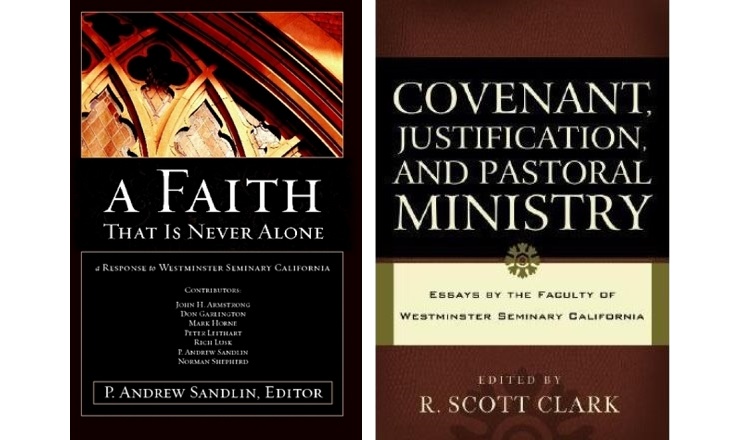

‘A Faith That Is Never Alone’ (hereafter ‘FNA’) is a series of essays written by a group of reformed scholars in response to another book ‘Covenant, Justification, and Pastoral Ministry: Essays by the Faculty of Westminster Seminary California’ (Amazon link) (hereafter ‘CJPM’) written by the Faculty of Westminster Seminary California.

‘A Faith That Is Never Alone’ (hereafter ‘FNA’) is a series of essays written by a group of reformed scholars in response to another book ‘Covenant, Justification, and Pastoral Ministry: Essays by the Faculty of Westminster Seminary California’ (Amazon link) (hereafter ‘CJPM’) written by the Faculty of Westminster Seminary California.

The book gives an in depth look into intra-reformed debates surrounding the role of repentance and obedience in faith, justification, Imputation and Union in Christ, John Calvin’s theology and the Covenant of Works, Law and Gospel, and The New Perspective on Paul.

- Link: Amazon

- Length: 400

- Difficulty: Heavy-Medium Academic

- Topic: Systematic Theology, Faith and Works

- Audience: Educated Christians

- Published: 2007

‘In some circles today, when anyone seeks to explore a new idea or restate an old one in new words, there is an immediate rush to judgment [condemnation]. Often this approach amounts to theological bullying and oppression, leading to a situation where scholars do not feel free to go where they believe God through his Word is leading them, for fear that they will be declared heretics before they have even had time to explore the matter properly.’ (A.T.B. McGowan, editor, Always Reforming: Explorations in Systematic Theology)

The reoccurring theme throughout the book is what role repentance and obedience play in gospel ministry, justifying faith and the process of salvation.

After I first read this book several years ago I read Calvin’s Institute’s shortly after. I found it quite helpfully focused my attention on Calvin’s understanding of the interrelationship between faith, obedience and salvation.

The book covers a great deal of nuanced systematic theology concepts associated (to my thinking) with the reformed explanatory system. This book has been a helpful stepping stone for me.

Now, I feel I have I’ve moved on from some the viewpoints espoused. Not that I disagree, rather that I am no longer convinced any reformed explanatory system adequately captures the bible’s frameworks, concepts and language. But it has been good to reread the book and refresh my understanding of Calvinist theology.

The authors of FNA seem to embrace a generous and wide understanding of reformed theology. The authors of CJPM on the other hand seem to have a narrow and divisive understanding of reformed theology. I imagine the authors of CJPM might be the kind of people who would argue John Piper is not reformed (link).

This post is one of my book reviews.

Contents

Background

The editor of CJPM is Robert Scott Clark. He is an American Reformed pastor and seminary professor. Clark teaches at Westminster Seminary California, and I suspect he instigated the book recruiting other faculty members of his Seminary.

The editor of CJPM is Robert Scott Clark. He is an American Reformed pastor and seminary professor. Clark teaches at Westminster Seminary California, and I suspect he instigated the book recruiting other faculty members of his Seminary.

Clark says CJPM mainly aims to address the claims and proponents of the Federal Vision within Reformed circles and/or those in Reformed circles influenced by the New Perspective on Paul, especially with respect to Justification.

Here is one review of the book.

I don’t know what to think about the seminary if they felt they needed to team up like this and argue against these men. They seem like theological police. But then again, this is not uncommon with those who like to pride themselves on their ‘reformed’ doctrine.

I don’t know what to think about the seminary if they felt they needed to team up like this and argue against these men. They seem like theological police. But then again, this is not uncommon with those who like to pride themselves on their ‘reformed’ doctrine.

Andrew Sandlin is the editor of FNA. He is President of the Center for Cultural Leadership and Preaching Pastor at Cornerstone Bible Church-Santa Cruz County. Here are the contributors of FNA and who they are responding to.

| Chapter | A Faith that is Never Alone | Responding to Covenant, Justification, and Pastoral Ministry |

| 1 | John H. Armstrong | Hywel R. Jones |

| 2 | Norman Shepherd | W. Robert Godfrey, David VanDrunen |

| 3 | Mark Horne | Michael S. Horton |

| 4 | Rich Lusk | Scott Clark, David VanDrunen |

| 5 | Peter Leithart | Michael S. Horton (Estelle) |

| 6 | Andrew Sandlin | Scott Clark, Michael S. Horton |

| 7 | Norman Shepherd | Scott Clark |

| 8 | Don Garlington | S. M. Baugh |

| 9 | Rich Lusk | – |

| 10 | Don Garlington | I. M. Duguid |

Glossary

I figure I should ‘have a go’ at giving basic glossary of concepts this book will draw upon. I don’t have time to do much research or link where I’m getting it from, so please excuse the ‘off the top of my head’ explanations.

Gospel

Unless noted otherwise, I largely assume both sides hold to various forms of the ‘soterian’ gospel. By that I mean something resembling Gilbert’s gospel (What is the gospel?):

- God the Righteous Creator

- Man the Sinner

- Jesus Christ the Saviour

- Response – Faith and Repentance

According to this view, the content of the gospel message is shaped by expressing the problem the audience has with their sin, it’s just punishment and the solution provided by trusting in Christ’s sin atoning death. This gospel is about ‘how can a person be saved?’ And gives two possible answers. Earning God’s favour by good works? Or trusting in Jesus’ death alone?’ This soterian gospel can be and is regularly reduced to ‘justification by faith’ coming from a reformed reading of Romans 1-3.

(Note: Based on my numerous writings on the gospel, I differ from this understanding.)

Repentance

Occasionally the gospel message is accompanied with a call to repent.

I’ve written a word study on the concept. Basically repentance involves turning away from sin and turning to God. Repenting also involves grieving over sin and giving it up to live God’s way. Those who repent are expected to bear good fruit in keeping with repentance.

(Note: Repentance involves actually doing something. The question, ‘Does a person have to repent to be saved?’ may cause concern for those holding to the ‘faith alone’ notion of the soterian gospel.)

Righteousness

Righteousness is usually defined in biblical dictionaries as ‘conformity to a standard or norm’. In the scriptures the term is often associated with innocence, uprightness and blamelessness. Therefore ethics and morality.

For many reformed, ‘righteousness’ is often assumed to mean ‘sinless perfection’ or ‘perfect obedience’ because the focus is on a divine – human comparison. Of righteousness before God. This particular understanding of what it means to be righteous is foundational to reformed theology.

(Note: In my view the scriptures frequently refer to individuals as ‘righteous’. The divine – human comparison associated with perfect obedience is rarely in view when the term is used. Some noted exceptions are Job 25.2-6; Ps 143.1-3. See also Mt 7.11.

Righteousness involves the concepts of identity (God’s people), character and behavior. Ongoing practice of righteousness is required (1 Jn 3.7) and the righteous are blameless before God (cf. Phil 3.6). I think all the righteous (even before Moses) are beneficiaries of God’s covenant promises (cf. Heb 11). In the scriptures the righteous are typically saved by God from various plights and are beneficiaries of God’s covenant promises, including inheriting God’s kingdom (cf. 1 Cor 6.9; Eph 5.5; Gal 5.21 – note the interrelationship between the unrighteous and inheritance. Inheriting is typically a benefit of those who are in the covenant).

Zechariah and his wife were ‘righteous before God’ (Lk 1.6). Contrary to the reformed understanding of what it means to be righteous before God. I don’t think this passage implies they were sinlessly perfect or had perfect obedience at the time. I think being righteous before God, as their culture would have understood Luke, held in tension the regular practice of righteousness, which is the primary emphasis and forgiveness of occasional sins.

Righteousness of God

Carrying forward the last point the righteousness of God is another long debated topic. Does it refer to God’s character or his actions? Maybe a mixture of both?

The righteousness of God can be understood in terms of his ethical character. Sometimes it is understood within the imagery of the law court (forensic) and is a status that can be passed around.

The righteousness of God could refer to the exercise of God’s rule over creation. In this scheme it is associated with His holy justice. Because God is holy he must punish sin and reward good. Consequently judgment and salvation can be seen as outworkings of God’s righteousness.

Sometimes it is associated with God’s faithfulness to his covenant promises. This is exemplified in the gospel, the life, death and resurrection of Jesus by which God fulfills his promises of salvation to his covenant people.

Some say the righteousness of God is also transformative. When the gospel is proclaimed, declaring the righteousness of God it transforms its listeners such that they grow in maturity and obedience.

(Note: I’ve written a bit of stuff on justification in my New Perspective page).

Justification

The classic Roman Catholic doctrine of justification is both declaration and process. By the infusion of God’s being into a sinner, that person is made righteous and from then onwards they grow in righteousness by cooperating with God’s grace.

The classic Protestant doctrine of justification holds that the declaration and process are distinct and inseparable. Justification is only the forensic (law-court) declaration of righteousness made over a sinner. (Progressive) Sanctification is the (never in this lifetime completed) process where a sinner grows in maturity and obedience.

Both of these are working with an understanding that righteousness is ethical in nature. Hence justification is a declaration made about a person’s moral status before God. If a person is declared righteous (remember – perfect obedience) they are set on a course towards life. If they are guilty of sin (i.e. a sinner), they are condemned and given a death sentence.

The New Perspective on Paul is well known to push the covenantal understanding into justification as well. Instead of being a declaration of a person’s moral or ethical status. In this case it is a declaration of covenant membership. The covenant of course is the basis for a person’s forgiveness, salvation and inheritance.

Justification can be divided up into Initial Justification and Final Judgment. Quite often justification (‘dik’ word group) and judgment (‘kri’ word group) are seen as the same thing. Consequently statements like ‘justified by faith’ and ‘judgment according to deeds’ can be seen as contradictory.

(Note: I’ve written a bit of stuff on justification in my New Perspective page.

My opinion following from my comments above on righteousness before God and contra reformed doctrine, is that I do not think justification is the declaration a sinner is sinlessly perfect or perfectly obedient. Justification in my mind can be either when a sinner becomes righteous or when someone who is righteous is identified as such.)

Sanctification

In reformed circles, the concept of sanctification is usually associated with (the never completed) growth in godly character and maturity. From the perspective of sin:

- a believer is first freed from the penalty of sin,

- then during their lifetime gradually freed from the power of sin and

- finally when Jesus returns the presence of sin is removed from them entirely.

Sanctification is typically associated with the second process.

If you did a word search on sanctification in the New Testament and study it you will see it is generally not associated with a process. Rather it refers to a definitive event whereby the believer in some way is made holy and set apart for God when they are converted. However some argue for its usage as a process by showing the concept of growing in godliness and holiness is part of how the scriptures describe the believers life.

This is why sanctification can sometimes be understood in terms of ‘definitive’ sanctification (the explicit biblical view expressed) and ‘progressive’ sanctification (the process of growing in godliness and holiness). Generally when people say ‘sanctification’ they mean progressive sanctification.

(Note: Calvin generally associated what I’ve called here ‘sanctification’ with ‘regeneration’ and lifelong ‘repentance’. So we need to pay attention to the meanings people are attaching to their words.)

Future judgment

This is the big kahuna which so influenced and drove Luther’s reading of Romans. The primary concepts associated with final judgment are righteousness, works and salvation. A positive judgment leads to salvation and eternal life. Condemnation with lead to wrath and eternal punishment. What does it mean to receive a positive judgment at the end times?

I’ve written a long article on the subject here.

The reformers understanding of the final judgment is generally heavily influenced by their doctrines of righteousness and justification. If the judgment is by works (so also salvation by works) then to their mind all are doomed because no one is righteous / sinlessly perfect. Which is why the concepts of grace and faith are prominent in their understanding of the judgment of believers and questions like, ‘Why should I let you into my heaven?’ and ‘What do I have to do to inherit eternal life?’ are driving their theology.

(Note: Following again from my comments on ‘righteousness’ and ‘justification’ I observe the following statements from Jesus. It is only the ‘righteous man’ who will be rewarded (Mt 10:41). At the end of the age ‘the angels will come and separate the wicked from the righteous’ (Mt 13:49) and ‘then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father’ (Mt 13:43). It is not the ‘resurrection of sinners’ but the ‘resurrection of the righteous’ (Lk 14:14). All these passages point to one thing: only ‘the righteous’ will enter into ‘eternal life’ (Mt 25:46). In my view the ‘righteousness’ here does not mean sinless perfection or perfect obedience. This is not how Jesus’ audience would have understood righteousness.)

Imputation

Imputation takes words or actions and ties them to a person or a cause. The word is commonly applied to the Greek verb λογίζομαι transliterated as ‘logizomai’. I wrote a post on this some time ago.

The reformed understanding of imputation is set in the context of their understanding of righteousness and final judgment as discussed above. There are two ways imputation can be applied to justification. Passive and Active obedience.

The first is that a believers sin is imputed to Christ and he dies the death we deserve as punishment for our sins. This effectively propitiates God’s wrath and expiates our sin. This understanding is virtually synonymous with forgiveness of sins. This is commonly associated with Christ’s passive obedience on the cross.

But the so called ‘classic’ reformed view is also that for a person to be regarded righteous in God’s sight (sinless perfect obedience) they need to have some sort of positive righteousness. Because sinners cannot be perfectly obedient, most reformers also speak of the imputation of the active obedience of Christ to be believer. Or should I say believers are ‘credited’ with Christ’s righteousness. This novel creation is the foundation of the Covenant of Works.

(Note: I’ve written a bit of stuff on justification in my New Perspective page.)

Union in Christ

Some people say the centre of Paul’s thought is ‘union in Christ’. This little expression is used to encompass the following in Paul’s writings: In Christ, In the Lord, In Him, Into Christ, Into Him, With Christ, With the Lord, With Him and Through Christ.

First and foremost people are said to be in union with Christ because they believe in him. Faith unites a person to Christ. Hence the work of the Spirit is to give the gift of faith which then unites a person to Christ. Calvin is well known for his focus on union in Christ. His first section of book three is titled.

“1. The Holy Spirit the bond which unites us with Christ. This the result of faith produced by the secret operation of the Holy Spirit. This obvious from Scripture.” (Instit. 3.1)

The expression denotes the interrelationship between Christ and his people. Those in Christ are Christians. Union in Christ has connotations of corporate identity.

Another aspect of union in Christ I’ve seen people focus on in relation to this relationship is that whatever happens to Christ happens to his people. This is a function of his representative role for all his people as their king. Christ died, therefore all died in him. Christ was buried, therefore all were buried in baptism with him. Christ was raised to new life, all are raised to spiritual life. The terms ‘incorporation’ (e.g. Bird) and ‘participation’ (e.g Sanders) are commonly employed to describe what happens to believers because they are united to Christ.

The same concept is also applied by some to suggest that everything that is Christ’s is also his peoples. In particular his performance of God’s law and his ethical character. The forces driving the theology behind imputation also come into play with union in Christ. This aspect of union in Christ also has in mind righteousness, justification and final judgment. Those in Christ are ‘clothed’ in his perfect obedience, righteousness and are therefore themselves righteous in God’s sight. Union in Christ achieves the same end as imputation but in a different way.

Backing and Forthing

In my opinion, ever since Luther came up with his interpretation of ‘justification by faith alone apart from works of law’ the reformed faith has had a deep suspicion of any teaching or doctrine that advocated obedience or works. Consequently it regularly downplays any role attributed to obedience or good works in any part of salvation and criticises anyone who says they are important. Let me call this a first order doctrine for the reformers.

An early reaction by the Roman Catholic church to this stance was the charge of antinomianism. Correspondingly, the reformers further defined their argument by speaking about active faith and building in nuanced understandings of salvation that required repentance and obedience. Again, let me define these as second order doctrines.

I’m guessing the reformed generally focus on first order doctrines to promote their distinctive message and stand out from the ‘works-oriented’ religions and in particular the Roman Catholic church. They only use second order doctrines when required.

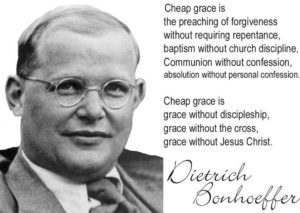

Some time after the reformation Dietrich Bonhoeffer coined the famous expression ‘cheap grace’ in reaction to a general neglect of upholding the nuanced necessity of repentance and obedience for salvation.

Some time after the reformation Dietrich Bonhoeffer coined the famous expression ‘cheap grace’ in reaction to a general neglect of upholding the nuanced necessity of repentance and obedience for salvation.

Again we are seeing the same in this book.

My main point is this backing and forthing happens all the time in reformed circles (e.g. the Gospel Coalition’s sanctification debate here and here).

I think this is because the reformers have misunderstood what Paul meant by ‘justification by faith alone apart from works of law’ and are therefore caught in error. Something they would never admit.

Essay Summaries

Ch 1 Preaching the Faith That Is Never Alone (By John H. Armstrong)

As the title suggests this essay is on preaching. More specifically the intention and method of preaching the gospel. Armstrong is responding to Jones. They seem to be on friendly terms.

Armstrong gives a great summary of the reformed focus on expository preaching.

John R. de Witt argues, quite convincingly I believe, that what characterises preaching in the New Testament is:

- It is an exposition of the Word of God. We are dealing with the scriptures when we preach rightly. …

- The application of the Word of God. Exposition and application must be linked together. … Truth must be driven home by the preacher. It has more than a cognitive function, it also has a moral dimension.

- But these two are not enough. Preaching is also proclamation. The word ‘preach’ means exactly that. It is to proclaim and what is proclaimed, or better put, who is proclaimed, is the important part here. The message the preacher brings is not his own, it is the message of his master, the message from God. …

- The final quality de Witt cites in biblical and Reformed preaching is freedom. This he argues, is the apostles Peter’s point when he writes: ‘If you speak, you should do so as one who speaks the very Word of God’ (1 Pet 1.12). There is some restriction places on contemporary preaches who handle the Word of God. Calvin understood this correctly when he wrote: ‘[The difference between the apostles and their successors is that] the former were sure and genuine scribes of the Holy Spirit, and their writings are therefore considered oracles of God; but the sole office of others is to teach what is provided and sealed in the Holy Scriptures.’ (Institutes 4.8.9)

This prophetic function of the ministry of the Word must be maintained at all costs.

His chief claim which was criticised by CJPM is that gospel ministry which proclaims the righteousness of God for salvation does more than simply administer forensic justification. He argues it involves transformative aspects as well.

The ‘righteousness of God’ is understood as more than a righteous status. This means this righteousness, or justice, is both forensic and effective. It is this second conclusion, that the righteousness of God that justifies us, is effective, that is denied by those who write in Covenant, Justification and Pastoral Ministry (CJPM).

They deny this because they are deeply concerned to protect the gospel from the intrusion of human works. …

This mono-perspectival reading of Paul ends up missing the arguments the apostle actually makes. It seems to me they do this because they are locked into a framework that reads Paul through Luther’s lens (only forensic) and not Paul’s.

I disagree with him slightly here. Following NT Wright and Rodriguez, the righteousness of God Paul refers to (Rom 1.16-17) in the gospel is God’s faithfulness to his covenant promises through Jesus Christ. But I do agree the proclamation of this gospel (which is what Paul alludes to when he says ‘righteousness of God’) makes believers righteous in his sight (forensic) and transforms them (effective).

Armstrong believes there is a close interrelationship between justification and sanctification. This also was what caused the authors of CJPM to criticise his work (and even Douglas Moos!) because he did not claim the gospel was about distinguishing justification from sanctification.

Ch 2 Faith and Faithfulness (By Norman Shepherd)

In CJPM Godfrey says,

‘If no one ever comes to you after you preach the gospel and asks, ‘So should we sin so that grace may abound?’ You have probably never preached the gospel” (CJPM, 280)

And,

‘Would anyone ever read the federal-vision writers or Norman Shepherd or the new perspective on Paul or Thomas Aquinas or the Council of Trent and come with the question to them: Should we sin that grace may abound?’ (ibid)

Shepherd’s response to Godfrey’s ridicule is to say the difference between them is that he preaches a living and active faith. A faith that is always accompanied by works (Jas 2.14-26). (54)

He also says Jesus commanded the disciples to teach all he commanded (Mt 28.19-20). God’s people do what Jesus commanded, including the command to love one another (Jn 15.9-10; 1 Jn 3.23; cf. Gal 5.6). (54)

He describes several instances in scripture where gospel proclamations call people to repent. To turn from sin and towards God and do good deeds in keeping with repentance. The pursuit of eternal life requires doing good (Gal 6.8). (55)

Shepherd reads as if he is quite angry. He constantly refers to himself in the third person. Godfrey must have provoked him.

In line with this (Jn 15.9-10) Jesus taught his disciples to evangelise the world by teaching the nations to obey everything he commanded. And this is exactly what they did, not only orally but also in writing. We have proof in our New Testament. The whole of each epistle is gospel, not only the promises made to faith but also the commands that are received by faith, faith that is living, active, penitent and obedient. The good news is not that God forgives impenitent sinners, but that he forgives penitent sinners.

Because Shepherd teaches that saving and justifying faith is living, active, penitent and obedient faith, Godfrey is quite certain that no one listening to him preach the gospel would ever raise the question ‘Should we sin that grace may abound?’

It is different, however when Godfrey preaches the gospel. Presumably, when he is finished, crowds gather around the pulpit breathlessly inquiring, ‘Then why shouldn’t we sin so that grace will abound?’

Why is there such a different response to the gospel Godfrey preaches?

The answer is that Godfrey preaches justification by faith alone, and he really means a faith that is alone. It is not a living and active faith that justifies as Shepherd says, but a faith that is all alone. He writes, ‘Paul really could not be clearer. Paul indeed taught that faith stands alone in receiving justification from the work of Christ ([Rom.] 3:24-26)’ (CJPM, 282) …

When Godfrey preaches the gospel he does not tell sinners to repent of their sins, nor does he tell them to obey all that Jesus has commanded. In other words, he does not preach the gospel the way Jesus commands us to preach the gospel in the Great Commission. If we do what the Great Commission tells us to do then we mix what David Van Drunen calls a “cocktail” of faith and works (CJPM, 49). And it is a toxic cocktail because if we tell sinners to repent and obey our Lord, Godfrey and Van Drunen think we are teaching them to justify themselves by their own good works. They find this to be contrary to Paul’s teaching that we are saved by faith alone and not by works of the law. (FNA, 57)

Soon after this Shepherd compares Godfrey’s statements against the Westminster Confession and Calvin’s Institutes. He argues Godfrey is in disagreement with the both regarding justifying faith and repentance (58-62).

He demonstrates fluency with other well known reformers Turretin and Bavinck.

Shepherd goes on to say that Godfrey’s basic problem is that for him the coexistence of faith and works implies, even requires coefficiency. The combination creates a toxic cocktail of faith plus works for justification (62).

While discussing key Pauline texts, he implies a couple or more times Godfrey is more Lutheran his theology than reformed. He differs from Godfrey on the definition of works of law. Godfrey he says believers Paul means any work and in particular good works. Shepherd argues Paul is talking about the Mosaic covenant (67). Following this Shepherd finally explains the rationale behind the question, ‘Should we sin so that grace may abound?’ in Rom 6.1.

Shepherd sums up stating we should not set faith and faithfulness over against each other as antithetical. I agree.

Ch 3 Reformed Covenant Theology and Its Discontents (By Mark Horne)

Horne begins by outlining the purpose of his response to Michael Horton who is a bit of a reformed pin up boy at the moment.

My claim is simply this: Zacharias Ursinus (an early source, principal author of the Heidelberg Catechism) is not a heretic. Francis Turretin (a much later source) does not deny the Gospel. The Westminster Standards (a confessional standard in my own Reformed denomination in which I am a minister) do not articulate a false soteriology. Reformed people are free to quibble about whether they would want to state things in the same way, but Ursinus, Turretin, and the Westminster divines as they have come to us in their ratified documents cannot be cast off as departures from the Reformed Faith. …

My response will fill holes in Dr. Horton’s portrayal, and the material I quote will make clear to those familiar with the Federal Vision that it is not at odds with how mainstream Reformed Covenant Theology deals with the conditionality of Scripture. (74)

It seems Horton has claimed Horne and a few other contributors of FNA from the Federal Vision have departed from ‘Mainstream Reformed Covenant Theology’.

Horne begins by quoting a series of questions and answers from the Westminster Shorter Catechism, the Westminster Long Catechism, and John Owens Shorter Catechism which espouse what the Federal Vision authors have written (74-77)

The questions discuss various conditions of salvation. These conditions are faith, repentance and new obedience.

He then says these Catechisms are representative of Mainstream Reformed Covenant Theology (77). Thus correcting Horton’s misunderstanding.

He then quotes several times from Zacharias Ursinus. A second generation reformer. Ursinus gives a nuanced position describing how good works are necessary for salvation (77-82).

He then quotes several times from Francis Turretin. His quotes show, again nuanced positions regarding salvation and works, merit and the covenant of grace. Turretin seems to advocate the covenant of works / grace framework.

Horne then discusses a disagreement between Ursinus and Turretin regarding imputation.

One notable disagreement between these two men who have been set out, was their respective views of the imputation of the active obedience of Christ (i.e. that Christ’s obedient works throughout his life are imputed to us, while the imputation of the passive obedience of Christ refers to Christ’s suffering and death on the cross) (90)

To describe the disagreement Horne quotes from the Commentary on the Heidelberg Catechism. Gosh! He knows his reformed theology. Disagreeing with Horton, he argues for Ursinus, the righteousness sinners receive in Christ by faith is the righteousness of Christ’s “passive obedience.”

Horne has some criticism of Horton’s own portrayal of his opponents and his ignorance of the reformers he has quoted. He believes Horton has a fictional standard of ‘orthodoxy’ (102). He reviews several of Rich Lusk statements regarding imputation and union with Christ and evaluates Horton’s response of them.

His discussion of Horton’s theology contrasts his depiction of the relationship between imputation and union with Christ against the Westminster Confession. Horton claims, ‘imputed righteousness the legal ground of union” (CJPM,204). In response Horne says the ordo salutis of the Westminster Standards is;

- Calling, Regeneration and Faith, leading to

- Union with Christ, which has the benefits of

- Justification (by faith), Adoption and Sanctification

I read Calvin’s Institute’s a while ago. This is Calvin. Horne then backs himself up from the Westminster Catechisms and concludes his essay.

Ch 4 From Birmingham, With Love: A “Federal Vision” Postcard (By Rich Lusk)

I found this essay to be quite a valuable expression of Reformed Systematic Theology. It is the longest in the whole collection (54 pages). In it Lusk is in strong agreement with Michael Bird regarding imputation and Union in Christ in this essay (see Bird, Saving Righteousness of God).

His essay has a series of what he calls ‘postcards’. Small chapter headings which unravel a progressive argument about imputation. I decided to have some fun and create some postcards with memorable quotes.

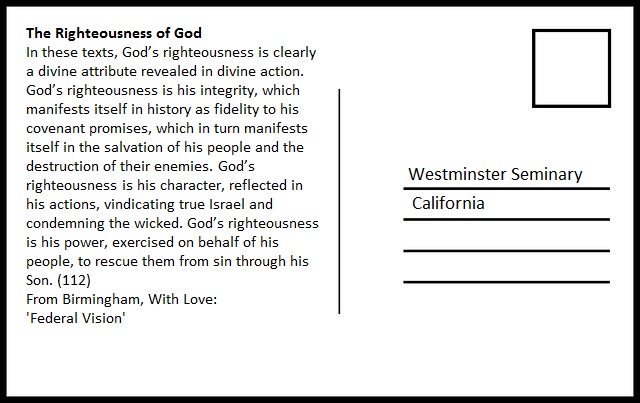

The Righteousness of God

I’m in strong agreement with this statement. I find Lusk’s discussion is quite eirenic. He seems to incorporate several aspects of God’s righteousness debated about today. He refers to God’s ethical character (e.g. Piper) and God’s covenant faithfulness (e.g. Wright), his saving activity (e.g. Bird) and his just judgment on sin (e.g. Seifrid).

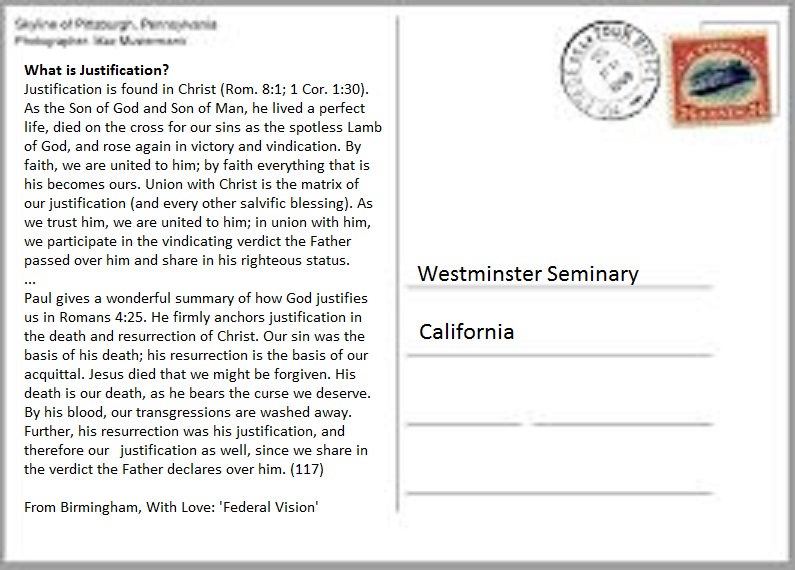

What is Justification?

I find this hard to fault as an expression of the reformed understanding of justification. I see a focus on Jesus’ sinless life, his death and resurrection, justification as a forensic term, and possibly penal substitutionary atonement. He links them all together under the rubric of union in Christ. I’ve seen the same in Garlington, Bird and Calvin.

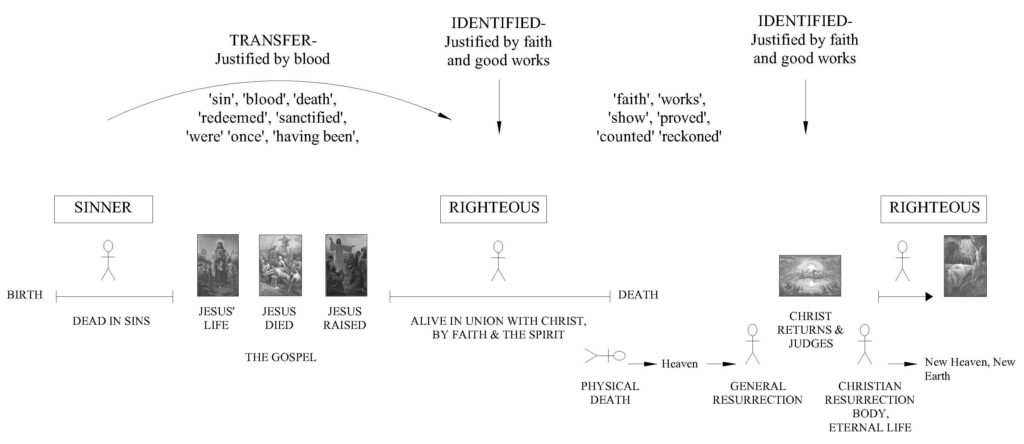

While this definition is pulling in a lot of helpful stuff from Paul’s theology I struggle with this. We perhaps need to remind ourselves that Paul did not define his terms. He used words that were assumed by the society he was writing in. That’s how language works. I realise sometimes he put more emphasis on one aspect or another. Or even he built upon the core meanings of these words. But justification in my mind is primarily about how something wrong is made right and how something right is identified as such. Hence my diagram.

I realise Lusk’s definition is an extension of the first, however I like to keep it simple.

Justifying Faith: Living or Dead?

Full agreement. This postcard is just like reading Norman Shepherd’s essay again. Faith is never alone. There is nothing wrong with commanding and promising obedience when the gospel is proclaimed. Only an active faith saves. It saves not because of its obedience. It saves because it lays hold of Christ.

The Meaning of Imputation

Taking into account my comments above. Full agreement. Lusk gives a breakdown of Romans 4. The key chapter for considering imputation. He helpfully recognises Abraham is an existing believer in God, quoting Gen 12, Heb 11. A point many ignore. He only briefly considered Rom 4.4 and did not note this verse is core to double imputations argument.

The Imputation of Christ’s Active Obedience and Inclusive Substitution

Wright and Garlington are advocates of the New Perspective who have rejected the imputation of Christ’s active obedience. Hence the topic of this humorous video modification.

Carson, Piper and Horton are well known proponents of the supposed ‘classic reformed view’ of double imputation. Piper has a section in his book, Future of Justification addressing Wright on this topic.

What critics of the New Perspective constantly neglect to mention is that it is an intra-refromed debate. Gathercole, Gundry, Seifrid and Hoekema are contemporary scholars who do not hold to the imputation of Christ’s active obedience.

Lusk gives brief discussion to 2 Cor 5.19-21; Phil 3.9 focussing mainly on Rom 4. I found this illustration quite amusing.

I find it encouraging there is a ‘rising generation of scholars’ questioning the doctrine.

This story highlights the obvious legal fiction involved in double imputation.

My own journey into these issues began when I was a newbie Bible study teacher years ago. I was teaching a group of kids a lesson on justification [as you do in Sunday School?!?] and used a familiar illustration that went something like this:

Imagine that you have to take a test on quantum physics. You are clueless, completely unable to answer any of the questions correctly. You write in answers, but all of them are wrong. You are bound to fail. But then Someone comes and offers to take the test for you. He erases all your wrong answers and writes in perfectly correct answers. He then hands in the test with your name on it.

After giving the illustration, I asked the kids, “What would you call that?” I was expecting an answer that pointed to the graciousness of the arrangement. I was expecting them to note that erasing the wrong answers corresponded to Christ’s blood; writing in the right answers corresponded to Christ’s life of perfect obedience. Instead, a rather precocious junior high boy blurted out “Cheating!” (145)

Justification, Legalism, and Corporate Identities

Here Lusk describes how I understand Don Garlington’s and Michael Birds understanding of the implications of justification and union in Christ. Note the focus on soteriology and ecclesiology, individual and corporate. His statement again is quite eirenic in my opinion.

Conclusion

In this last postcard Lusk captures some of the tone of the debate used on both sides. It’s quite hard not to think some authors of CJPM are quite belligerent and narrow minded.

I honestly don’t know much about the Federal Vision. What I do know is mainly from this book and what they say here seems fine. ?

Ch 5 Adam the Catholic? Faith and Life in the Adamic Covenant (By Peter Leithart)

Just as a heads up, this essay is not particularly flattering to Catholics. The title only made sense to me after reading the bulk of the essay at which point Leithart explained his meaning.

Leithart begins his essay with a description about a theory of ‘natural’ vs. ‘supernatural’. The topic deals with the innate abilities of man before and after receiving God’s grace.

The textual background to this essay is Paul’s depiction of the headship of Adam and Christ as expressed in Romans 5 and it’s interrelationship with the Garden of Eden account in Genesis. The Garden of Eden account is seen through a covenantal lense.

First he explains he will be addressing another who’s position is close to Horton’s. Some guy named Byran Estelle.

In one of his first sections Leithart outlines a series of points in which he and Estelle are in agreement.

- Adam was in covenant with God.

- God commanded Adam not to eat from the tree of knowledge.

- Adam was a representative of the whole human race, so that his sin introduced sin and death into the world and brought all his seed under the reign of sin and death.

- Adam was supposed to obey on pain of death.

Biblical Theology is structured by the parallels of the First and Last Adams.- Adam’s probation was temporary.

- Adam was created with a built-in eschatological trajectory.

The prohibition against Adam eating the tree of knowledge was a test of his allegiance.- God is king and judge.

- The New Perspective writers, and E. P. Sanders in particular, raise “a whole host of issues with which New Testament Scholars and scholars in related fields must now grapple and perhaps even nuance or adjust previously held opinions” (p. 126, fn. 146). (174)

From this point onwards the majority of the essay is devoted to picking apart Estelle’s account of the Adamic Covenant. Leithart says Estelle spends most of his time arguing for the uncontroversial and scant little on points under considerable contention.

Near the end of the essay Leithart sums up Estelle’s position.

Estelle is suggesting that Adam was already accepted and beloved as a son, but needed to obey in order to reach some higher condition, then he is not so far from those he opposes. If, on the other hand, he is suggesting that Adam needed to obey in order to earn, by a “works principle,” the favor of God, then he is indeed differing with his opponents. He is saying that Adam was created a Catholic, but became a Protestant after he fell. Protestantism is reduced to a postlapsarian form of Christianity.26 Worse, he is suggesting that God Himself began creation as a Catholic merit-based project, but turned things in a Protestant direction because of the fall.27 (186-87)

He then pushes this onto Horton.

For Horton, in short, Adam had to earn his right to the tree of life, and had to earn that by obeying from his own resources, resources given to him by virtue of his creation. For Horton as for Estelle, the tree of life represents eschatological life, entry into Sabbath. For both, Adam was not created with free access to life. For both, faith and works function differently before and after the fall. For both, humanity begins its life as a Catholic and falls into Protestantism. (188)

And I thought the allegorical method of interpretation was strained.

Sigh. I have no wish to disrespect Leithart. So my apologies, I struggled with this essay the most. I struggled to agree with the blatant imposition of the reformed understanding of grace, faith and works imposed by both sides on the Garden of Eden account in Genesis. I considered this eisegesis on the part of both sides.

I do tend to think Adam was a historical figure. That being said, the framework I view the Garden of Eden account through is Israel’s relationship with God in the promised land. Being kicked out of the garden is the mythical depiction of Israel’s exile.

If I compared Romans 5.12-21 with the Garden of Eden account, other than the connections between Adam/Christ, Transgression/Obedience, I fail to see why I should impose this covenantal framework on the text.

Ch 6 The Gospel of Law and the Law of Gospel (By P. Andrew Sandlin)

Sandlin’s essay is a response to Clark’s understanding of Gospel and Law, which encompasses the covenant of works explanatory system. After critiquing Clark’s merit theology gospel, Sandlin puts forward his own understanding of the relationship between law and gospel.

- Scott Clark, following Martin Luther and a significant segment of the Reformed tradition, has argued that Gospel and Law are mutually exclusive divine messages from God to man:

- Law is the message of “Do this [actively] and live”;

- Gospel is the message of “Rest in Jesus [passively] and His work alone.”

- Law is the demand for human performance before God.

- Gospel is the assurance of Jesus’ performance on our behalf that invites our passive reliance (“resting and receiving”).

Essential to this theological construct is the Covenant of Works, which holds that eternal life is the reward for man’s entire, unblemished obedience to God’s commands. Eternal life is merited by man’s righteous works established by God. In the covenant administration before the Fall, Adam was capable of performing these works and therefore of winning eternal life for himself and the entire human race, but his sin disqualified both him and us from this path to gaining that life. Jesus Christ, as the New Adam, has fulfilled the standard demanded by the Covenant of Works in his active, Law-keeping life (“active obedience”) as well as His Law-keeping death (“passive obedience”). In justification, this legal obedience is imputed (legally credited) to the believing sinner. Man is saved largely on the ground of Jesus’ Law-keeping, which merits eternal life for man. At its foundation, eternal life is a reward for works-righteousness. Since man can no longer perform those works impeccably, Jesus performs them on his behalf. Foundationally, therefore, God deals with man on the basis of Law — “Do this and live; fail to do to it and die.” Gospel is the means of fulfilling this Law after the Fall: Jesus keeps the Law and merits God’s favor as a substitute for man. This is the antithetical Gospel-Law paradigm. (242-43)

Sandlin begins his rebuttal of Clarks Law-Gospel by showing how faith is both penitent and obedient. He does a good job of this. Because he is discussing the makeup of faith with regard to justification, repentance and obedience Calvin might be in order here.

But we are furnished with a still clearer argument. Since faith embraces Christ as he is offered by the Father, and he is offered not only for justification, for forgiveness of sins and peace, but also for sanctification, as the fountain of living waters, it is certain that no man will ever know him aright without at the same time receiving the sanctification of the Spirit; or, to express the matter more plainly, faith consists in the knowledge of Christ; Christ cannot be known without the sanctification of his Spirit: therefore faith cannot possibly be disjoined from pious affection. (3.2.8)

and

we must hold that the only hope which believers have of the heavenly inheritance is, that being in grafted into the body of Christ, they are justified freely. For, in regard to justification, faith is merely passives bringing nothing of our own to procure the favor of God, but receiving from Christ everything that we want. (3.13.5)

We can see in the first quote Calvin’s classic position regarding justification and progressive sanctification (which includes repentance and obedience). They are distinct, yet inseparable.

In the second quote Calvin says ‘in regard to justification faith is merely passives’ suggesting that in regard to other things such as repentance and obedience faith can be quite ‘actives’.

Sandlin seems to capture same thought when he corrects Clark.

Sinners are not saved by trusting in themselves, their own good works or merit or achievement. They are saved by faith in Jesus Christ alone. In this sense, faith is rightly identified as resting and receiving [passives]. However, Clark equates this resting and receiving with passivity (CJPM, 362-363). This passivity apparently prohibits the inclusion of repentance and submission to Jesus as constituent elements of faith: [according to Clark] these acts may (even must) follow saving faith, but they are not of the essence of faith. (217)

I think what we see here is a nuanced distinction between Calvinistic and Lutheran understandings of justifying faith.

Then he outlines his understanding of the gospel. His understanding is similar to Gilbert’s. Only he starts with the Acts passages (focussing on the salvation bits as McKnight said of Gilbert) conveniently building repentance and lordship into his gospel. Eventually summing it up thus:

The unified Gospel-Law paradigm of the Bible depicts salvation as the work of God entirely. God reconciles the world in the Person of Jesus, Who died for man’s sins on the Cross and rose again for his justification. If man casts himself by faith on Jesus Christ alone, in a penitent faith that turns from his sins and submits to Jesus as Lord, trusting only in Him and not in himself or his deeds, he will be saved. This is a salvation wholly by God’s grace, not of works, merit, or human achievement. It is the work of God, not of man. This lawful gospel is the only authentic message of salvation to a dying world. (246-47)

Like Clark, his gospel is thoroughly soterian. So I disagree. The gospel is the story of Jesus (e.g. Mk 1.1). See the links in the glossary pointing to my understanding of the gospel. Otherwise, many of the reformed persuasion would be in strong agreement.

Ch 7 The Imputation of Active Obedience (By Norman Shepherd)

In this essay Shepherd is responding to Clark’s assertions that the imputation of Christ’s active obedience is biblical and the only historical position of the reformers.

Shepherd begins with the history of the doctrine starting with Calvin.

Shepherd begins with the history of the doctrine starting with Calvin.

To give some context, in his Institute’s, Calvin begins his discussion of Justification (Calvin, Instit. 3.11.1) by comparing what he thinks it means to be ‘justified by works’ and what it means to be ‘justified by faith’.

Shepherd quotes an important passage I’ve seen Piper use against Wright (Future of Justification). Shepherd’s quote (p251) however I think he skips over some things that set the context so I’ve included them here.

In the same manner, a man will be said to be justified by works, if in his life there can be found a purity and holiness which merits an attestation of righteousness at the throne of God, or if by the perfection of his works he can answer and satisfy the divine justice.

On the contrary, a man will be justified by faith when, excluded from the righteousness of works, he by faith lays hold of the righteousness of Christ, and clothed in it appears in the sight of God not as a sinner, but as righteous. (Calvin, Instit. 3.11.2)

(Note: Shepherd quotes from Battles, please forgive me any Calvin snobs out there for quoting from Beveridge).

I observe the typical reformed glossing with ‘works’ to be any work, not just from the law of Moses. Also the divine comparison issue involving perfection (remember my glossary). I also note Calvin says ‘clothed in’ which is potentially union in Christ language. Taking this further he says ‘clothed in it’ or ‘clothed in [the righteousness of Christ]’. Given the context Calvin has defined ‘righteousness’ as ‘perfection of works’ this puts weight on the interpretation that Calvin thinks justification by faith includes being clothed in Christ’s perfection of works.

Not taking into account the immediate context this is what Shepherd quotes.

Thus we simply interpret justification, as the acceptance with which God receives us into his favour as if we were righteous; and we say that this justification consists in the forgiveness of sins and the imputation of the righteousness of Christ (Calvin, Instit. 3.11.2)

Of this quote he says;

The key to understanding Calvin is his point that justification consists in the remission of sins. Because our sins are forgiven, we are accepted as righteous men and received into God’s favor. This forgiveness is obtained by the imputation of Christ’s righteousness, and (as will be discussed below) for Calvin the righteousness of Christ that obtains forgiveness of sin is the passive obedience of Christ, specifically his death on the cross for us and in our place. As Calvin goes on to explain his teaching in section 3, there is no mention of or reference to the imputation of active obedience because justification is the remission of sins, and this forgiveness is not grounded in the imputation of active obedience. (251)

From this point onwards Shepherd quotes and refers to a series of sections in Calvin, the Heidelberg confession and even the Roman Catholic depiction of the reformers positions in the Council of Trent to argue his point.

I’ve sourced similar quotations from Calvin myself to argue the same so I agree with Shepherd here. But there still remains the above and I think one or two other sections of Institute’s that are in conflict. Such as;

The Apostle declares this more plainly when he says, that “he made him to be sin for us, who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him,” (2 Cor. 5:21.) For the Son of God, though spotlessly pure, took upon him the disgrace and ignominy of our iniquities, and in return clothed us with his purity. (Calvin, Instit. 2.16.6)

I deny Calvin was under the inspiration of the Spirit when he wrote Institute’s (I think what many reformed secretly affirm) so therefore remain open to his thought developing over time or he simply contradicted himself.

The situation changes, however, in the latter part of the sixteenth century and on into the seventeenth century as we move from the “mature Reformation” into the period of “scholastic confessionalism.” (Arthur C. Cochrane, Reformed Confessions of the 16th Century) The doctrine of the imputation of Christ’s active obedience is embraced in tandem with the development of the doctrine of a covenant of works. The two go hand in hand and necessitate each other. Nevertheless, the rejection of the imputation of active obedience was represented by delegates to both the Synod of Dordt and the Westminster Assembly of Divines, and interestingly enough, by the chairmen of both these assemblies. (31) Therefore the Canons of Dordt and the Westminster Standards have to be understood historically as allowing for this position, though clearly it had become a minority view and has remained a minority view among the Reformed since that time. (262)

I can back this up myself from John Owen.

(2.) There hath been a controversy more directly stated among some learned divines of the Reformed churches (for the Lutherans are unanimous on the one side), about the righteousness of Christ that is said to be imputed unto us.

For some would have this to be only his suffering of death, and the satisfaction which he made for sin thereby, and

others include therein the obedience of his life also. (See http://www.puritanlibrary.com/ Volume 5 of 21 (on Justification). page 63)

Shepherd then deals with the biblical arguments Clark advances for IAO. He notes their brevity and reliance on theological rather than exegetical arguments. The main passages he considers are Rom 5.19; Gal 4.4; Phil 2.8 and Heb 5.8.

Like Lusk mentioned previously, Shepherd still advocates the necessity for Christ’s perfect obedience. Not so that it can be imputed to believers, but in order to establish Christ as an unblemished sacrifice. (267)

Towards the end he critiques Clark’s theological arguments. The covenant of works is discussed and argued against.

I’ll finish on this. Shepherd seems to have a sense of humor. This made me laugh.

As noted above about the covenant of works and as Clark describes it, divine justice, and therefore justification, requires both the remission of sins and the imputation of active obedience. The cross can keep us out of hell, but it cannot get us into heaven.

In this Clark is in full agreement with Trent that justification is not merely or solely the remission of sins as Calvin and the early Reformation taught, but also requires obedience. For Trent, that obedience was an inwrought (infused) and out wrought (good works) obedience. Together these constitute sanctification, and sanctification defines what justification is.

For Clark and those who share his commitment to the covenant of works, the required obedience is an imputed, active obedience. In other words, it is an imputed sanctification. Thus, just as Trent confuses justification and sanctification by defining justification as sanctification, so also Clark confuses justification and sanctification by defining justification as sanctification. (272)

Ch 8 The New Perspective, Mediation and Justification (By Don Garlington)

Don Garlington was the original reason why I purchased the book in the first case. I wanted to read more of what he says about the New Perspective on Paul and he is one of the lesser known advocates. Like Michael Bird in several respects, seeing the social implications, as well as the salvific, from being united in Christ.

In this essay he is responding to Baugh. The essay is structured giving a brief introduction to Sanders and Dunn and their positions regarding the Reformation. Then he addresses a series of points and criticisms Baugh has levelled at Wright and the New Perspective. Not all Baugh says is rejected. Garlington on several occasions agrees with him and commends him for his contributions.

Here are some of the points I found interesting.

When mud is getting thrown around, it’s easy to lose sight of what people have really said. Here is one of Dunn’s points regarding Luther.

Lutherans understood “justification by works” in terms of a Roman Catholic system where believers earned salvation through the merit of good works. This was based partly on the comparison suggested in Romans 4:4-5 and partly on the Reformation rejection of the Roman Catholic system that supposedly allowed one to accumulate merits and buy indulgences. But Dunn’s qualification,that the Reformation’s repudiation of merits and indulgences is an important emphasis, is often neglected. God is the one who justifies the ungodly (Romans 4:5), and, Dunn says, understandably this insight has become a powerful, integrating focus in Lutheran theology. A careful reading of Dunn clearly reveals that his agenda is stated in hermeneutical terms. The protest against merits and indulgences was necessary, justified, and of lasting importance. But the hermeneutical mistake was to read this antithesis back into the New Testament period and to assume that Paul was protesting in Pharisaic Judaism precisely what Luther protested in the pre-Reformation church. It is true that Dunn programmatically pursues this “new perspective” throughout his commentary, but Paul’s theology is hardly given a complete overhaul. In many places, Dunn’s comments on the text of Romans are as traditional as any other commentator. (284)

Garlington weighs in on some of what Wright’s says.

Wright, by contrast, maintains that justification does not tell us how one can be saved; it is, rather, a way of saying how one can know that one belongs to the covenant community, or, in other words, how are the people of God to be defined? (Wright, What Saint Paul Really Said)

Paul does indeed address the question, “Who is a member of the people of God?” Likewise, it is true that “justification … is the doctrine which insists that all who share faith in Christ belong at the same table, no matter what their racial differences, as together they wait for the final new creation.” (ibid)

This much said, it is to be acknowledged that Wright has distinguished too sharply between the identity of the people of God and salvation.

In my view, it is closer to the mark to say that (among other things) Romans and Galatians do address the issue of entrance into the body of the saved, meaning that to belong to the new covenant is to belong to the saved community. Therefore, justification does indeed tell us how “to be saved” in that it depicts a method of redeeming sinners—by faith in Christ—and placing them in covenant standing with the God of Israel. If justification is by faith, then a mode of salvation is prescribed. (286)

Garlington has some helpful points here. I do think ‘faith in Christ’ both describes how a person can enter the community of the saved (becoming righteous) and how one can tell they are part of that community (identification of the righteous).

However I get a little nervous when ‘faith in Christ’ is associated with the former. Because all too often people who focus on the former ignore the latter.

I think this is Paul’s main focus in writing to Gentile believers. In Romans and Galatians Paul’s audiences are already part of the saved community and thus the greater focus is not on how they can be saved (they already are), the focus is on how they can tell they are saved (Jews telling them they need to observe the works of law).

Wright maintains that “the discussions of justification in much of the history of the church, certainly since Augustine, got off on the wrong foot— at least in terms of understanding Paul—and they have stayed there ever since.” (287)

I’ve demonstrated this in my series on Justification in the Early Church.

I would simply affirm Dunn’s contention that Romans 5:1 marks the beginning of the salvation process: justification is not a once-for-all act; it is the initial acceptance by God into restored fellowship (as indicated by the aorist tense “having been justified” (dikaiōthentes) of Romans 5:1) …

Since the present concern is with Romans 5, I would invoke the same verses as Dunn, Romans 5:9-10: …

I have treated the passage elsewhere. Suffice it to say here that Christ’s resurrection gives the believer hope, a hope that looks forward to the future eschatological consummation of the new creation. …

Paul polarizes past and future in our salvation experience. Because of what Christ has already done, we have the assurance that although the consummation of redemption has not been completed, the believer can take comfort that God’s purposes cannot fail. In this light,the aorist “having been justified” of Romans 5:1 is to be given its due within the spectrum of the “three tenses” of salvation history: “I have been saved, I am being saved, and I will be saved.” (303-4)

Agreement.

Ch 9 Future Justification: Some Theological and Exegetical Proposals (By Rich Lusk)

Lusk’s second essay is intended to be a starting point for further discussion on what he calls ‘final justification’. He focusses in particular on Rom 2.1-16 and Jas 2.14-26 quoting from numerous other passages in support.

The doctrine of the final judgment / justification has remained fairly underdeveloped in Protestant thought and pastoral practice. In the Reformed tradition, we have not known exactly what to say about future judgment texts, and so we have not said much at all (as perusal of the standard systematic theologies shows). The result is that we have mitigated, and even muted, an important part of God’s Word. This essay seeks to address that imbalance. (309-10)

Lusk begins by quoting a number of sections from the Westminster Confession. His quotations serve to give him room for speaking about similar things when he looks at scripture without leaving himself open to being ridiculed as a Roman Catholic by his CJPM opponents.

The Westminster Standards do not speak explicitly of a “future justification,” but they do provide the conceptual framework within which I have developed the doctrine offered here. The Westminster Standards insist on obedience as a necessary condition of eschatological salvation in a variety of ways. Faith must bear “fruit,” which has as its end “eternal life” (WCF 16.2). Forgiveness is only given to the repentant (WCF 15.3).Initial justification is inseparable from sanctification, perseverance, and good works (WCF 10-18). God requires repentance if we are to escape his wrath and curse (WSC 85). Holy obedience is not only evidence of salvation, but the way of salvation (WLC 32). Our good works are “accepted” by God in Christ, so that he, “looking upon them in His Son, is pleased to accept and reward” them (WCF16.6). (310)

When working through Romans 2.1-16 Lusk works through a series of points. After evaluating Rom 2.6-11 and 2.16 he asks the following question.

If initial justification is already settled by faith alone, why is there a final justification according to works? Because there is more to salvation than bare acceptance. That acceptance is glorious, but it is only the beginning, not the end. Ultimately salvation is about glorification. (330)

I would say the final judgment is according to works because God’s judgment has to be impartial. God has to judge believers in the same way as non-believers in order to be just. Why are non-believers punished? Why are they left unsaved to face God’s wrath? Because of their evil works, their sin and rejection of God. What does this say of how God will judge his own people? Our understanding of the basis of believers judgment has to be the same as the basis non-believers are judged by if we are to maintain the impartiality of God’s judgment and therefore his justice.

Afterwards he has an interpretation of Numbers 19 and it’s water purification rituals which I found a little strange. He argues is is a text which clearly speaks about double justification and resurrection.

When he gets to James he argues James is speaking about future justification.

This is a justification that is posterior to works. In other words, this passage has nothing (directly) to do with initial justification, which clearly precedes works. James deals here with eschatological salvation (2:12-14). In the illustrations given (Abraham and Rahab), it is clear that they are already believers well before the justification in view is declared. (This is clearer in the case of Abraham, obviously.) These illustrations foreshadow, model, and typify eschatological justification. James is discussing our final acquittal before the judgment seat of God; he is providing historical paradigms for understanding future justification. (348)

Personally I think of James primarily addressing present justification, but I have no problem recognising Jas 2 also applies to future as well. Lusk finishes on this note.

Initial justification is by faith alone. But it is by a faith that will prove itself in works. Final justification is by faith and works together. Or, to put it differently, it is by a faith that has proven itself in obedience and borne the fruit of the Spirit. This is the teaching found across the board in the NT. (354)

Ch 10 Covenantal Nomism and the Exile (By Don Garlington)

Garlingtons second essay is a response to Duguid who was in turn responding to Sanders pattern of religion (‘Covenantal Nomism’). Duguid attempts to undermine Sanders pattern by comparing the covenants within the Old Testament. He says the earlier Mosaic covenant was conditional on Israel’s obedience to which we all know Israel failed and was sent into exile. But the new covenant promised would be unconditional and fulfilled in the coming Messiah.

Garlingtons second essay is a response to Duguid who was in turn responding to Sanders pattern of religion (‘Covenantal Nomism’). Duguid attempts to undermine Sanders pattern by comparing the covenants within the Old Testament. He says the earlier Mosaic covenant was conditional on Israel’s obedience to which we all know Israel failed and was sent into exile. But the new covenant promised would be unconditional and fulfilled in the coming Messiah.

In Garlingtons own words;

In his essay, Professor Duguid has endeavored to challenge the ideology lying behind the coinage of E. P. Sanders’ phrase “covenantal nomism.”

The gist of the argument is that this moniker cannot be an accurate portrayal of covenant relationships, because it is the faithfulness of the Lord, not human beings, that ensures the continuance of the covenant.

According to Duguid, there are both conditional and unconditional covenants in Scripture. Among the most prominent of the conditional covenants is the Mosaic. But even the blessings of that covenant are to be received unconditionally, through a sovereign act of God’s mercy and grace, at the time of Israel’s return from exile, when the new covenant is established.

In the final analysis, it is Christ the covenant servant who has fulfilled the conditions of the covenant.

As I read him, however,these findings a replaced in service of a rather startling conclusion: for all practical purposes, perseverance is unnecessary and unrequired.. I doubt that Duguid would want to express it in these terms, but such is the consistent outcome of his thesis. (388)

Garlington agrees with many things Duguid says, but he disagrees with the core argument he is trying to prove. Garlington evaluates Duguid’s argument by looking at both Old and New Testaments texts. He shows quite well that the new covenant is conditional on the perseverance, repentance and obedience of its members.

In my response, I have concurred that God’s grace is always primary, indispensable and the source of every blessing that flows from the covenant(s). Each biblical covenant is initiated sovereignly and graciously in fulfillment of the Lord’s eternal design to have a people for himself, and we are kept by the power of God for a salvation to be revealed in the last day (1 Peter 1:5).

And yes, the Lord Jesus Christ is the faithful and obedient servant (Philippians 2:5-11) who has fulfilled the conditions of the covenant.

None of these data are in dispute, and it is inconceivable that any believer would call them into question. Without him, we can do nothing.

Where I differ is in my assertion that every covenant is conditional, in the sense that the human partner is obliged to maintain faith with the God of the covenant. Therefore, if Christ has fulfilled the conditions of the covenant, it is to the end that we do the same. (388)

Recommendation

I recommend this book to anyone who would like to learn about more nuanced reformed positions on how perseverance, repentance and obedience fit into the process of salvation (justification, sanctification, etc).

The book is quite dense and is a heavy read. It’s like going to a restaurant and ordering a 500g steak for dinner. Eating it is quite enjoyable. However eventually you will get full and might find it hard to finish and you’ll be digesting it for days afterward.

The book is quite dense and is a heavy read. It’s like going to a restaurant and ordering a 500g steak for dinner. Eating it is quite enjoyable. However eventually you will get full and might find it hard to finish and you’ll be digesting it for days afterward.

It contains extensive quotations from early and contemporary reformers. Without a doubt the contributors are competent scholars in the reformed faith and display a broad knowledge in their field.

The book demonstrates that within the reformed camp, there are many important aspects to faith, works and salvation that have not yet reached a consensus.

I found the book is a bit repetitive at times. This is to be expected because they are all responding in some way to a common argument about justification and works presented by CJPM.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2016. All Rights Reserved.