra contextualisation?); … What the Gentiles needed was precisely the Jewish message, or rather the Jewish message as fulfilled in Jesus the Messiah. (Loc 1426)

Paul offered the reality of the true God, and the creation as his handiwork. It follows from this that Paul’s preaching challenged the pagan religions. He challenged the worldly institutions at the level of political power, particularly of empire. In his teachings and his example he set out a way of being human which undercut the ways of being human on offer within paganism. Paul told the true story of the world in opposition to pagan mythology. Finally, he opposed the pagan philosophies of his day.

At the conclusion of the chapter Wright is prepared to talk about justification by faith. This is where he starts dropping bombs on traditional reformed theology.

Paul continued to believe, as Saul had done, that one could tell, in the present, who was a member of the true people of God.

For Saul, the badge was Torah: those who kept Torah strictly in the present were marked out as the future true Israel. For Paul, however, that method would only intensify the great gulf between Jew and Gentile, which the death and resurrection of the Messiah had obliterated.

Rather, now that the great act had already occurred, the way you could tell in the present who belonged to the true people of God was quite simply faith: faith in the God who sent his Son to die and rise again for the sake of the whole world.

This is the point at which, as we shall see in the next two chapters, the doctrine of ‘justification by faith’ becomes crucially relevant in Paul’s mission to the pagan world. It was not the message he would announce on the street to the puzzled pagans of (say) Corinth; it was not the main thrust of his evangelistic message.

It [the doctrine of justification by faith] was the thing his converts most needed to know in order to be assured that they really were part of God’s people. (Loc 1629)

6 – Good News for Israel

Wright begins this chapter explaining how the first century readers of the Septuagint would have understood Paul’s expression ‘the righteousness of God’. He builds together the themes of Covenant, Law court and Eschatology. About covenant he says;

For a reader of the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Jewish scriptures, ‘the righteousness of God’ would have one obvious meaning: God’s own faithfulness to his promises, to the covenant. God’s ‘righteousness’, especially in Isaiah 40–55, is that aspect of God’s character because of which he saves Israel, despite Israel’s perversity and lostness. God has made promises; Israel can trust those promises. God’s righteousness is thus cognate with his trustworthiness on the one hand, and Israel’s salvation on the other. (Loc 1672)

He then explains the imagery of the Hebrew law court. He describes the role of the judge and what it means for him to be righteous in the Hebrew law court.

Applied to the judge, it means (as is clear from the Old Testament) that the judge must try the case according to the law; that he must be impartial; that he must punish sin as it deserves; and that he must support and uphold those who are defenceless and who have no-one but him to plead their cause. (Loc 1703)

He explains the role of the defendant and what it means for him to be righteous.

If and when the court upholds the plaintiff’s accusation, he or she is ‘righteous’. This doesn’t necessarily mean that he or she is good, morally upright or virtuous; it simply means that in this case the court has vindicated him or her in the charge they have brought. (Ibid)

Contra the classical reformed doctrine of double imputation he says;

If we use the language of the law court, it makes no sense whatever to say that the judge imputes, imparts, bequeaths, conveys or otherwise transfers his righteousness to either the plaintiff or the defendant. Righteousness is not an object, a substance or a gas which can be passed across the courtroom. (Loc 1718)

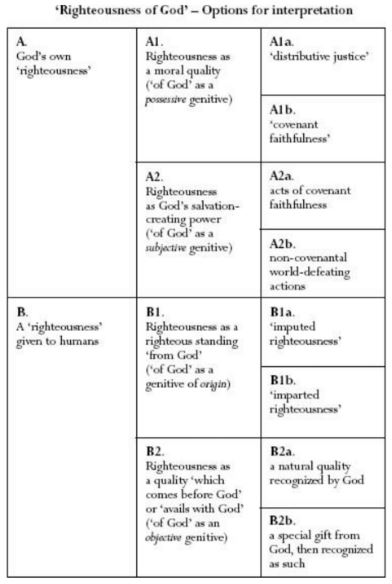

Wright works through various ways of interpreting ‘the righteousness of God’. See the table above. He clearly advocates it as God’s covenant faithfulness and goes against Luther’s definition.

Wright works through various ways of interpreting ‘the righteousness of God’. See the table above. He clearly advocates it as God’s covenant faithfulness and goes against Luther’s definition.

I’ve written a series on righteousness here.

Understandably the reformed criticize him for not siding with the tradition Luther set up.

However, I think Wright is right in this context because of the proximity to salvation. That is, a core reason why God saves is because he has promised to do so as part of his covenant. Covenant and salvation cannot be easily separated.

However given this, in other passages particularly in the OT, as my series indicates, I generally define God’s righteousness in the scriptures relating to his rule as king.

Wright proceeds to review several of Paul’s letters arguing his interpretation makes better sense of what Paul is saying. I’ve written several posts on these myself (Philippians, 2 Corinthians and Romans).

7 – Justification and the Church

In this chapter Wright corrects the popular merit theology understanding of ‘justification by faith’. He argues it does not do justice to the richness and precision of Paul’s doctrine and distorts it at various points.

In answering the question ‘What is Justification?’ Wright begins by reminding us of Sanders work, successfully undermining the typical protestant understanding of first century Judaism. He also highlights some of his disagreement with Sanders as well.

The discussions of justification in much of the history of the church, certainly since Augustine, got off on the wrong foot – at least in terms of understanding Paul – and they have stayed there ever since. … Classically, this doctrine ever since Augustine has been concerned with warding off some version or other of the Pelagian heresy. (Loc 1992f)

He disagrees with the common interpretation that justification denotes the event or process where a person becomes right with God.

I disagree with Wright with respect to some passages (see my series here) but agree in the passages he has in mind (see my series here). Wright should have limited his statements to ‘justification by faith’ as Stendahl did. See my review of Stendahl’s book here.

Wright’s understanding of justification, as is his interpretation of the ‘righteousness of God’ revolves around the concepts of Covenant, Law court and Eschatology. Once again he draws our attention again to the first century Jewish context and worldview.

[Covenant] ‘The purpose of the covenant was never simply that the creator wanted to have Israel as a special people, irrespective of the fate of the rest of the world. The covenant was there to deal with the sin, and bring about the salvation, of the world.’ (Loc 2063)

[Law court] ‘God himself was seen as the judge; evildoers (i.e. the Gentiles, and renegade Jews) would finally be judged and punished; God’s faithful people (i.e. Israel, or at least the true Israelites) would be vindicated.’ (Loc 2076)

[Eschatology] ‘Their redemption, which would take the physical and concrete form of political liberation, the restoration of the Temple, and ultimately of resurrection itself, would be seen as the great law-court showdown, the great victory before the great judge.’ (Loc 2076)

[Anticipation] ‘this event could be anticipated under certain circumstances, so that particular Jews and/or groups of Jews could see themselves as the true Israel in advance of the day when everyone else would see them thus as well. Those who adhered in the proper way to the ancestral covenant charter, the Torah, were assured in the present that they were the people who would be vindicated in the future.’ (Loc 2076)

Now he turns to Paul and what his doctrine of justification look like when the first century Jewish view is revised in light of Jesus death and resurrection and the work of the Spirit. He works through several of Paul’s writings starting with Galatians and moves on to discuss Corinthians, Philippians and Romans.

Despite a long tradition to the contrary, the problem Paul addresses in Galatians is not the question of how precisely someone becomes a Christian, or attains to a relationship with God. The problem he addresses is: should his ex-pagan converts be circumcised or not? … On anyone’s reading, but especially within its first-century context, it has to do quite obviously with the question of how you define the people of God: are they to be defined by the badges of Jewish race, or in some other way? (Loc 2104)

What Paul means by justification, in this context, should therefore be clear. It is not ‘how you become a Christian’, so much as ‘how you can tell who is a member of the covenant family’. When two people share Christian faith, says Paul, they can share table-fellowship, no matter what their ancestry. (Loc 2143)

[Covenant] Within this context, ‘justification’, as seen in 3:24-26, means that those who believe in Jesus Christ are declared to be members of the true covenant family; which of course means that their sins are forgiven, since that was the purpose of the covenant.

[Law court] They are given the status of being ‘righteous’ in the metaphorical law court.

[Eschatology, anticipation] When this is cashed out in terms of the underlying covenantal theme, it means that they are declared, in the present, to be what they will be seen to be in the future, namely the true people of God. Present justification declares, on the basis of faith, what future justification will affirm publicly (according to Rom 2:14-16 and Rom 8:9-11) on the basis of the entire life. (Loc 2281)

A few comments. He regards faith in Christ as the means by which God identifies members of the covenant. With this in mind justification is a declaration of covenant membership. Let me address several points arising from this.

Firstly he speaks of righteousness as covenant membership. From my study on righteousness I can verify there are definitely covenantal (link) and corporate membership (link) overtones associated with righteousness in addition to the normal moral (link) overtones. Therefore I sympathize with his claim. However I refrain from simply equating righteousness with covenant membership, it’s broader than that.

Secondly in relation to faith. Wright says it’s how one can tell who is righteous in God’s sight (Jews-Gentiles, identification). The typical reformed understanding is that it is how a sinner becomes righteous in God’s sight (Sinners, instrumental).

I’ve addressed this in my new perspective page. Basically it’s both. When sinners hear the gospel, faith is instrumental and they become right with God. Then as Jews or Gentile believers their faith in Christ continues to be instrumental but also is seen as evidence of the Spirit’s work and therefore the means by which one can tell they are right with God. Paul’s justification by faith expression has the Jew-Gentile believer context in mind and Paul is explaining how one can tell who is righteous in multi-ethnic communities.

28 For we hold that one is justified by faith apart from works of the law. 29 Or is God the God of Jews only? Is he not the God of Gentiles also? Yes, of Gentiles also, 30 since God is one—who will justify the circumcised by faith and the uncircumcised through faith. (Rom 3.28-30)

14 But when I saw that their conduct was not in step with the truth of the gospel, I said to Cephas before them all, “If you, though a Jew, live like a Gentile and not like a Jew, how can you force the Gentiles to live like Jews?” 15 We ourselves are Jews by birth and not Gentile sinners; 16 yet we know that a person is not justified by works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ, so we also have believed in Christ Jesus, in order to be justified by faith in Christ and not by works of the law, because by works of the law no one will be justified. (Gal 2.14-16)

Regarding his statement, ‘what future justification will affirm publicly on the basis of the entire life’ again we have a major debate on the role of works in the future judgment.

See my reviews on:

- Stanley, Wilkin, Schreiner, Dunn, Barber, Four Views on the Role of Works at the Final Judgment, and

- Stanley, A., Salvation Is More Complicated than You Think, and

- Sandlin, P.A., A Faith That Is Never Alone, and

- Rainbow, Paul., The Way of Salvation: The Role of Christian Obedience in Justification).

In my opinion Wright is simply saying what Paul does here, although he does get in trouble for using the word ‘basis’. I’ve posted on future judgment and salvation to demonstrate the future judgment is indeed according to works here.

8 – God’s Renewed Humanity

In this chapter Wright concentrates on Paul’s vision of God’s renewed humanity.

Paul articulated, in other words, a way of being human which he saw as the true way. In his ethical teaching, in his community development, and above all in his theology and practice of new life through dying and rising with Christ, he zealously articulated, modelled, inculcated, and urged upon his converts a way of life which he saw as being the genuinely human way of life. (Loc 2391)

At the center of Paul’s vision of genuine humanity is the true worship of the one true God. Wright considers the theme of worship in Galatians, Corinthians, Thessalonians and Romans.

The end and goal of God’s renewed humanity is resurrection. Wright argues resurrection involves transforming the present mode of physicality into a new mode of which Jesus in his risen body is our only glimpse of what will happen. (Loc 2472f)

Paul sees holiness as something which necessarily characterizes all those who are renewed in Christ. He recognizes Christians still struggle with sin. Throughout Paul’s writings, genuine holiness is seen in terms of dying and rising with Christ. (Loc 2519f)

Regarding mission Wright says ‘the doctrine of the image of God in his human creatures was never the belief simply that humans were meant to reflect God back to God. They were meant to reflect God out into the world.’ (2627) Wright then goes on to explain the importance of gospel ministry and summoning people to the obedience of faith.

9 – Paul’s Gospel Then and Now

Wright’s begins this chapter reviewing his earlier arguments on the gospel and justification.

For Paul, ‘the gospel’ creates the church; ‘justification’ defines it. The gospel announcement carries its own power to save people, and to dethrone the idols to which they had been bound. ‘The gospel’ itself is neither a system of thought, nor a set of techniques for making people Christians; it is the personal announcement of the person of Jesus. That is why it creates the church, the people who believe that Jesus is Lord and that God raised him from the dead.

‘Justification’ is then the doctrine which declares that whoever believes that gospel, and wherever and whenever they believe it, those people are truly members of his family, no matter where they came from, what colour their skin may be, whatever else might distinguish them from each other.

The gospel itself creates the church; justification continually reminds the church that it is the people created by the gospel and the gospel alone, and that it must live on that basis. (Loc 2670)

In this chapter Wright summarizes the main points of his book. He reviews again what the main scholarly schools of thought on Paul are. He talks about the gospel proclamation of Jesus as king and Lord. He talks about justification and it’s implications for how we view church and community. He raises the important point that people can be justified without even knowing it. People are justified by faith in Jesus, not justified by faith in the doctrine of justification by faith. He reviews again what Paul means by the righteousness of God.

10 – Paul, Jesus and Christian

In this last chapter Wright spends a lot of time sparring with AN Wilson on his understanding of Paul. He addresses his treatment of Saul’s background, Judaism and Hellenism, the Cross and resurrection and finally Jesus and God. He’s not a big fan.

He ends up discussing whether Jesus was the founder of Christianity or if Paul was. To finish up my summary of his book Wright says;

Jesus believed it was his vocation to bring Israel’s history to its climax. Paul believed that Jesus had succeeded in that aim. Paul believed, in consequence of that belief and as part of his own special vocation, that he was himself now called to announce to the whole world that Israel’s history had been brought to its climax in that way. When Paul announced ‘the gospel’ to the Gentile world, therefore, he was deliberately and consciously implementing the achievement of Jesus. (Loc 3221)

Recommendation

Most pew sitters of protestant congregations I assume will never have been exposed to the amount of scholarship presented in this small and readable book.

This is the book that made the new perspective on Paul known to everyday Christians.

His comments on the gospel and Paul’s understanding of justification are of immense importance for his we interpret Galatians and Romans. Indeed lots of Paul’s writings.

I recommend this book for widespread reading. In my opinion Wright has hit the nail on the head regarding the historical truth of the gospel and justification by faith.

I’ve found after much study on the early church, his understandings reflect what they believed regarding the gospel and justification by faith. That is Wright is not giving a new perspective, he is actually articulating the early perspective on Paul. What he says about the gospel and justification by faith are not new at all.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2017. All Rights Reserved.