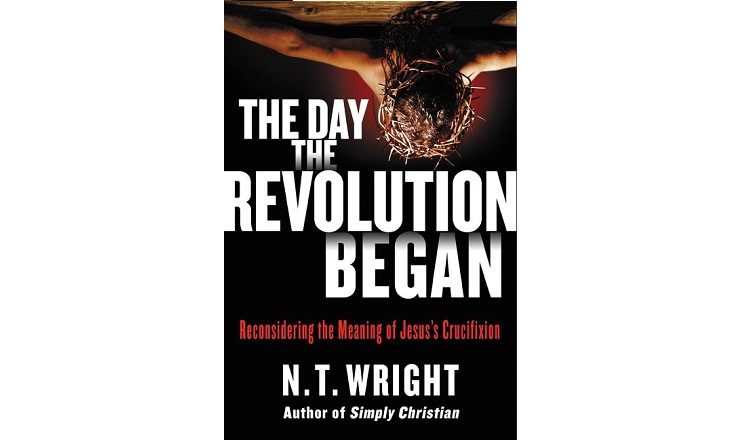

This book is NT Wright’s narrative theology applied to the doctrine of the atonement. It is comparable to John Stotts, Cross of Christ in some respects with the key difference that Wright favours the Christus Victor understanding of the Cross. That being said, Wright does attempt to incorporate penal substitution and propitiation into his view.

This book is NT Wright’s narrative theology applied to the doctrine of the atonement. It is comparable to John Stotts, Cross of Christ in some respects with the key difference that Wright favours the Christus Victor understanding of the Cross. That being said, Wright does attempt to incorporate penal substitution and propitiation into his view.

- Link: Amazon

- Length: 448 pages

- Difficulty: Medium

- Topic: Atonement

- Audience: Educated Christians

- Published: 2016

This is the first of a few books I have shortlisted to do some research on the atonement so I can at least have some idea of what is going on in recent debates. I’m broadly familiar with some of the key texts that can be employed in describing the atonement. The passages are well known:

- The Passover (Ex 12; Dt 16),

- Levitical Sacrifices (Lev 1-6),

- Day of Atonement (Lev 16),

- Isaiah’s Suffering Servant (Isa 53) and

- scattered New Testament references (e.g. Mk 10.45; Rom 3.25; Gal 3.13; 1 Pet 3.18; 1 Jn 2.2; Heb 10; Rev 5.9-10).

The big questions for me are:

- How do Jesus (before) and the Apostles (after) primarily understand the atoning significance of the Cross, and

- Given there are multiple images / understandings of the Cross, do they work together and if so how?

Overall I believe Wright answers these questions.

I listened to this book rather than read it. Consequently my understanding of it won’t be as detailed as my normal reads. The book is relatively dense. But overall I feel I can give a big picture review of the book.

This post is one of my book reviews.

Contents

- PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

- 1. A Vitally Important Scandal Why the Cross?

- 2. Wrestling with the Cross, Then and Now

- 3. The Cross in Its First-Century Setting

- PART TWO: “IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE BIBLE”: THE STORIES OF ISRAEL

- 4. The Covenant of Vocation

- 5. “In All the Scriptures”

- 6. The Divine Presence and the Forgiveness of Sins

- 7. Suffering, Redemption, and Love

- PART THREE: THE REVOLUTIONARY RESCUE

- 8. New Goal, New Humanity

- 9. Jesus’s Special Passover

- 10. The Story of the Rescue

- 11. Paul and the Cross (Apart from Romans)

- 12. The Death of Jesus in Paul’s Letter to the Romans (The New Exodus)

- 13. The Death of Jesus in Paul’s Letter to the Romans (Passover and Atonement)

- PART FOUR: THE REVOLUTION CONTINUES

- 14. Passover People

- 15. The Powers and the Power of Love

Overview

The introductory chapters of the book demonstrate Wrights wide knowledge of multiple historical, classic and contemporary issues and how they are at times associated with the cross. Personally I was impressed with the breadth of his knowledge of the world and its history.

Almost from the start Wright brings out his favourite whipping boy. The popular evangelical doctrine of atonement.

Laying all that out would be a task for another time, and I shall try to avoid getting tangled up in all this by referring to the view I am opposing as the “works contract.” The “works contract” functions in the popular mind like this.

God told his human creatures to keep a moral code; their continuing life in the Garden of Eden depended on their keeping that code perfectly. Failure would incur the punishment of death. This was then repeated in the case of Israel with a sharpened-up moral code, Mosaic law. The result was the same.

Humans were therefore heading for hell rather than heaven.

Finally, however, Jesus obeyed this moral law perfectly and in his death paid the penalty on behalf of the rest of the human race. The overarching arrangement (the “works contract”) between God and humans remained the same, but Jesus had done what was required.

Those who avail themselves of this achievement by believing in him and so benefiting from his accomplishment go to heaven, where they enjoy eternal fellowship with God; those who don’t, don’t. (74-5)

Wright will allude to this works contract through the whole book. In particular, the expression ‘works contract’ appears 45 times and the expression ‘go to heaven’, 37 times. Many times he will compare the depiction of God taking out his wrath by killing his own child as outright paganism. A few times is okay, but after listening to the book, I found it quite repetitive and increasingly annoying as I worked through. In my opinion such repetition takes away from the value of the book.

At times Wright will argue for some sort of biblical understanding and claim this is commonly ignored or underplayed by those of the reformed persuasion. He is occasionally taken to task about this by those wanting to recommend the reformers to their audiences. I think it is helpful to realise Wright is criticising reformed belief at the popular level. If one mined the reformers, et al, one is sure to find some references to these topics (because many have commented on the whole body of scripture). Its another question to ask if it is their dominant focus or what the reformers are best known for.

Covenant of Vocation

Wright really begins his argument for the book in Part Two. Most of the book can be understood to approach the scripture using a broadly thematic approach. Wright is not listing a whole bunch of scripture and working out the best way to understand it. Rather, presumably having done this work, he is explaining his finished understanding in a logical fashion.

Wright if anything is a narrative theologian. Consequently he starts from Genesis 1, where he introduces the biblical alternative to the covenant of works. The covenant of vocation.

The vocation in question is that of being a genuine human being, with genuinely human tasks to perform as part of the Creator’s purpose for his world. The main task of this vocation is “image-bearing,” reflecting the Creator’s wise stewardship into the world and reflecting the praises of all creation back to its maker. Those who do so are the “royal priesthood,” the “kingdom of priests,” the people who are called to stand at the dangerous but exhilarating point where heaven and earth meet. (75)

Using this as his starting point, Wright then describes the human plight with sin through this lense.

The diagnosis of the human plight is then not simply that humans have broken God’s moral law, offending and insulting the Creator, whose image they bear—though that is true as well.

This lawbreaking is a symptom of a much more serious disease. Morality is important, but it isn’t the whole story.

Called to responsibility and authority within and over the creation, humans have turned their vocation upside down, giving worship and allegiance to forces and powers within creation itself. The name for this is idolatry. The result is slavery and finally death. (76)

Thus sin is largely understood in terms of handing over our allegiance from God to idols. Idolatry. I can see a lot of reformed folks agreeing with this. The big point here is that Wright’s framing of sin primarily concerns idolatry and slavery. This will bear itself out in Wrights primary understanding of the work of the cross.

In Accordance with the Bible

Wright approaches the Old Testament background to atonement by focussing on the gospel statement in 1 Cor 15.3: Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, or ‘the Bible’ as he renders Gk. γραφάς Trans. graphas. Through the statement ‘in accordance with the bible’, Wright will seek to draw in the overarching narrative of the OT leading and pointing to Christ’s death.

Wright approaches the Old Testament background to atonement by focussing on the gospel statement in 1 Cor 15.3: Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, or ‘the Bible’ as he renders Gk. γραφάς Trans. graphas. Through the statement ‘in accordance with the bible’, Wright will seek to draw in the overarching narrative of the OT leading and pointing to Christ’s death.

When the early Christian formula says that Jesus’s death happened “in accordance with the Bible,” it really does mean, as Jesus himself indicated in Luke 24, that the single great narrative had now come forward to its long-awaited goal. Somehow, Israel’s sins must be dealt with so that the project of global restoration—including dealing with the sins of the world in general—can go forward.

The larger biblical narrative indicated that the fate of humankind as a whole was hanging upon the rescue operation that had been launched in the family of Abraham, but that was now itself, it seemed, in peril. (105)

In my opinion, ‘in accordance with the scriptures’ is a bit ambiguous. Generally I’ve referred it to God’s promises in the OT fulfilled in Christ (e.g. here and here). I have a specific focus on God’s promises. I’ve seen some refer specifically to OT atonement texts in a more limited form. According to Campbell, The Gospel in Christian Traditions (review), the early church arguing the God of the Gospel is the same as that of the OT and Israel, was keen to establish the continuity of the Gospel events and their faith with that in the OT. Wright here likewise associates it with the whole biblical narrative.

Forgiveness of Sins

From the above quote, Wright will then go on to write;

What was then required, in both the focused personal sense and the national and cosmic sense, was the “forgiveness of sins.” This would take the form of the real return from exile, which would have its full effect not only in Israel, but in the whole world. (105)

This is quite an important definition for understanding the rest of the book. Wright will continue to refer to the expression ‘forgiveness of sins’. I thought at times his use of the expression a bit ambiguous. Is he referring to corporate or individual forgiveness? From here we can see Wright has both in mind. But he has a distinct emphasis on corporate forgiveness (e.g. Lk 1.77), akin to Israel’s return from exile and the new Passover. In the typical evangelical church however this expression is more commonly interpreted as individual forgiveness (e.g. Lk 5.20), more along the lines of acquittal, canceling of debt (‘I forgive you’). Wright does not often distinguish the two.

Of course Wright, wouldn’t be Wright if he didn’t draw in his understanding of exile. Prior to the above statement he says;

If, therefore, exile is eventually undone—whatever precisely that will mean—this will be both a “forgiveness of sins” and a new life the other side of death—and the restoration of the life-giving divine Presence. (103)

Thus he highlights he is focussing on both the plight and condition before forgiveness and the cross, and the new life afterward. In general, Wright give more emphasis on what happens after the cross, not the plight before. He could not be accused of miserable sinner Christianity, which suits me just fine as I think this is popular under-realised eschatology applied to anthropology.

The Revolutionary Rescue

Part three of the book turns to the New Testament. Wright begins saying most contemporary scholarship on the atonement seems to ignore the Gospels, with the exception of a single passage – Mk 10.45. At times echoing similar themes to those he brings up in How God Became King (Amazon), Wright concentrates on the Passover, the Kingdom of God and Jesus’ victory over the evil powers. This understanding them becomes the lense through which Paul and other NT writers are interpreted.

Part three of the book turns to the New Testament. Wright begins saying most contemporary scholarship on the atonement seems to ignore the Gospels, with the exception of a single passage – Mk 10.45. At times echoing similar themes to those he brings up in How God Became King (Amazon), Wright concentrates on the Passover, the Kingdom of God and Jesus’ victory over the evil powers. This understanding them becomes the lense through which Paul and other NT writers are interpreted.

Passover

Wright ties in Jesus’ understanding of the passover with that of Israel’s passover, his exile theology and the broad narrative of the Old Testament.

Wright ties in Jesus’ understanding of the passover with that of Israel’s passover, his exile theology and the broad narrative of the Old Testament.

I therefore regard it as a fixed point in understanding Jesus’s death that Jesus himself understood what was about to happen to him in connection with Israel’s ancient Passover tradition and that this was linked directly to his beliefs about the launch of God’s kingdom. The royal power of God had already been displayed, close up and dramatically, in his public career. But Jesus believed that through his death this royal power would win the decisive victory through which not just Israel but also the whole world would be liberated: ransomed, healed, restored, forgiven. (182)

One point to note is that Wright often attempts to enter Jesus’ own mindset when describing his actions, often tying them to OT prophesies. With respect to the cross he frequently ties Jesus’ awareness of his own vocation and his đeath to the servant songs in Isaiah. While this is hard to prove, its both plausible and I think edifying to reflect on Jesus’ motivations.

Kingdom of God

Luke’s account of the Passover directly connects Passover, and thus Christ’s death, with the kingdom of God. Two themes not easy to integrate. Luke writes;

Luke’s account of the Passover directly connects Passover, and thus Christ’s death, with the kingdom of God. Two themes not easy to integrate. Luke writes;

14 And when the hour came, he reclined at table, and the apostles with him. 15 And he said to them, “I have earnestly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer. 16 For I tell you I will not eat it until it is fulfilled in the kingdom of God.” 17 And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he said, “Take this, and divide it among yourselves. 18 For I tell you that from now on I will not drink of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes.” (Lk 22:14–18)

Wright connects kingdom and cross writing;

This is how the cross establishes God’s kingdom: by bearing and so removing the weight of sin and death. The kingdom of God is established by destroying the power of idolatry, and idols get their power because humans, in sinning, give it to them. Deal with sin, and the idols are reduced to a tawdry heap of rubble. Deal with sin, and the world will glorify God. (256)

Understanding sin as idolatry, connects the atonement, how God resolves the problem of sin with the concepts of reigning powers (kingdom of God, evil powers of this world). This is the Christus victor model of the atonement. Wrights language leans more on expiation (dealing with sin, cleansing, purifying, blotting out) rather than propitiation (dealing with wrath, punishment). (A topic Wright will deal with in greater detail in his section on Paul.) His understanding I felt conveyed a transformative (healing) understanding of the cross as well.

Victory over the Powers

The power of the rulers has been broken—the new Passover, to use our earlier language, has now taken place for certain—because in the messianic events “God made us alive together with Jesus, forgiving us all our offenses.” Victory over the powers, once more, is accomplished through the forgiveness of sins. (269)

This may suggest Wright is predicating victory over the powers on forgiveness of sin. Wrights explanation depicts sin and idolatry as a prison, the evil powers the jailers. Then forgiveness unlocks the prison, so the prisoners can go free and escape, thus defeating the evil powers that control those in prison. What we see here is the interrelation of biblical imagery pertaining to forgiveness and atonement.

Opposing Views

At points through the book, Wright challenges various understandings of the atonement and associated interpretations of scripture. Some, as already mentioned include propitiation (which he says is close to pagan belief), double imputation – including 2 Cor 5.21 (which he ought rejects), the ‘Romans Road’ interpretation of Romans 1-4 (which he challenges drawing heavily on the Jews vocation as teacher in Rom 2) and penal substitutionary atonement.

At points through the book, Wright challenges various understandings of the atonement and associated interpretations of scripture. Some, as already mentioned include propitiation (which he says is close to pagan belief), double imputation – including 2 Cor 5.21 (which he ought rejects), the ‘Romans Road’ interpretation of Romans 1-4 (which he challenges drawing heavily on the Jews vocation as teacher in Rom 2) and penal substitutionary atonement.

Wright actually agrees with substitutionary atonement, however for him the framing narrative is critical to understand it properly. Commenting on a popular misconception of Gal 3.1-14 he writes;

But this form of “penal substitution” has little or nothing to do with the narrative in which that theory is normally found. That narrative says the oblique language of the scripture passages being quoted is just a roundabout way of saying, “We sinned, God punished Jesus, and we are all right again.” That narrative says that in Deuteronomy Israel is a mere example of humans being given a moral challenge, failing it, and needing to be rescued. Those are just attempts to smuggle a “works contract” into this passage—and doing so results in distortion of every line.

This passage is about the “covenant of vocation,” here specifically Israel’s vocation, the seed-of-Abraham vocation, to be the means of blessing for the world. The curse has been borne; the blessing can now flow to the nations; and Jews themselves, the “we” at the end of the verse, can now receive the sure sign of covenant renewal, the down payment on the full “inheritance,” namely, the Spirit.

Galatians 3:1–14 thus focuses on the achievement of the cross in undoing the Deuteronomic “curse of exile.” This passage makes it clear that this happens through the representative work of the Messiah, who, because he is Israel’s representative, can therefore appropriately act as substitute. (239-40)

Recommendation

I found the book reasonably dense because of the number of issues addressed and how he approaches scripture (broad sweeps rather than specialised study of select passages). This is probably a strength and a weakness. Sometimes I felt his system of interpretation ran roughshod over the texts.

As mentioned before his reference to ‘go to heaven’ and ‘works contract’ became quite tedious and repetitive. It would probably be less noticeable reading the book rather than listening to it.

On reflection the book is ordered well, making later reference and searches not too difficult.

Wrights view however provides an overarching view of the atonement that seems to me to have plausible explanatory power with respect to integrating the scriptural narrative, God’s covenant promises, forgiveness of sins, the kingdom of God and substitution. I quite liked how he integrated the kingdom of God with the cross. I found it quite helpful for later reference how he addressed common evangelical misconceptions of scripture.

Overall, I recommend this book as a great example of NT Wright’s erudition and well argued defense of an overarching Christus Victor model of atonement.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2019. All Rights Reserved.