- Link: Amazon

- Length: 99

- Difficulty: Medium to Easy, Popular

- Topic: Theology, Paul

- Audience: Mainstream Christians

Because I am sympathetic to the New Perspective interpretation on Paul’s use of justification I take it upon myself to be aware of the criticisms and books written against it. Stephen Westerholm, a well-known opponent of the New Perspective, has written this book to reach the popular reading level. So I thought I would give a review of his work.

In the preface Westerholm explains the aim of his book is both to update and to make more widely accessible earlier works he has done, especially Perspectives Old and New on Paul: The “Lutheran” Paul and His Critics. I’ve read both of these books.

The purpose of this review is to show:

- I read and understand books like these,

- Show they have errors and omissions of their own,

- Defend my own views reasonably from scripture.

It is a long review compared to the size of the book because refuting arguments like this takes time.

This is one of my book reviews.

Contents

The Peril of Modernizing Paul (Against Stendahl)

Westerholm begins by taking aim at Stendahl and challenging his theories about justification by faith and the introspective conscience of the west. I’ve reviewed Stendahl’s book here (Link).

Both Stendahl’s posing of the issue and his response—not “How can a sinner find a gracious God?” but “On what terms can Gentiles gain entrance to the people of God?”—have become axiomatic for many. (3)

Stendahl questions whether Luther read into Paul his social context. Westerholm in return questions whether Stendahl read his own context into Paul.

The Burden of Paul’s Mission: Thessalonica and Corinth

What moved Gentiles to enlist in a community of believers in the first place? Westerholm looks at the letter to the Thessalonians and notes Paul’s references to salvation from wrath associated with their conversion. He assumes the content of Paul’s gospel must have made them introspective and fearful of God’s wrath. That’s why he argues they believed the gospel.

Westerholm child’s Stendahl assuming he thinks that Paul’s gospel message invites them into the Abrahamic community on easy terms.

Westerholm moves on to consider the Corinthians correspondence. Still arguing for his understanding of the gospel he brings in the concepts of justification and says:

One way, then, of putting the dilemma addressed by Paul’s gospel is to say that the world is peopled by the “unrighteous” who, as such, cannot hope to survive divine judgment. The gospel responds to that dilemma by offering the unrighteous a means by which they may nonetheless be “declared righteous,” or “justified” (6:11).

Such language, to repeat, is not prominent in Corinthians; but it is there, and it has to do, not with whether Gentiles need to be circumcised and keep Jewish food laws, nor with how Gentiles can be made equally acceptable before God as Jews.

Paul invokes the language of righteousness and justification when he indicates how sinners can find the righteousness they need if they are to stand in God’s presence. (8-9)

Westerholm is basically advocating a reformed soterian understanding of the gospel which is based on the Lutheran reading of Romans 1-4.

The Galatian Dilemma

Westerholm says Paul’s initial message to the Galatians will have differed little from his message to the Thessalonians and the Corinthians. He seems to assume that when Paul had first come to Galatians, they were not already interested in Judaism and were adopting Jewish customs.

It’s in Galatians that Paul first writes about justification. Westerholm compares the NPP reading with the OPP reading on justified by faith apart from works of law.

[Stendahl] The formula has of late often been taken as an opening statement of his opposition: “A person (i.e., Gentile) is not justified (i.e., declared to be a member of God’s people) by works of the law (i.e., being circumcised, keeping food laws and the like) …” “To be justified” is thus construed as meaning “declared to be a member of God’s people,” “declared to be within the covenant,” perhaps even “declared to be a member of God’s family.” (13)

Vs.

[Westerholm] On the basis of what we have seen in the Thessalonian and Corinthian epistles, we would expect Paul’s justification formula to mean something like this: “A person (i.e., Jew or Gentile, but necessarily a sinner in either case) will not be found righteous (and thus delivered from the divine condemnation that awaits sinners) by works of the law (i.e., by complying with the law’s demands—since that is not what sinners do), but through faith in Jesus Christ.” (14)

Westerholm then gives his argument for interpreting Galatians. He argues Peter and Paul are sinners, unable to meet the demands of the law. He argues that those who rely on the works of the law are under a curse because no one can be righteous by the law and the law curses every transgressor.

At Rome and Philippi

Westerholm skips through a reading of Romans 1-5 mentioning the standard reformed key points of reference. He also mentions Rom 10.1-5 and finally Phil 3.9 texts on righteousness. He finishes with his basic argument about the question and answer of justification;

How can sinners find a gracious God? The question is hardly peculiar to the modern West; it was provoked by Paul’s message wherever he went. But Paul was commissioned, not to illuminate a crisis, but to present to a world under judgment a divine offer of salvation. In substance though not in terminology in Thessalonians, in terminology though not prominently in Corinthians, thematically in Galatians and regularly thereafter, Paul’s answer was that sinners for whom Christ died are declared righteous by God when they place their faith in Jesus Christ. (23)

My Response

Please read with my New Perspective page to get an understanding of how I distinguish between two different senses of justification.

Throughout his book, Westerholm adopts a miserable sinner understanding of Christianity. It’s hard to think he believes anyone is righteous. Rather it seems more like to him, everyone is a sinner and no one practices righteousness or keeps God’s commands. He only focusses on sin and refuses to look the general practice and behaviour of people, which is what the authors of scripture do. This is the pessimistic heart of Lutheranism that refuses to acknowledge scripture which says otherwise. It’s a core hermeneutic for determining the meaning of the scriptures and especially what Paul means by his justification expressions.

The upshot for this is that justification for him can never refer to the identification of the righteous. Because in his mind the righteous don’t exist. It means the righteous can never be identified by their practice of righteousness because according to him no one can keep the law, everyone keeps on sinning. It’s logical from this set of assumptions, justification could never make a person righteous or identify who is righteous. Rather is must be a declarative fiction which covers over the reality that everyone is a sinner and no one can be righteous in terms of their behaviour.

This I believe is Westerholm’s root problem and it works its way through his whole book.

Westerholm’s argument in this first chapter compares and contrasts what he understands as Paul’s gospel message with what he assumes is Stendahl’s take on Paul’s gospel.

Stendahl’s is well known for his essay on the western introspective conscience (Link) and his assertion Paul had a ‘robust conscience’ and was not deeply worried about his state before God. In trying to refute Stendahl’s argument, Westerholm ignores the scriptures Stendahl’s argument is based on (Phil 3.4-6; Acts 23.1; 1 Thes 2.10; 1 Cor 4.4). These passages reflect Paul’s understanding of himself before and after conversion. Paul believed he lived his life in good conscience, that he was righteous in conduct, and he was unaware of anything against himself.

Stendahl’s book is also known for his understanding of the historical context of Paul’s expression justification by faith. In contrasting himself to Stendahl, Westerholm presents an argument for what he thinks Paul’s gospel is. He believes Paul encouraged his listeners to introspection, liminality and to see themselves as sinners bound for God’s wrath.

For Westerholm, Paul’s message of ‘justification by faith’ is key to the message of the gospel given to sinners.

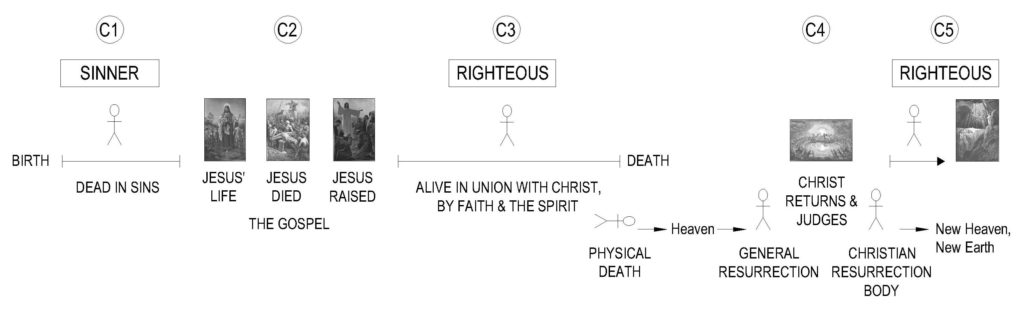

I think John Piper (Link) would certainly approve. But is this Paul’s gospel? Paul’s descriptions of the gospel in 1 Cor 15.3-5; Rom 1.1-5; 2 Tim 2.8; Acts 13.26-32 don’t seem to reflect a message expounding God’s wrath and putting his listeners into a state of introspective fear and liminality. Likewise I did my own study on the gospel sermons in Acts and found no explicit references to God’s wrath in any of the sermons.

I’ve written and reviewed a bit on the gospel over the years (page, series and review). It’s the story of Jesus, his birth, life, death and resurrection, presented as the fulfillment of the Old Testament promises and prophecies. This story declares Jesus the promised Christ, Lord of all and summons its listeners to the obedience of faith. I think, Westerholm has misrepresented what the content of Paul’s gospel is.

I agree from 1 Thessalonians that Paul must have called his audience to repent and turn from their idolatry, and he probably warned them of its consequences – God’s wrath. However I deny these are key elements of his gospel message. These elements are simply not common to all of his gospel presentations. Scripture, thousands of years of Christian belief, NT Wright, Scot McKnight and John Dickson seem to agree with me.

Westerholm wrongly argues that Stendahl thought Paul’s gospel message offered Gentile believers membership in the people of God on easy terms. Stendahl certainly refers to Paul’s calling and the gospel often enough. However looking closely I don’t think he defines what he thinks Paul’s gospel is.

Okay so if Paul proclaims the gospel to Gentile sinners and they believe what happens? Those sinners become righteous in God’s sight. In what sense? Westerholm uses 1 Cor 4.3-4 to argue that every instance of justification in Paul, including ‘justification by faith’, refers to a sinners acquittal. A mere declaration of righteousness. Paul in this verse assumes he will be acquitted if he is found faithful. Westerholm is wrong to assume this is a sinners acquittal. However, I think there’s more to justification.

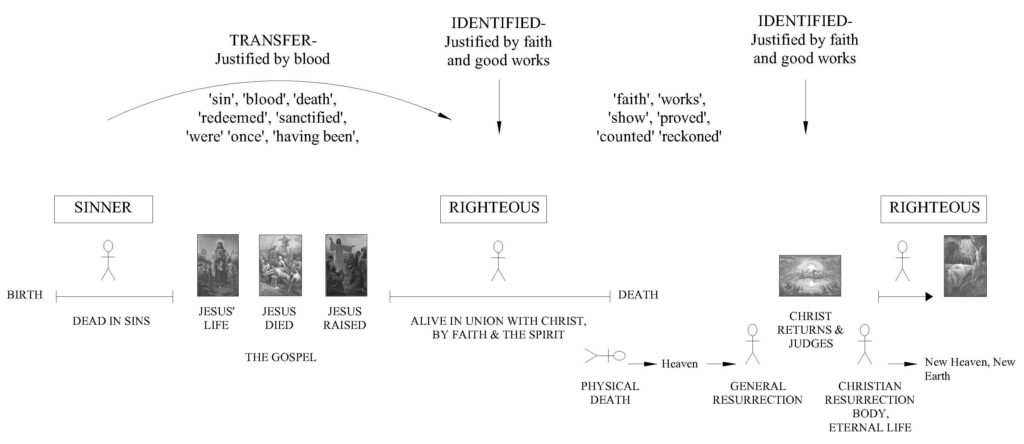

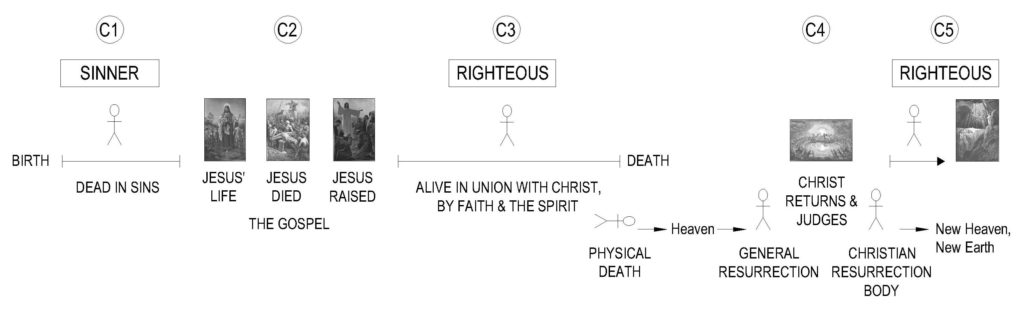

As I argue in my New Perspective page, sinners are made righteous (Rom 5.19). Not perfect. Righteous. Justification in one sense is a transfer term which denotes a change of heart and mind. The control centre of a person’s being. To be sure an event which saves from wrath, brings peace and reconciliation with God. But the righteous also practice righteousness, meet the apostles standard (Rom 6.17), walk with God and are blameless before Him. I think this is one way Paul uses justification language (Link).

But unlike Sanders and Westerholm, I don’t think Stendahl or Paul understand ‘justification by faith’ as a transfer term. They mean something else by it. NT Wright can explain how Paul’s gospel is then followed with Paul’s understanding of ‘justification by faith’ that Stendahl seems to be reflecting.

For Paul, ‘the gospel’ creates the church; [and afterward] ‘justification’ defines it.

The gospel announcement carries its own power to save people, and to dethrone the idols to which they had been bound [cf. 1 Thes 1.9?]. ‘The gospel’ itself is neither a system of thought, nor a set of techniques for making people Christians [Contra. Westerholm’s soterian gospel]; it is the personal announcement of the person of Jesus. That is why it creates the church, the people who believe that Jesus is Lord and that God raised him from the dead [cf. Rom 10.9-10].

‘Justification’ is then the doctrine which declares that whoever believes that gospel, and wherever and whenever they believe it, those people are truly members of his family, no matter where they came from, what colour their skin may be, whatever else might distinguish them from each other.

The gospel itself creates the church; justification continually reminds the church that it is the people created by the gospel and the gospel alone, and that it must live on that basis. (Loc 2670, NT Wright, What Saint Paul Really Said)

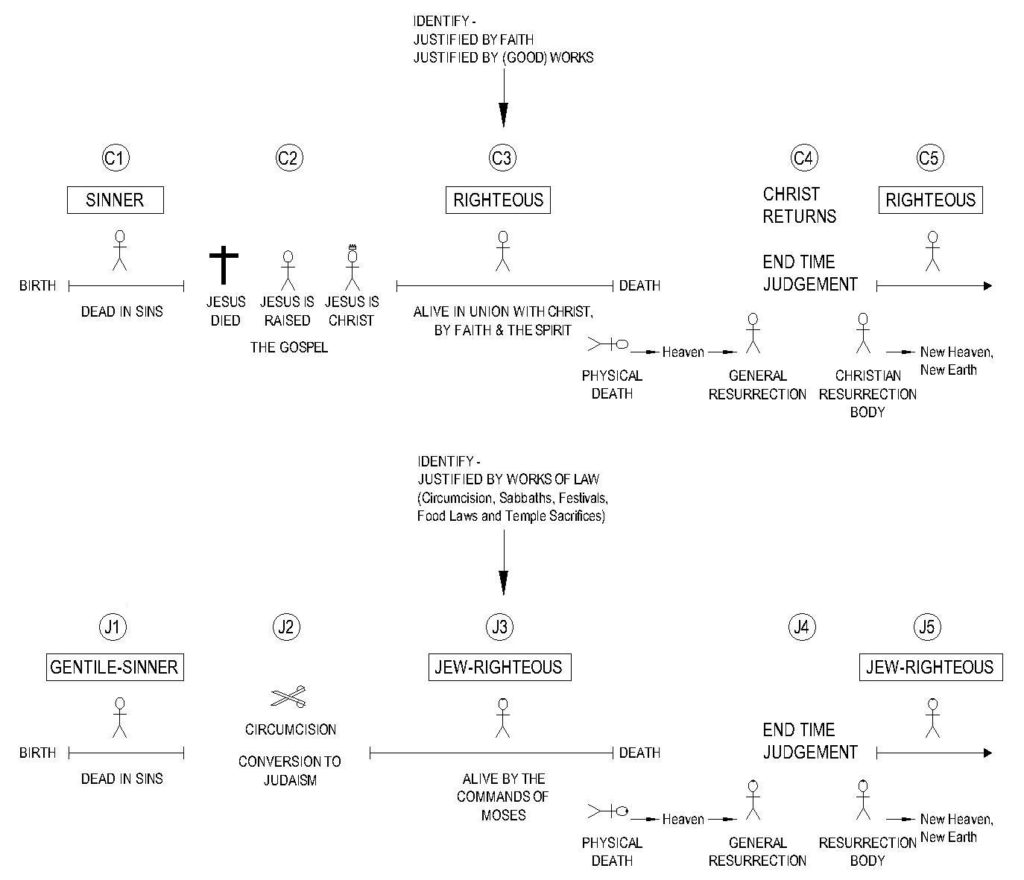

Stendahl’s argument assumes the Gentile believers (C3) were already righteous in God’s sight and at times under pressure from Jews, to accept circumcision and adhere to the law of Moses. That’s the historical context that Stendahl has in mind when he speaks of ‘justification by faith’. I.e. Believers who are already righteous, who are being told they are not because they don’t observe the law of Moses. Paul certainly has a Jew-Gentile context in mind when he speaks about justification by faith (Rom 3.28-30; Gal 2.14-16; 3.7-9, 23-29). I’ve written about this as well (Link).

For Stendahl, Paul’s message of ‘justification by faith’ is pastoral care given to existing Gentile believers who are righteous in God’s sight.

Even Barclay seems to agree on Paul’s use of justification to existing believers, contra Westerholm;

What Jewish believers have come to realize, through their “calling” in grace and their experience in Christ, is that the saving gift has already been given in Christ, without regard to worth, and that God considers “righteous” those whose new lives, evidenced in faith, have been generated from the Christ-event (2:19-20). To be “considered righteous by faith in Christ” is thus the result of the Christ-gift, not the condition for it. (377, Barclay, Paul and the Gift)

We should therefore resist the suggestion that the verb δικαιοῦσθαι takes on a new meaning in Paul, becoming a transfer term for “getting into the body of the saved” (Sanders, Paul and Palestinian Judaism, pp. 470-72, 544-46).

Westerholm rightly notes that the application of this term in Paul is extraordinary (Perspectives Old and New, pp. 273-84) but this is not because its meaning shifts, but because people are regarded as “righteous” on the basis of an extraordinary, incongruous gift. The verb does not change in meaning from “consider righteous” to “make righteous”; it applies to people who have been changed. (Footnote 73, Barclay, Paul and the Gift)

The new perspective reading assumes the Gentile believers Paul writes to in Rome and Galatia are already righteous in God’s sight and the chief problem they needed help with was to realise they do not need to be circumcised and adopt the law of Moses to be recognised as such. Paul wants them to know and feel assured they are righteous in God’s sight because they have faith and the righteous (both Jews and Gentiles) have always been identified by their faith (Rom 4.11-12, 23-25; Gal 3.7).

Paul’s message of justification by faith is not about telling believers they are sinners, under God’s wrath and therefore need to have faith in Jesus to be declared righteous in God’s sight. Paul’s message of justification by faith assures Gentile believers in the gospel they are already righteous and they don’t need to observe the law of Moses.

My readings of Romans 1-4 and Galatians have positions built-in them overcoming several of Westerholm’s other objections.

A Jewish Doctrine? (Against Sanders)

In this chapter Westerholm offers a critique of a scholar in Second Temple Judaism named EP Sanders. He is the author of a well known book in scholarly circles called Paul and Palestinian Judaism (PPJ) which I have reviewed here.

Judaism and Grace

First he summarises his understanding of Sanders argument.

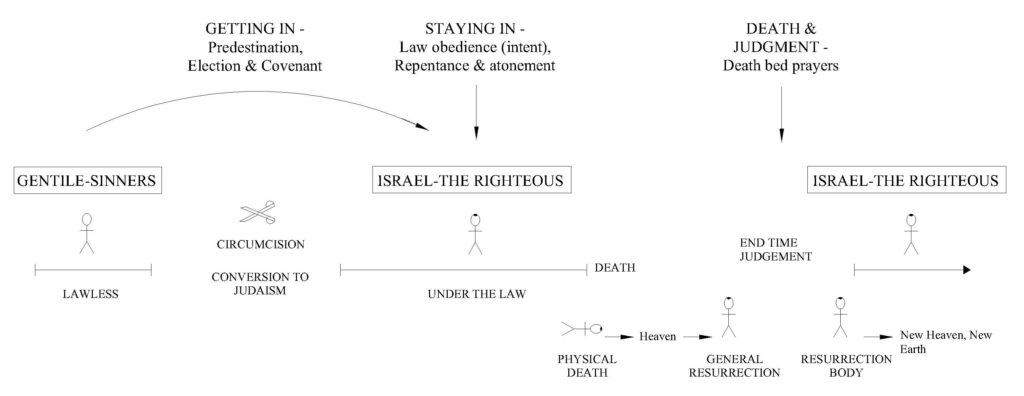

[Sanders argued] The rabbis could not really have thought that salvation was based on a strict measurement of one’s deeds, since they manifestly believed God to be merciful toward all those within the covenant who “basically intended to obey, even though their performance might have been a long way from perfect” (125); moreover, God “has appointed [for those within the covenant] means of atonement for every transgression, except the intention to reject God and his covenant” (157).

Sanders wrote: “On the point at which many have found the decisive contrast between Paul and Judaism—grace and works—Paul is in agreement with Palestinian Judaism.… Salvation is by grace but judgment is according to works; works are the condition of remaining ‘in,’ but they do not earn salvation” (543).

I think Westerholm understanding on these points is correct. However he has omitted the overall pattern of Covenantal Nomism.

Paul and Grace

Westerholm then moves to Paul. He skips over a several passages that refer to God’s grace and human sinfulness.

That Paul thought salvation is by grace alone, apart from human works, is clear enough (Rom 3:24; 4:4–8; 5:15, 17; 11:6).

On the human side, salvation is necessarily by grace since people are sinners, lacking both the inclination and the capacity to do the good God requires of them. Paul makes the point in a variety of ways: (Rom 3:9–11, 19; 5:6, 8, 10, 5:19; 6:20–21; 7:18; 8:7–8). (26f)

Now he thinks he is well placed to critique Second Temple Judaism with his reading of Paul.

Paul and Judaism

He gives three main arguments:

1. Sanders makes the point, explicitly and repeatedly, that a contrast between works or merit on the one hand and faith or grace on the other is not native to Judaism.

Westerholm strings together a series of quotes from PPJ showing the relationship between grace and works in Judaism. To this Westerholm responds;

For Paul (as we have seen), if something is “by grace,” it cannot be by “works,” since “otherwise grace would not be grace” (Rom 11:6). At this point, the head-scratching begins: How can his view of grace be the same as that of a Judaism that did not consider “grace and works” to be “opposed to each other in any way”? (31)

Basically he is saying the second temple Jews held together God’s grace and works. Paul by way of comparison considered God’s grace antithetical to human works.

2. The rabbis insisted on the merits of Israel, or of Israel’s forefathers, as a factor when God chose them for his covenant people.

Westerholm quotes from Sanders;

Sanders duly notes, for example, that, according to some rabbinic texts, God “chose Israel because of some merit found either in the patriarchs or in the exodus generation or on the condition of future obedience”. (32)

And then from Barclay;

John Barclay has pointed out that ancient notions of gift giving consistently took into account the worthiness of the recipient(s). Gifts were still gifts, to be sure; they were not earned. But neither were they to be given indiscriminately; giving a gift to those who would not appreciate it, or who would squander it, was wasted effort. Along these lines we may understand the rabbinic insistence on the merits of Israel, or of Israel’s forefathers, as a factor when God chose them for his covenant people: on nations that betrayed no interest in submitting to God’s will, the gift would have been wasted. Israel’s willingness to obey made them worthy recipients of what was nonetheless a divine gift, out of all proportion to their merits.

Against such (readily understandable) notions, Paul’s striking insistence on the utter unworthiness of the recipients of God’s grace stands out all the starker. (32)

Westerholm thus argues the Jews believed their election was based on some form of merit. He contrasts this with Paul who stresses the unworthiness of those whom God elects and saves.

3. For Paul, God’s gift of salvation necessarily excludes any part to be played by God-pleasing “works” since human beings are incapable of doing them. Human beings are all sinners, the “weak,” the “ungodly,” God’s “enemies.” They are slaves of sin. In their flesh lives no good thing.

Sanders noted the Rabbis did not have a doctrine of original sin or of the essential sinfulness of each man in the Christian sense. In response Westerholm speaks about Paul’s understanding of human sinfulness.

As long as one believes that (whatever is to be said of Gentiles) Jews will be “saved” provided they show a basic willingness to comply with the laws of the covenant (some Jews set the standard higher than that; but some did not), one will naturally believe them capable of showing at least the required modicum of obedience.

So Paul himself presumably believed prior to his life-changing trip to Damascus.

But once he was convinced that Jesus was, after all, God’s Messiah, then Christ’s crucifixion, far from discrediting messianic claims on his behalf, had to find a place in the divine plan for messianic redemption.

It follows that humanity’s predicament must be more desperate than Jews otherwise imagined. Human beings must not, after all, be capable of the modicum of obedience required by the covenant … Along such lines, we may well imagine Paul’s thinking developed. …

The fact remains that his depiction of humanity’s condition required a much more rigorous dependence on divine grace than did Judaism’s. (33-4)

Westerholm thus tries to establish a distinction between Judaism and Paul on whether human beings (believers and unbelievers) have some sort of ‘essential sinfulness’ which makes them completely reliant on God’s grace.

My Response

Westerholm’s intention is to give a picture of Paul which he can then contrast to his understanding of Second Temple Judaism. He wants to show Sanders depiction of Judaism is incorrect. He argues Judaism in the second temple period did not share the same understanding as Paul did of the plight of sinners prior to being saved, rather they had a merit theology which emphasised works-righteousness to which Paul was responded to with a message of God’s grace towards sinners.

I’ll respond to Westerholm’s three points in a different order.

2. The rabbis insisted on the merits of Israel, or of Israel’s forefathers, as a factor when God chose them for his covenant people.

Overall, Sanders covenantal nomism pattern of religion still stands. Westerholm hones in on the reason for their election (‘getting in’) in the first place.

Westerholm’s argument reflects the same assumptions and mistakes as Barclay’s does. I wrote a topical post on Barclay’s treatment of Sanders here (Link). Readers of Westerholm’s book who have not read Sanders Paul and Palestinian Judaism with this in mind would be misled to think he hadn’t addressed the topic.

In short Westerholm, like Barclay, is quite selective in his description of what Sanders says. He lists only one of three different explanations Second Temple Jews gave for why they thought God elected them and rescued them from Egypt. He completely ignores Sanders’ quotes specifically addressing what they believed of their worthiness before God.

1. Second temple Jews held together God’s grace and works. Paul by way of comparison considered God’s grace antithetical to human works.

Westerholm’s basic problem, the reformers basic problem, was failing to distinguish between ‘works of law’ (Gal 3.2-5, 10; 5.4) and ‘good works’ (Gal 5.5-6, 19-21; 6.7-10) in Paul’s thought.

It’s obvious Paul has different understandings about what the Gentile believers should and should not observe. They should not observe the works of law or come under the law of Moses. But they should fulfill the law in love, resist various sins and do good to reap eternal life.

In short, Paul does consider God’s grace antithetical to the works of law and the law of Moses. But he does not consider God’s grace antithetical to acts of love, observing prohibitions of sin, and doing good to receive eternal life.

3. For Paul, God’s gift of salvation necessarily excludes any part to be played by God-pleasing “works” since human beings are incapable of doing them.

Sanders argued of the Jews;

As long as one believes that (whatever is to be said of Gentiles) Jews will be “saved” provided they show a basic willingness to comply with the laws of the covenant (some Jews set the standard higher than that; but some did not), one will naturally believe them capable of showing at least the required modicum of obedience.

And that Paul was like this also. Westerholm does not believe anyone is capable of the modicum of obedience. In this he does not make a distinction between sinners and the righteous.

I agree with Westerholm the salvation of sinners necessarily excludes any part played by them by God pleasing works because they are incapable of doing them.

However I also believe sinners are saved by grace are no longer sinners. They have become righteous and Paul thinks of them as saints, expecting them to live accordingly. God’s grace is both effectual and has expectations of reciprocity (Eph 2.8-10; Gal 5.5-6; 1 Cor 7.19; Rom 2.26-29; 6.17-18; ).

Paul expected believers to maintain a modicum of obedience and understood God’s grace was the driving force for it (Phil 1.3-6; 2.12-13). Paul also says they will be judged accordingly. Like the Jews Paul does say the final judgment will be according to good works (Rom 2.6-11; Gal 6.7-10; 2 Cor 5.9-10; Eph 6.5-8).

Westerholm once again advocates a miserable sinner understanding of Christianity which Paul does not hold. I think he has a wrong understanding of Paul’s expectations for how Christians will live when they are powered by God’s Spirit and grace.

Are “Sinners” All That Sinful? (Against Räisänen)

In this chapter Westerholm considers an argument put forward by a Pauline scholar named Heikki Räisänen. Räisänen did a study on how consistent or inconsistent Paul’s theology was.

Heikki Räisänen’s Paul and the Law set out to prove that the apostle Paul was never so afflicted. That, at least, is a positive spin on its agenda. Räisänen himself put the matter somewhat differently: “contradictions and tensions have to be accepted as constant features of Paul’s theology of the law” (11). He proceeded to explore Paul’s thinking on five topics with this agenda in mind.

Our concern here is with the third: the apostle Paul believed that human beings untransformed by the gospel of Christ both can, and cannot, do what is good. (35)

A key point to recognise in Westerholm’s argument is that here he explicitly refers to untransformed humans. He is not talking about believers in Christ.

Human Inability to Do Good

The simplest part of my task is documenting the Pauline conviction that untransformed human beings—human beings “in Adam,” or “in the flesh,” to use Paul’s terminology—cannot do what is good. (36)

To show this Westerholm walks us through several passages in Paul. From Rom 3.10-18 Westerholm shows there is no one who does good.

He then looks at Rom 7.7-25 and notes there are varied interpretations of the passage. From his other book I know he sides on thinking Paul is not referring to his Christian life. In this section he uses the passage to highlight Paul’s understanding of humans prior to conversion, which he points out is even more true if Paul was referring to his Christian life. I’ve posted on this passage here (Link).

From Rom 8.5-8 Westerholm notes Paul’s in the flesh references (cf. Gal 5.17, 19-21). In a few passages Paul makes comparisons between those in the flesh and those in the Spirit. Unbelievers are in the flesh. Transformed believers are in the Spirit.

Finally he considers Rom 5.19; 6.1-2, 16-23 briefly.

Humanity Does Good

Paul certainly believes that human beings have an awareness of the good they ought to do. Admittedly, what is perhaps Paul’s most explicit statement to this effect gives us no reason to think human beings ever act on that awareness (38)

Westerholm reviews Rom 1.28-31, 1 Thes 4.12, Rom 12.17 (cf. 2 Cor 8.21), Rom 14.18, Phil 4.8 and 1 Cor 5.1 to prove his point that unbelievers have some awareness of right and wrong.

He then looks at Rom 2.14-15, Rom 2.25-27 and Phil 3.6. Regarding Rom 2.25-27 Westerholm thinks Paul is raising a hypothetical as if it couldn’t happen, I disagree with Westerholm because Paul is echoing Eze 36.25-27 here in light of Gentiles coming to faith. This is no mere hypothetical.

Lastly he quotes Rom 13.1-4. By instructing his Roman Church to submit to their secular authorities Paul says they recognise good and evil conduct and dispense justice accordingly.

Augustine, Luther, and Calvin

Westerholm considers several quotations from Augustine, Luther and then Calvin to show they each rejected the idea that untransformed humans could do any good.

Augustine emphasises the need for having experienced God’s love in order to perform any righteous act.

Both Luther and Calvin further prioritised the need for faith before God could look upon any work with favour.

Paul Reconsidered

Westerholm’s summarising position is;

If the most fundamental responsibility human beings have pertains to their relationship to God, then any claim to virtue is vitiated when that relationship is not in order. So thought Augustine, Luther, and Calvin. Are there grounds for believing Paul thought so too? (48)

He quotes from Paul and other scripture (Rom 1.21; 14.23; Mt 7.17-18) to prove his point.

My Response

Aside from a few details, I’m in general agreement with Westerholm’s argument in this chapter. I’m not a pelagian.

Justified by Faith (Against Wright)

This is probably his longest chapter in the book. I have to be brief in describing it. I’ve tried to give a good description of the overall content. But I haven’t been able to describe everything.

In his earlier book (Perspectives Old and New on Paul) and in trying to explain the difficulty of translating the various Greek ‘dika’ cognates. Westerholm explains why he created the words “dikaiosness” and “dikaiosify” to help communicate his understanding of righteousness. He says he meant it as a joke and people were not meant to take it seriously. While accounting for this ‘painful experience’, he refers to the earlier argument as a foundation for this chapter and says Wright’s views are to be taken seriously.

Righteousness in Wright

In the first half of this section Westerholm outlines Wright’s overview of scriptures narrative within which he situates his reading of Romans 1-4 and his understanding of righteousness. Westerholm also notes Wright’s interpretation of pistis Christou (Rom 3.22).

Westerholm then hones in on Wright’s understanding of righteousness as understood within the law court. He quotes Wright saying righteousness is not a moral righteousness, it’s the status of the person whom the court has vindicated.

For Wright, justification has Law court, Covenant and Eschatological connotations. In summary he quotes Wright again;

Righteousness, dikaiosynē, is the status of the covenant member. … [It is] the status of “having-been-declared-in-the-right,” is the implicit metaphor behind Paul’s primary subject in this passage, which is God’s action in declaring,

“You are my children, members of the single Abrahamic family.” (58-59)

I’ve reviewed one of Wright’s books here (Link). Westerholm seems to have understood him well enough.

Righteousness in the Old Testament

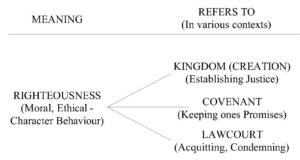

Westerholm’s task in this section is to decide whether Wright’s understanding of righteousness corresponds with Paul’s. Westerholm is also looking for a definition (meaning) of righteousness that fits every single instance of righteousness in the scriptures.

Westerholm then quotes Gen 6:9; Job 27:17; Ps 33:1; 7:8 making his point. Each of these demonstrate righteous behaviour. He then lists Gen 18.25; Ps 1.6; 34.15-16; Eze 3.20; 18.5-9 which contrast the righteous with the wicked.

The “righteous” are thus those who do what they ought to do (i.e., righteousness). (61)

Human beings, as human beings, have moral choices to make. They ought to make the right ones; they ought, in other words, to be “righteous.” (63)

He reviews some more passages about righteous weights (Lev 19.35-36), rules (Dt 4.8) and paths (Ps 23.3).

So far, the truth seems trite enough. But its implications, in the context of the present debate, are crucial: for starters, the language of “righteousness” can hardly designate membership in God’s covenant people. (61)

In trying to ram home this point, Westerholm reviews a number of texts describing people as righteous which he believes are outside any covenant (Dt 9.6-7; Gen 6.9; 7.1; Gen 18.22-33) He shows a few passages where people question whether anyone can be righteous (Job 15:14–16; 25:4–6; Ps 143:2; cf. Job 4:17–19).

Covenant membership is not, for scales, paths, or commandments, a live option; but they ought to be “righteous. So “righteousness” does not mean, and by its very nature cannot mean, membership in a covenant. Likewise, it does not mean, and by its very nature cannot mean, a status conveyed by the decision of a court. (64)

Basically Westerholm is testing whether Wright’s understanding of the judges verdict of righteousness within the law court setting fits every single instance of righteousness in scripture. Unsurprisingly it doesn’t. He says in law court scenes judges are required to judge people and determine if a particular deed they have done is righteous or not.

Righteousness in Paul

Westerholm begins by quoting a number of references in Paul about right which describe moral qualities including people’s behaviour (1 Thess 2.10; Rom 6.18; 7.12; Phil 4.8; 2 Cor 6.14; Rom 6.19; 1 Cor 4.4; Rom 2.13). From these references he says of Paul,

the use of righteousness terminology to designate the moral behavior required of human beings—all human beings, inside or outside “the covenant” (66)

Note that his rejection of this kind of behaviour is independent of whether or not the people are in a covenant or not.

Westerholm gives a brief reading of Romans again. He focuses on Paul’s description of the human plight (Rom 1.18-32; 3.10-18; 4.5). After quoting Gal 2.16 and Rom 3.20-22 and noting their similarity, Westerholm ridicules Wright.

Westerholm’s basic understanding of justification is that God “justifies,” finds “righteous” or “innocent,” those who are not; he judges the unrighteous as though they were righteous. He bases this on (Rom 4:5; 5:6–9; cf. Ps 143:2 Rom 3:20–22; Gal 2:16). He then gives an explanation of how God can still be described as righteous when he does this. The explanation involves his reading of Rom 3.25-26 and a description of Christ’s sin atoning death.

Westerholm weighs in on the varieties of interpretations for Paul’s expression ‘righteousness of God’. Finally he begins to round up with his main point.

What remains to be underlined, however, is that it is sinners who believe whom God declares righteous. … for Paul, where divine grace is involved, human achievement cannot be a factor (Rom 11:6). (71)

Westerholm uses Rom 3.22, 24; 4.4-8, 16; 9.31; Eph 2.8-9 to try and prove his point. Many of his passages refer to initial salvation, not future judgment and salvation. He finishes this chapter saying,

The upshot of our discussion is nonetheless that Paul’s doctrine of justification means what Augustine, Luther, and others have long taken it to mean: only by faith in Jesus Christ can sinners be found righteous before God. (74)

My Response

Imagine having to come up with an expression or definition trying to capture multiple connotations associated with a term used throughout scripture? Would you hone in on one or two associations and ignore the rest? Or would you try and give an expression that embraced most of what you see?

Or, what would say is the difference between the meaning of a word and its significance? The difference between meaning and significance is like the difference between a word and a symbol. The word has a precise meaning. The symbol stands for something and can actually be more powerful than some words. For example, the word cross means two intersecting lines. But The Cross has a great deal more significance.

I think Westerholm gets the meaning of righteousness right. But I think Wright has a better understanding of the significance of righteousness in Paul’s thought. Wright’s understanding is broader and makes sense of much more of what Paul says than Westerholm’s narrow definition.

I referred to them previously but my readings of Romans 1-4 and Galatians have positions built in them overcoming several of Westerholm’s objections.

In what follows I will respond to his more significant criticisms of Wright’s covenantal understanding of righteousness.

General Meaning and Specific Usage

I’m in agreement with Westerholm about the root meaning of the ‘righteousness’ word group. As I have mentioned in my series on righteousness, the word is commonly used to denote the identity, character and behaviour of a group of people. So yes, righteousness is ‘doing what is right’ or what people ‘ought to do’ is a fair description.

But, I also note that it’s possible for a word to have a general meaning, which can be employed in different contexts in specific ways. With respect to righteousness and in addition to the ethical aspects I identified three. Kingdom (Ps 22.28-31; 99.1-4), Covenant (1 Sam 12.6-8; Dt 6.24-25; cf. Dt 5.1-3; Lev 26.14-15) and Law Court (Dt 16.18-20; Lev 19.15-16).

Westerholm is insistent that righteousness can only have an ethical meaning and that involves doing what one ought to do. He does not seem to have considered the specific usage of the word in different contexts. In particular he does not acknowledge where God in keeping his covenant promises is described as righteous. Nor does he note the covenantal context of commands in the law of Moses and the covenantal implications for their transgressions.

Outside the Covenant?

In a couple locations Westerholm is insistent that people are called righteous inside and outside covenants. He makes the point that if people are regarded as being righteous outside a covenant, it can hardly refer to covenant keeping or behaviour. In particular he lists Noah, the righteous in Gen 18 and references in Job.

If one were to ask Michael Horton, Meredith Kline or James Jordan they might start speaking various forms of covenant prior to the Mosaic covenant and suggest a person’s righteousness has covenantal significance. Hos 6.7; Dt 5.2-3; Heb 11.13, 39 make these points. All the righteous are beneficiaries of God’s covenant promises and will inherit the kingdom to come. If this is true they are within a covenant. Westerholm is wrong to assume there are righteous outside of a covenant relationship.

Are the righteous the People of God?

In a few locations, after quoting Wright, Westerholm rejects the idea that justification declares a person to be one of God’s people. If we look at scripture we see the righteous are described as;

- God’s people (Ps 14.5-7; 94.14-15; 125.2-3; Lk 1.75-77; cf. Ps 106.3-5; Isa 26.7-11; 32.16-18; 56.1-3; 60.20-21),

- God’s nation (Ps 33.1,12; Isa 26.2; 58.1-2; cf. Je 31:23),

- God’s servants (Ps 34.21-22; Mal 3.17-18), and

- God’s saints (Ps 31.18,23; 37.27-31; 97.10-12; Rev 19.8).

Westerholm is wrong to deny that the righteous are God’s people. Clearly you can see from each of these ‘the righteous’ are clearly God’s chosen people. The corporate designation ‘the righteous’ is virtually synonymous with God’s people. Taken further justification can be seen as the identification of one of God’s people.

Covenant Family

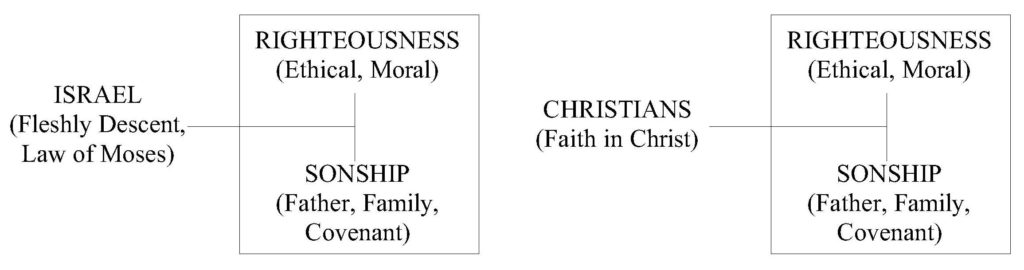

The biggest problem I see with Westerholm is that he does not see the relationship between righteousness and sonship. The apostle John and Jesus could not be clearer (1 Jn 3.7,10; Mt 13.43). Westerholm quotes 1 Jn 3.7 but fails to see the pairing.

Sonship is at times, synonymous with righteousness. Weights and rules cannot be God’s sons, but the righteous are. The ethical and familial associations are bound together in the one concept (e.g. Lk 3.7-8; 1 Pet 1.16-17). This brings us to Paul.

There is a stream of thought within covenant theology where covenants are said to form familial bonds. Think of marriage as a covenant bond which makes a husband and wife, family. Similarly, because God made a covenant with Abraham, Israel is now his son (Ex 4.22-23; Dt 14.1; Hos 11.1). Scott Hahn is one advocate of this. He argues a covenant is a means of establishing a kinship relationship between two parties. See my review of his book.

We should keep this in mind as we read Rom 4.9-12. Paul says, ‘the purpose was to make him the father’. What did God do that made Abraham the father of all who believe without being circumcised? God counted his faith as righteousness prior to his circumcision. This counting of righteousness established his fatherhood over all who would believe. Jews and Gentiles. They would be counted righteous and as his offspring because of their faith.

Likewise In Galatians (Gal 3.5-9). ‘Sons of Abraham’. Paul is explicit that those of faith are the sons of Abraham. Just as faith confers righteousness, so to does faith confer sonship in Paul’s thought. For him, the two are synonymous. ‘Justify the Gentiles by faith’. As with Romans above. Here we see righteousness is virtually synonymous with sonship.

As I mentioned before traditionally, Israel was considered God’s son. In Romans 9, Paul acknowledges this by saying they were adopted (Rom 9.4-5). He implies, that just as righteousness is now counted to Jews and Gentiles who believe, so is being one of Abraham’s offspring counted to Jews and Gentiles (Rom 9.6-8).

‘Counted as offspring’. What we see in english as ‘counted’ is in the Greek λογίζεται and is transliterated ‘logizetai’. I wrote a post on Paul’s use of this verb in Romans 4. Just as Paul uses logizetai to describe God regarding Abraham’s faith as righteousness. So to does he use the verb with respect to Abraham’s offspring.

I’m not denying the ethical and moral overtones associated with righteousness or its general meaning. I’m adding to that understanding, saying that in some contexts the ethical and familial connotations are inseparable and in Paul the familial connotations are quite important.

The significance of righteousness

Why is the counting of righteousness and therefore being one of Abraham and God’s children so important to Paul?

16 The Spirit himself bears witness with our spirit that we are children of God, 17 and if children, then heirs—heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ (Rom 8.16-17)

A person could be sinless and perfectly righteous, but that would never grant them the blessings that only come to those within the family. A father does not give his blessings to anyone who happens to be morally good or righteous. He only passes them on to members of his family. In this case his children. Because children are their parents heirs, they inherit. Think of the inheritance given to sons.

Paul normally says the unrighteous will not inherit the kingdom of God (1 Cor 6.9-10; Gal 4.30; 5.21; Eph 5.5; Col 1.12). The reverse must be true, only the righteous can inherit the kingdom of God. Westerholm notes the distinct moral themes in some of these passages but misses the familial overtones associated with inheriting.

In Paul’s own words those of faith are sons of Abraham, sons of God even. In Paul’s own words the counting of righteousness by faith establishes Abraham as the father of all who believe, uncircumcised (Gentiles) and circumcised (Jews). One way of understanding justification then is that God is forming a new family and these are Abraham’s sons, God’s sons. These are part of the covenant (Gal 3.14, 16).

16 Now the promises were made to Abraham and to his offspring. (Gal 3.16)

A person could be sinless and perfectly righteous, but that would never entitle them to the blessings that only come to members within the covenant. God didn’t make promises to anyone who happened to be morally good or righteous. He only passes them on to those in the covenant. In this case Abraham and his offspring.

In Paul’s own words the promises were made to Abraham and his offspring. This is why for Paul it is critically significant that justification establishes believers within the Abrahamic family. That is the only thing which makes them beneficiaries of the covenant promises and blessings given to Abraham and his offspring.

This is the significance associated with the counting of righteousness that Wright has picked up on.

Redemption and the Blessing of Forgiveness

As Westerholm has rightly noted, Romans says a whole lot about sin (Rom 1.18-3.20), atonement through Christ’s death (Rom 3.25) and the blessing of forgiveness given to those whom God counts righteousness apart from works (Rom 4.6-8).

Okay, so can atonement and forgiveness fit into a covenantal framework? I should hope so, we have the historical example of the Passover, Israel’s exodus from Egypt and the giving of the law of Moses which includes a means of atonement and forgiveness (Ex 2.23-25; 4.22-23; Mt 26.26-28; Heb 9.15).

If we consider Paul’s statement about Christ’s death in Rom 3.23-25 I think Westerholm and Wright are in agreement regarding the sin bearing consequences of Christ’s death. But Wright puts Christ’s death, which certainly deals with moral issues, within a covenantal narrative. As does Jesus and the author of Hebrews.

The blessing of forgiveness is also given to those within the Mosaic covenant (cf. Lev 1,4-5,16). In Rom 4.6-8. Paul is echoing Psalm 32. Now blessings are certainly part of covenants (e.g. Dt 28) and we should note Psalm 32 also refers to God’s steadfast love which is commonly known as His covenant faithfulness towards his people. Again there are moral and covenantal overtones to the blessing of forgiveness given to those whom God counts apart from works.

Conclusion

Westerholm is right to highlight the very moral overtones in Paul’s justification writings. But he does not acknowledge the familial and therefore covenantal associations. Wright possibly makes the opposite mistake not focusing as much on the moral issues as he should, but overall I think he makes sense of more of the scriptural data, linking it all together as bible scholars ought to do.

The upshot of our discussion is nonetheless that Paul’s doctrine of justification means what Barnabas, Justin Martyr, and others have taken it to mean: by their faith in Jesus Christ, Gentile believers are regarded as in God’s family and heirs of the covenant.

Not by Works of the Law (Against Dunn)

Westerholm begins by telling a good joke. He then introduces Luther, his reading of Galatians, works of law and good works. In this chapter he seeks to defend Luther’s generalisation of works of law to include good works and rebuff Dunn’s definition of works of law as boundary markers.

To be sure, the moderns have rightly portrayed the situation that occasioned Paul’s justification formula (“not by works of the law, but through faith in Jesus Christ”). And certainly that formula was meant, in the first instance, to counter any suggestion that Gentile believers should be circumcised. But what Paul had in mind when he mentioned “works of the law” was, I believe, closer to (though not identical to) Luther’s “good works” than to Dunn’s “boundary markers.” (77)

The Law and Its “Works”

Westerholm begins his argument quoting Ps 143.2 again emphasising human sin and inability to be righteous. He argues justification is not possible for anyone living under the terms of the Mosaic law and covenant. He then argues that Paul uses the terms works of law and law interchangeably.

The (impossible) justification by “works of the law” (2:16) is thus no different from the (impossible) justification by means of “the law” in 2:21 and 5:4. What make “works of the law” and “the law” so interchangeable?

Both refer, in these passages, to the divine commandments given to Israel at Mount Sinai; and commandments, by their very nature, require “works” that fulfill them. Simply put: inherent in any law is the obligation of its subjects to comply with its terms. …

This fundamental principle of the law is, moreover, what, in Paul’s argument, distinguishes God’s law from God’s promise: a blessing promised by God, unlike one attached to a law, is not conditional upon human obedience (78-79).

Westerholm argues the law cannot serve as the path to righteousness.

The Law and Righteousness

Looking to Rom 2.7-13, Westerholm argues doing good is the same thing as doing the law.

Paul goes on immediately to equate those who, according to 2:7 and 10, do “what is good” and will be given eternal life with those who are “doers of the law”: “It is not the hearers of the law who are righteous before God, but the doers of the law will be justified” (2:13). To “do the law” is to do “what is good.” (80)

As we have seen, to be justified as a doer of the law (2:13) is no different from being granted eternal life because one has persisted in doing what is good (2:7, 10). To deny, then, that one can be justified by “works of the law” is, essentially, to deny that one can be justified by doing good. (83)

He defends the law and says it is good. It’s just that humans are sinful and can never be righteous on its terms. From this it follows to Westerholm “a person is not justified by works of the law.” (82)

Westerholm voices his problems with the reading of Rom 2.6-11 that says believers will be judged according to their works and this is what decides their eternal destinies. He thinks Rom 3.20 effectively rules out the possibility because it refers to ‘no flesh’.

But where the call of God in the gospel leads to faith, a new work of God has begun. Westerholm ends on a more positive note on his expectations for what a believer’s life will look like.

My Response

As with previous chapters, Westerholm wrongly assumes justification only signifies a sinner being declared righteous when they are first converted. He does not recognise Dunn and Paul refer to the identification of existing Gentile believers as righteous. Like before he still continues with a miserable sinner understanding of Christianity. Assuming righteousness means sinless perfection, only recognising the sin and neglecting the good.

Westerholm says, justification is not possible for anyone living under the terms of the Mosaic law and covenant. Luke and many other scriptures say otherwise (e.g. Lk 1.5-6). People in the OT were recognised righteous even though they were under the law. The righteous exist. The two questions which follow are:

- How they became righteous? And then,

- How you can tell they are righteous?

The law of Moses did not make them righteous in the first case, neither according to Paul are the ‘works of law’ the means by which they were identified.

Using Ps 143.2 Westerholm denies anyone is righteous. Westerholm fails to note that in Gal 2.16 Paul says ‘by works of law’ no one will be justified. This excludes ‘works of law’ from justification, but leaves open ‘words’ and ‘good works’ as argued by Jesus (Mt 12.37) and James (Jas 2.21-25). In Rom 3.20 Paul says ‘no flesh’ shall be justified in his sight. Westerholm believes this refers to all humanity. No. Paul distinguishes between those in the flesh and those in the Spirit (Rom 8.9). Those of the Spirit are righteous, in Rom 8 Paul refers to them as ‘sons of God’, and you can tell this by some other means.

Westerholm’s understanding of what Paul means by the law is sloppy. Have a look at my series on the law to understand why. Or have a look at Brian Rosner’s work on Paul and the Law, Keeping the Commands of God. Westerholm groups several understandings together as if they are the same thing.

The supposed interchangeability between ‘works of law’, ‘the law’, those who ‘do good’ and the ‘doers of the law’ drives Westerholm’s reading. The distinctions drive mine. Paul is very clear in Galatians that relying on ‘works of law’ they are in danger of falling from grace (Gal 5.4). Yet in the same letter Paul is insistent they they need to avoid various sins (Gal 5.19-21) and do good (Gal 6.6-10) both with soteriological consequences. Paul is against the imposition of ‘works of law’ on Gentiles, but is insistent all believers should be told to devote themselves to good works (Tit 3.8,14). Luther and Westerholm were wrong. Paul sees a difference between ‘works of law’ and ‘good works’.

Justification and “Justification Theory” (Against Campbell)

In this chapter Westerholm gives a brief assessment of Douglas Campbell’s massive book, ‘The Deliverance of God, An apocalyptic re-reading of Justification in Paul. Fortunately I’ve read the book. Westerholm first sets out to describe Campbell’s ‘Justification Theory’.

“Justification Theory”

In justification theory, God is depicted as an enforcer of retributive justice, not love. Justification theory emphasises an individualist, conditional, and contractual view of salvation.

Under the first contract posited by justification theory, the condition for God’s approval and eternal life is generally seen as ethical perfection.

Sinful man is depicted as rational and has the ability to realise he cannot be perfect and thus his plight before an angry God.

The second phase of the model focuses on the death of Christ and the decision to trust and put one’s faith in God rather than try and be perfect.

Faith and works are seen as contractual options the rational man is able to choose from in order to gain God’s approval and eternal life.

But this is not Campbell’s understanding of Paul.

The real Paul, according to Campbell, is not the proponent of “justification theory,” but the apostle of apocalyptic redemption—defined, point by point, by way of contrast with the rejected theory. Campbell’s alternative falls outside the scope of our study. …

Among his most basic reasons for depicting the two schemes as mutually exclusive is the view of God he believes to underlie each: “the God of Justification is just but the God of the alternative theory is benevolent. Fundamentally different notions of God are in play” (89).

Westerholm’s goal is not to evaluate Campbell’s claims about the inadequacies of the theory, but to ask whether, or to what degree, Paul’s understanding of justification corresponds with it. Campbell thinks justification theory is not Paul, Westerholm thinks it is.

The Goodness of Creation—and the Moral Order

Westerholm’s response doesn’t really engage with Paul or any other. Rather he comments on the goodness of God’s creation and how sin mars its beauty. He argues God must step in to restore his good creation and deal with sin.

These are not the demands of a code arbitrarily prescribed and optional in its enforcement. They are the conditions of living in, and maintaining, a rightly ordered cosmos. The law that spells out, for the benefit of human beings, such appropriate behavior is both right and good. Conversely, sin is not simply the transgression of a code, but the violation and marring of creation’s goodness. A god who chose to overlook the disfigurement of a good creation would be neither good nor just. (91)

The Goodness of Justification

In this section Westerholm just repeats again his understanding of Justification by stepping through some verses and passages in Romans 1-4.

Justification is but one of the ways in which Paul pictures the salvation and transformation of Adam-like human beings, but it must be allowed its place with the others; people have not lived as they ought, and the “unrighteous will not inherit the kingdom of God” (1 Cor 6:9). But God shows himself both good and just when, because Christ’s death bore the bane of humanity’s sins, he finds believers righteous (94).

My Response

Campbell’s ‘Justification Theory’ (JT) is really his depiction of the reformers reading of Romans 1-4. I’ll walk you through his basic line of thought in his book.

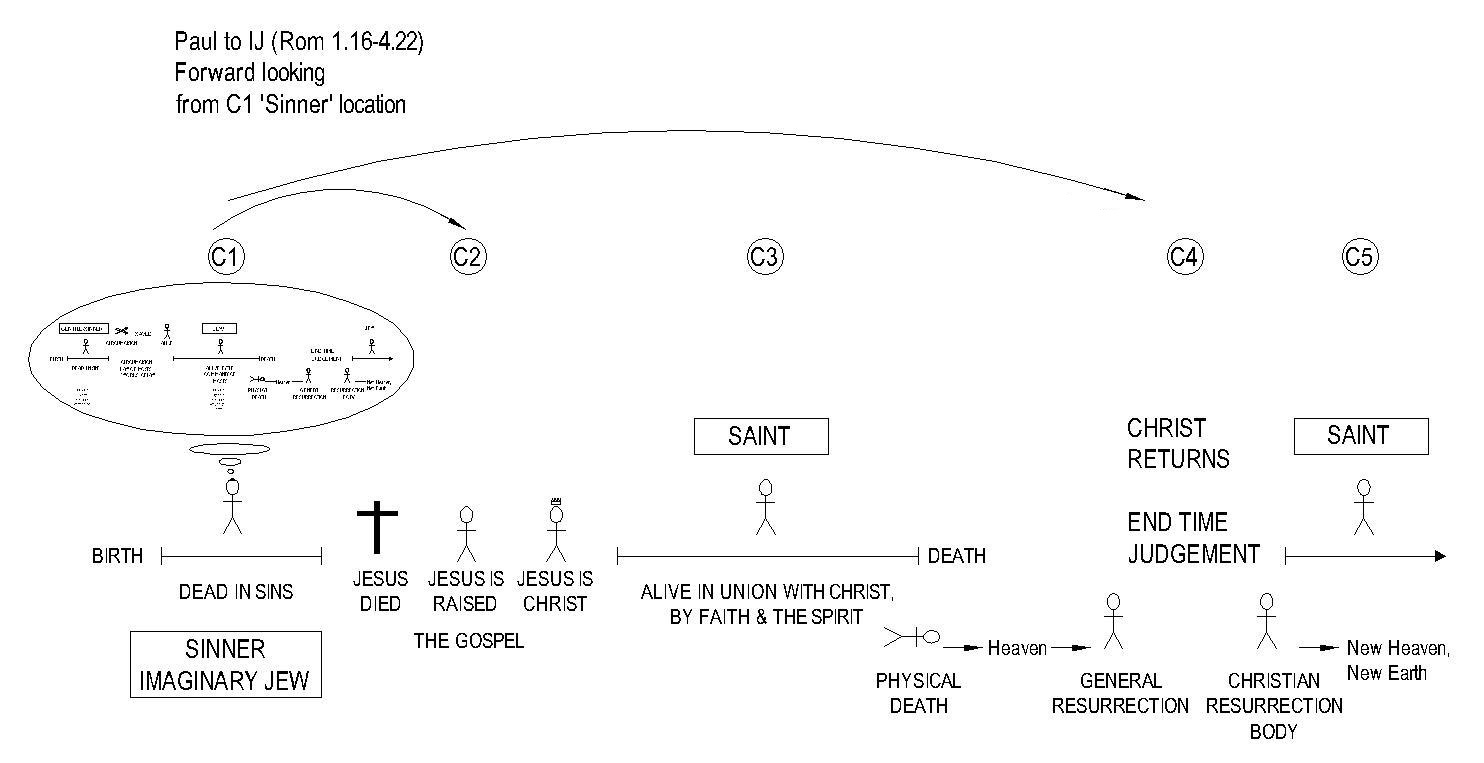

Westerholms depiction of JT is a fair. In Romans 1-4 We should note the strong forward moving progression of thought from sin, to realisation of the problem, to despair about the problem, to seeking for a remedy, which can only be found by putting faith in Christ. He thinks of this as forward moving, because it always starts from a point of a problem which requires a solution.

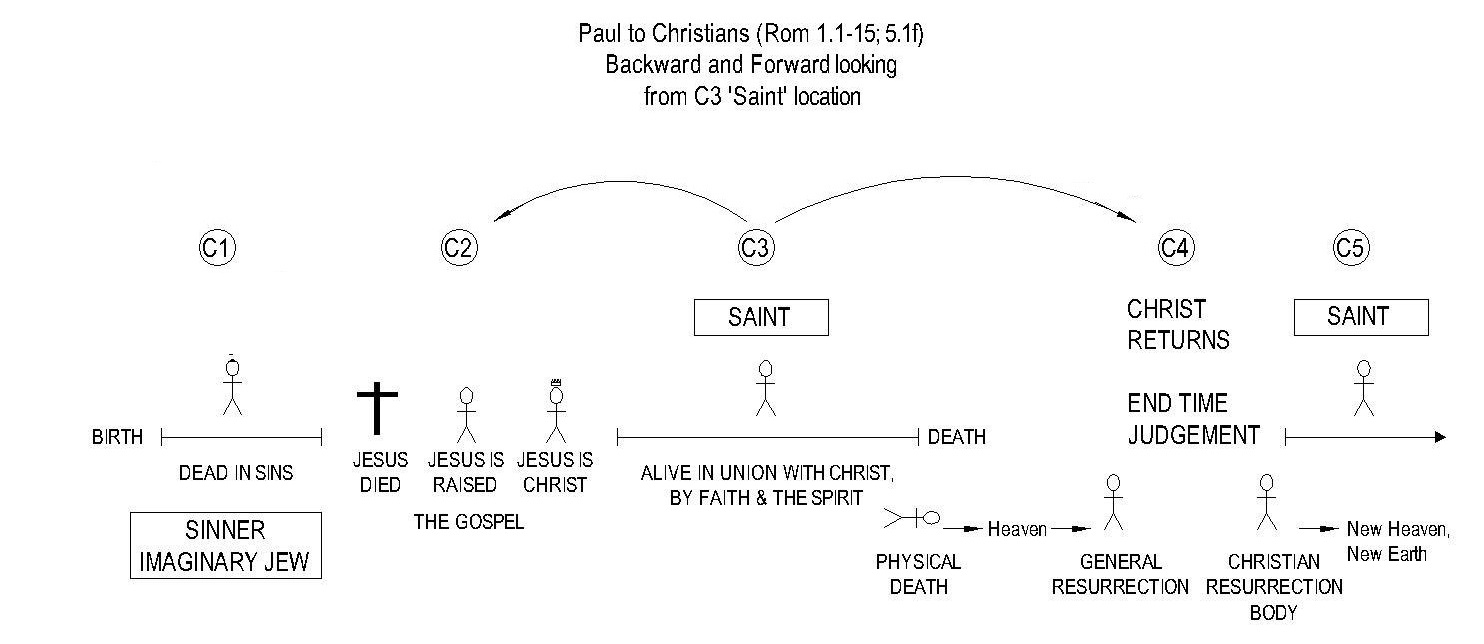

Campbell then reviews what Paul says in Romans 5-8. Paul assumes in Romans 5-8 that he and his audience have been delivered from the dark situation they were in. Paul’s whole way of thinking is now shaped by God’s love and it looks backward to their former state and what God has done to save them from it.

He concludes Paul’s theology is framed from a saved perspective. Their understanding of God’s retributive justice and wrath, what their plight was before God and their initial salvation is retrospective.

The reason for the difference in forward and backward perspectives is that Rom 1.18-32 isn’t Paul’s argument.

In Romans 1-4 Paul is speaking to an imaginary Jewish (IJ) interlocutor (Rom 2.1-5, 17, 25-29; 3.1-10, 27-31; 4.1). Campbell argues Rom 1.18-32 is a big example of ‘prosopopoeia’ or speech in character. All this stuff about God’s wrath, sinners as rationale beings, the protrayal of God as primarily retrobutive is not Paul’s theology. It’s IJ’s. He notes the diatribal exchanges throughout Romans which has been noted by scholars such as Stowers and Song.

Re-reading the forward looking framework of Romans 1-4 looks a bit like this.

Paul’s backward and forward looking framework in Romans 5-8 looks a bit like this.

I’ve gone into reasonable depth in my series (Dialogue with a Jew) determining whether Rom 1.18-32 is Paul’s or IJ’s argument and I think it’s both.

Which I have some agreement with Westerholm here, the chief problem I have with his argument is his assumption Romans 1-4 is Paul’s gospel, his omissions of the diatribal nature of Romans 1-4 and his assumption justification is only applied to sinners being converted, not the righteous being identified as righteous.

In a Nutshell

As one would expect this chapter briefly captures the essence of his previous chapters and repeats his main points.

In spite of recent challenges, I believe such an understanding of Paul’s doctrine of justification does better justice to the Pauline texts. …

But the doctrine of justification means that God declares sinners righteous, apart from righteous deeds, when they believe in Jesus Christ. (98)

My Response

In a nutshell:

Westerholm needs to review how he represents Paul’s gospel. Paul’s gospel concerns Jesus. He tells the story of Jesus, proving from the Old Testament scriptures that Jesus is the promised Christ. Preaching about God’s wrath and bringing his listeners to liminality is not part of Paul’s gospel message.

Westerholm adopts a miserable sinner understanding of Christianity. Paul is not like this. He affirms that some people are unrighteous and some are righteous. Good and bad. Westerholm portrayal of believers is unbalanced and does not match scripture. The indicative Paul holds of believers is that they are saints. He expects them behave accordingly. He expects a modicum of obedience. He knows his audiences will be judged accordingly.

Westerholm is very selective in his treatment of Second Temple Judaism and Sanders. He has completely neglected to acknowledge the rabbis portrayal of their own unworthiness before God. He has neglected to acknowledge Sanders pattern of Covenantal Nomism is now the benchmark for how most scholars understand Second Temple Judaism.

Westerholm is naive to assume Paul uses justification everywhere to denote the same thing. In some cases Paul does refer to the initial event where sinners are made righteous in God’s sight. But plays down the fact that justification can also function as the means by which people who are already righteous are identified as such.

Westerholm has missed Paul’s connection between righteousness and sonship. These two are virtually synonymous when it comes to how Paul views believers in Christ. Believers in Christ have Abraham as their father. They are his sons and God’s sons. Sonship comes with it all the blessings of family inheritance, God’s covenant promises and forgiveness. This means he rips justification out of the overall narrative of scripture in which God’s covenant and promises to Abraham are the prime vehicle of salvation for all nations.

Westerholm is wrong to assume the interpretations of Paul he is arguing against are new. In various forms they were articulated by the early church fathers. They represent a return to the earliest articulations of justification we have.

Recommendation

I wrote a small series on what I call explanatory functions. In it I put forward the suggestion that different groups over time tend to interpret scripture through what I call an ‘explanatory function’.

Westerholm’s view is what I call the Old Perspective on Paul. He is arguing – within his perspective and for his perspective – using all the hallmarks of Lutheran theology.

Stendahl, Sanders, Wright and Dunn are the early runners of the New Perspective. They seek to correct and improve this Old Perspective with better readings of Paul which account for a greater range of biblical texts.

What we see in this book is a clash of different framings of Paul and how justification fits within those framings. Westerholm’s argument is not the last word in the debate. But his arguments present the majority position in protestant churches to date. His arguments in this book put together in a small book the best arguments so far for sticking with the Lutheran – reformed interpretation.

As you can see I found many of his arguments unconvincing. Biblically or historically.

I recommend this book especially for proponents of the New Perspective. This book has been written with the wider populace in mind. That means a lot of people have probably read it.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2017. All Rights Reserved.