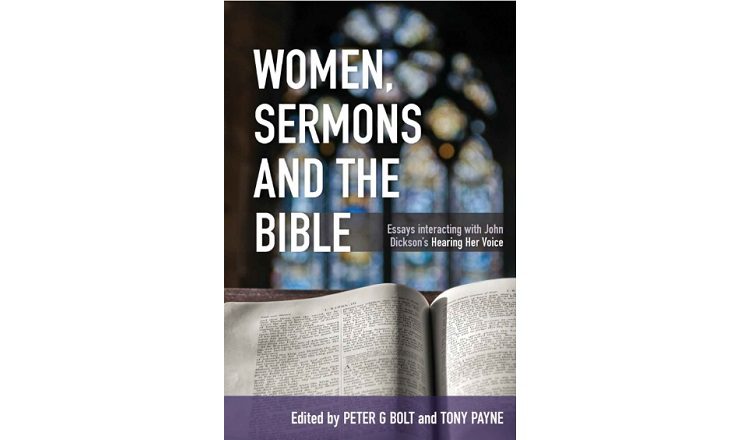

This book was specifically written as an attempted rebuttal to John Dicksons book Hearing Her Voice. Generally I found the book quite disappointing. In addition it’s almost twice the size of Dicksons book.

This book was specifically written as an attempted rebuttal to John Dicksons book Hearing Her Voice. Generally I found the book quite disappointing. In addition it’s almost twice the size of Dicksons book.

- Link: Amazon

- Length: 298

- Difficulty: Medium-Easy

- Topic: Topical, Women, Preaching

- Audience: Mainstream Christians

- Published: 2014

Overall, reading the varied and numerous arguments surrounding the debate involves a considerable amount of going back and forth between each of the books to read and make sure each is correctly understood. It’s like being a ball in a tennis match!

This book review is one of three in which I did some reading on the arguments surrounding women giving sermons. The other reviews are:

- Dickson, J., Hearing Her Voice A Case for Women Giving Sermons (Link), and

- Bird, Bourgeois Babes Bossy Wives and Bobby Haircuts (Link).

This post is one of my book reviews.

Contents

- Introduction: Ordinary and unusual (Tony Payne and Peter G Bolt, editors)

- Part I: Setting the scene

- 1. Doing theology in a digital culture (Peter Tong)

- 2. One woman’s voice: some personal reflections on the realities of complementarian ministry (Dani Treweek)

- Part II: Biblical and historical arguments

- 3. Unchanged ‘teaching’: The meaning of didaskō in 1 Timothy 2: 12 (Claire Smith)

- 4. Can the Old Testament be ‘taught’? (Claire Smith)

- 5. Is the modern sermon an ‘exhortation’? (Claire Smith)

- 6. Reading God’s history as our good news (Peter G Bolt)

- Part III: Reflections on method and theology

- 7. God’s word then and now (Tony Payne)

- 8. Preachers and leaders (Lionel Windsor)

- 9. The theological ground of evangelical complementarianism (Mark D Thompson)

- Appendix: Observations from the second edition (Claire Smith)

Main points

Publishing History

This is a revised edition of Hearing Her Voice. There is an unfortunate history regarding this revision and the response it was given. In Dickson’s own words.

Readers of Women, Sermons and the Bible have a right to ask how well they have been served by this book. Matthias Media requested and received a copy of the revised version of HHV at the beginning of August 2013, a month before it was available to the public, nine months before WSB was published.

The original request from Matthias Media in July 2013 stated, reasonably enough, “I know you’re keen for robust discussion and for serious and thoughtful responses to your argument, so in the spirit of all that I’m wondering whether you’d be willing to send us an advance PDF of your second edition? Just so that those who are writing are interacting with the most recent version and with your latest thoughts, rather than with outdated material.” That made sense, so I agreed, and I sent the revision as soon as it was finished (5 August 2013). I don’t think my question is unfair: How is it that those who were writing their responses to the first edition between January–July 2013 could not thoroughly revise their material in light of the second edition between August 2013 and April 2014? We are all busy people, but this debate deserves better.

I cannot see how the authors of WSB can claim to have defeated my argument—as they do often enough throughout the book—when I do not recognise my argument in their work? Independently of me, evangelical bishop-scholar Dr Tim Harris has noted the same thing: “I am disturbed that John Dickson really doesn’t seem to have been portrayed in reasonable terms” and “I suspect Dickson would be most unsatisfied with how he has been represented (I would be!).” (Dicksons Reply)

If I tabulate the relevant dates of communication.

| John Dickson | Matthias Media |

| Jan 2013 – Hearing Her Voice (HHV); published | |

| Jan – Jul 2013 – Helpful feedback to his original | |

| Jul 2013 – Requested HHV Revised Edition | |

| Aug 2013 – HHV Revised Edition; written | Aug 2013 – Received HHV Revised Edition |

| May 2014 – Woman, Sermons and the Bible; published (interacts with original 2013 version) | |

| Aug 2014 – Hearing Her Voice, Revised Edition; published |

Basically Matthias Media botched it up. Their review mostly interacts with mistaken views of Dickson’s arguments.

1. Doing theology in a digital culture (Peter Tong)

Dicksons book, Hearing Her Voice A Case for Women Giving Sermons, and Birds book, Bourgeois Babes Bossy Wives and Bobby Haircuts were published electronically together with one other book. The release of the books caused a bit of an internet stir. Tong considers the positives and negatives of releasing ideas like this online with respect to the old fashioned way of publishing books.

2. One woman’s voice: some personal reflections on the realities of complementarian ministry (Dani Treweek)

Treweek seems to be quite offended that Dickson has not acknowledged the contributions women already give in complementarian churches. Women are not as oppressed and held back from ministry as one might think. I found this a fair argument. Many women are happy with the limited roles they can be involved in. Preaching in church to men is not everything.

3. Unchanged ‘teaching’: The meaning of didaskō in 1 Timothy 2: 12 (Claire Smith)

These next three chapters constitute the bulk of interaction with Dicksons argument. Her arguments need to be considered in light of Dicksons response here.

| Smith’s Argument | Dickson’s Response |

|

Dickson argues that Smith largely ignored the distinction he made between the general and specific senses of teach.

Dicksons interpretation is widely recognised with scholars who have written commentaries on the Pastoral Epistles. He contacted some of the scholars he used and they supported his argument. |

|

Dickson defended his arguments. Sometimes contacting the living supporters directly who then said Smith had misunderstood or misused them. |

|

Dickson regrets the language he used when saying ‘teach’ means ‘laying down the apostolic deposit’. He refined his true intention saying when Paul uses ‘teach’ in the Pastoral epistles he refers to ‘the laying down of apostolic deposit’. He is not changing the meaning. |

|

Dickson argues that Smith largely ignored the distinction he made between the general and specific senses of teach.

Dicksons interpretation is widely recognised with scholars who have written commentaries on the Pastoral Epistles. He contacted some of the scholars he used and they supported his argument. |

Throughout Hearing Her Voice Dickson tried to show that Paul’s references to “teacher” (didaskalos), “teach” (didaskō), and “teaching” (didaskalia / didachē) have a special focus on transmitting the apostles’ memories and rulings about Jesus and the new covenant in a period when hardly any of it was written down. He argues the noun “teaching” refers to the content of the apostolic traditions, the verb “teach” refers to the activity of instructing people in these traditions, and the noun “teacher” refers to the personnel set apart in the church to perform this authoritative duty.

Smith claims;

“This definition is at the heart of the book’s argument. In fact the language of ‘laying down and preserving’ occurs some 60 times. While it lacks clarity, and is put to various uses throughout the book, what is clear is that this meaning of ‘laying down and preserving’ is different from the accepted meanings of didaskō that we saw above in the history of the word and its use in the first century … In fact, if generations past had understood didaskō to mean what Dickson claims it means, the consistent decision of translators in various languages to translate this Greek word as ‘teach’ is at best mystifying, since ‘teach’ and ‘laying down and preserving’ are in no way synonymous.

What Dickson is proposing is a new meaning of the word, one that is otherwise unattested in writings outside the New Testament or in translations of the Bible. His proposal marks a significant shift in the meaning of the word, so that it no longer refers to an educational activity that causes people to learn, but to an activity that preserves and lays down content. In short, his new definition focuses on the effect of the activity on the content, not on the interaction between teacher and student with resulting effect on the one who is learning” (WSB chapter 3 §3)”

Smith is mistaken to assume the special usage Dickson refers to means a new definition. All Dickson outlines in his book is that Paul is using the word ‘teaching’ in a particular way. The meaning of the word is the same but its usage or reference is more specific.

Lets consider what a few articles say about ‘teach’ in the Pastoral Epistles;

As to the meaning of “teach,” given the use of the word and its cognates in the Pastoral Letters, it probably refers to the authoritative communication of “the faith,” that is, the apostolic doctrine, with the witness to Jesus and his teachings at its core. (Footnote 11: See especially didasko in 1 Tim. 4:11; 6:2; 2 Tim. 2:2; didache in 2 Tim. 4:2, and didaskalia in 1 Tim. 1:10; 4:6, 13, 16; 5:17; 6:1, 3; 2 Tim. 3:10, 16; 4:3; Titus 1:9; 2:1, 7, 10) (99, NIVAC 1Ti-Tt)

The teacher was above all a transmitter of the tradition about Christ (Cf. Gal 1.12), which tradition was received by the churches and to which they must remain true. … In sum, ‘teaching’ according to Paul involves the careful transmission of the tradition concerning Jesus Christ and His significance and the authoritative proclamation of God’s will to believers in the light of that tradition. (65-6, Moo, ‘1 Timothy 2:11-15: Meaning and Significance,’ Trinity Journal (1981): 169-170)

To “teach” (didaskein) is to provide instruction in a formal or informal setting (L&N 33.224; cf. Luke 11:1). The Greek term for “teach doctrine” is katēcheō (cf. English “catechism”; Luke 1:4; Acts 18:25; 21:21, 24; 1 Cor 14:19; Gal 6:6). “Doctrine” as a system of thought assumes that authority lies in the act of teaching (or in the person who teaches).

Yet, in the Pastorals, authority resides in the deposit of truth—literally, “the mystery of the faith” (3:9), “the message of faith” (4:6), “the faith” (4:1; 5:8; 6:10, 12, 21), and “the trust” (6:20) that Jesus passed on to his disciples and that they in turn passed on to their disciples (2 Tim 2:2). So “doctrine” with this definition was not a first-century development. That is why Paul instructed Timothy to publicly rebuke (5:20) anyone who departed from, literally, “the sound instruction of our Lord Jesus Christ” (6:3). The teacher was subject to evaluation and discipline just like any other leader or minister. (58, Cornerstone Biblical Commentary: 1-2 Timothy, Titus & Hebrews)

I suggest further reading may be necessary. However from these I see a common grain of thought that the content of the teaching Paul refers to is the communication of the gospel narrative and the apostles teachings.

Smith rarely interacts with Dickson’s starting argument that Paul differentiates between ‘teaching’ and ‘exhortation’.

All the same, ‘teaching’ and ‘exhorting’ are not synonyms. There is an important difference between them that informs our understanding of both 4:13 and 6:2. Paul is broadening the educational landscape.

Teaching (cf. didaskō; didaskalia), as we have seen, is primarily concerned to produce learning in a pupil.

Exhorting (cf. parakaleō; paraklēsis), on the other hand, might produce learning, but the focus is on the relational dynamic of a speaker coming alongside the hearer to use personal influence to persuade the hearer and move them along.

Both may produce learning and transformation, but they do so in different ways. (Loc 1486)

The question Smith seems to be ignoring is: Are women allowed to give sermons which are better defined as ‘exhortations’?

4. Can the Old Testament be ‘taught’? (Claire Smith)

In this essay Smith attempts to argue there are strong theological and exegetical reasons for including the Old Testament as the content matter of teaching. She argues that both the Old Testament and the Apostles teaching are the word of God and therefore Paul’s prohibition of women to teach therefore applies to both. Also that there are many quotations from the Old Testament in the New. Smith interacts with 2 Tim 3.16; Rom 15.4; and the New Testament in general.

In this essay, Smith continues to ignore the distinctions Dickson has made between the general sense of teaching, the specific usage of teach in the Pastoral epistles and exhortation. The essay thus largely fails to interact with Dicksons argument.

5. Is the modern sermon an ‘exhortation’? (Claire Smith)

In part Smith attempts to argue that Dickson’s distinction between ‘teaching’ and ‘exhortation’ is untrue. She ignores Romans 12.4-8; 1 Tim 4.13 and 2 Tim 4.2 which form part of the biblical basis for Dicksons argument.

Smith argues from Acts 13.15 that when Paul was in the synogogue he was asked for a word of ‘exhortation’, but his message also included elements of what Dickson defines as ‘teaching’. The telling of the gospel story. Smith does not consider to think Paul gave them more than what they asked for. Exhortation of the OT and teaching of the apostolic deposit.

Smith also attempts to argue the epistle to the Hebrews cannot be a word of exhortation as Dickson claims because it is ‘more full of the life, death, resurrection and current ministry of Christ, and its implications’ (Loc 2459) than ‘Old Testament scripture’. Therefore she argues its content is the subject matter of ‘teaching’ not ‘exhortation’. I’m not sure she has really quantified the amount of OT material in Hebrews correctly in proportion to the gospel. I tend to agree with Dickson here.

Smith highlights that Jesus teaches in the Synagogue (Lk 4.15, 31). She ignores Dicksons argument for the distinction between the general and specific sense of teaching. I see no reason to think Jesus was teaching in the general sense here.

6. Reading God’s history as our good news (Peter G Bolt)

Part of Dicksons argument involves a gap in time between the gospel history and when they and the epistles were committed to writing. In the time between these two, Dickson argues the ‘teachers’ had the role of being repositories of the gospel accounts and the epistles. They were responsible for their reliable transmission in the church during the absence of written scripture. He argues Paul adopted the Pharisaic model of what a teacher did. The Pharisees in the first century had a large body of oral teachings and traditions not committed to papyrus.

Bolt highlights this general model of argument has a history itself being endorsed by the Brethren Symposium, John Stott, Gilbert Bilezikan, JI Packer, Graham Cole and now John Dickson. He questions the validity of this hypothesis and whether it is true or not. He rightly highlights the oral teachings of the apostolic deposit were not committed to writing at the same time. Most churches would have varying amounts of written scripture. Bolt quotes the early church father Tertullian to undermine Dickson’s argument women were allowed to teach.

Personally I’m not convinced by Dickson that the office of teacher was restricted to being the custodian of oral teachings and scriptures. I believe the office also included being the custodian of written scriptures as well.

7. God’s word then and now (Tony Payne)

Payne recognises a trend of interpretation where the biblical text is interpreted in its historical context. The method could be used to narrow the meaning of certain texts and highlight that it meant different things than it did at the time of writing than it does now approximately two thousand years later.

He argues against this with several NT quotations of the OT saying they applied scripture written a long time ago and applied them to their contexts. He argues from this that nothing of significance separates us from the hearers/readers of the New Testament.

I wasn’t convinced by his argument. I believe sometimes there are some tangible differences between our times and not all texts can be readily applied to our own contexts.

8. Preachers and leaders (Lionel Windsor)

Windsor argues that preaching should be understood as the means by which a congregational leader ministers to the congregation under his care. In this way he ensures that the truth handed down in the Scriptures is learned and obeyed by that congregation.

Dickson seems to make a distinction between teaching and holding a position of authority in church. Windsor argues those two roles cannot be easily separated.

9. The theological ground of evangelical complementarianism (Mark D Thompson)

Thompson gives his opinion of the nature of the Trinity. In particular the relationship between the Father and the Son, their equality, the Son’s subordination and how this impinges upon the relationship between men and women.

Recommendation

In my opinion this book largely fails to interact with Dicksons argument. Many of the things they say are true. But they end up shooting down straw men. They don’t seem to have paid much attention to what Dickson has argued.

Readers of this book need to read Dicksons Revised version of Hearing Her Voice and his response to the book here. Then they need to understand the logical sequence of ideas Dickson applies in his argument. If both arguments are compared they will see WSB largely missed the mark.

That being said there are some weaknesses to Dicksons argument that still need to be fleshed out. As I mentioned before I believe the office of ‘teacher’ also included being the custodian of written scriptures as well as the oral.

This book helpfully broadens the scope and implications of the debate.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2017. All Rights Reserved.