It is essential for a Christian, to find out whether the [human] will does anything or nothing regarding eternal salvation. This is the primary issue between us [Erasmus & Luther], the point on which everything in this controversy turns.

For what we are doing is to inquire what free choice can do, what it has done to it, and what is its relation to the [Sovereign] grace of God.

If we do not know these things, we shall know nothing at all of things Christian, and shall be worse than any pagan. … It therefore profits us to be very certain about the distinction between God’s power and our own, God’s work and our own, if we want to live a godly life. (Luther, Bondage of the Will)

- Link: Amazon

- Length: 142

- Difficulty: Medium

- Topic: Theology, Divine Sovereignty and Human Responsibility, Salvation

- Audience: Educated Christians

- Published: 1525

In 1524 Desiderius Erasmus (a Dutch Renaissance humanist and Catholic priest during the reformation) wrote a letter to Martin Luther arguing for the freedom of the Will. Luther responded in 1525 writing his argument titled in the opposite, the ‘Bondage of the Will’.

Bondage of the Will is one of Luther’s most significant and well known writings.

Today there seem to be several translations of Luther’s letter. Some of which are public domain (here, here and here) and some are more readable than others. I purchased the Bloomsbury copy for its readability and also read through a commentary of it by Gerhard Forde, who seems quite enamoured by Luther. Forde quotes extensively from Packer’s translation.

Today there seem to be several translations of Luther’s letter. Some of which are public domain (here, here and here) and some are more readable than others. I purchased the Bloomsbury copy for its readability and also read through a commentary of it by Gerhard Forde, who seems quite enamoured by Luther. Forde quotes extensively from Packer’s translation.

As with all theologians, what they say needs to be weighed against scripture and not blindly accepted. I’ll walk us through some significant elements of the letter, following Forde’s structure and provide comment afterwards.

This post is one of my book reviews.

Contents

Main points

Argument about Scripture

At the beginning of his Letter Luther explains why he took a while to respond to Erasmus. He felt like he and Melanchthon had already answered his arguments in other writings and found it beneath him to respond.

I have already often refuted them myself. And Philip Melanchthon has trampled them underfoot in his unsurpassed book Concerning Theological Questions. His is a book which, in my judgment, deserves not only being immortalized, but also being included in the Church’s canon, in comparison with which your book is, in my opinion, so contemptible and worthless that I feel great pity for you for having defiled your beautiful and skilled manner of speaking with such vile dirt.… To those who have drunk of the teaching of the Spirit in my books, we have given in abundance and more than enough, and they easily despise your arguments. (Desiderius Erasmus and Martin Luther, Discourse on Free Will, ed. and trans. Ernst F. Winter, Bloomsbury Revelations (London; New Delhi; New York; Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2013), 103–104.)

In this first section, while acknowledging some of Erasmus qualities, Luther describes Erasmus’ argument for free will to be ‘contemptible’, ‘worthless’ and ‘vile dirt’. Of his own teachings he says they are ‘of the Spirit’, which suggests he thinks his writings are inspired by the Holy Spirit, just like scripture.

From the outset, Luther continually ridicules Erasmus and displays a high opinion of his own writings. This tone and manner of dealing with his opponent is typical of the whole letter.

Erasmus argued that some truths of the bible ought to be kept from the general public because they may cause strife and harm people’s faith. Luther had the opposite view arguing that Christianity is made up of ‘assertions’ (propositional truth) and that Christ ought to be preached everywhere and all the time.

[Paul] would have the truth spoken everywhere, at all times, and in every way. He is even delighted when Christ is preached out of envy and hatred, and plainly says so. “Provided only that in every way, whether in pretense or in truth, Christ is being proclaimed” … Truth and doctrine should always be preached openly and firmly, without compromise or concealment … [629] … If we ask you to determine for us when, to whom, and how truth is to be spoken, could you give an answer?… Perhaps you have in mind to teach the truth so that the Pope does not object, Caesar is not enraged, bishops and princes are not upset, and furthermore no uproar and turmoil are caused in the wide world, lest many be offended and grow worse?… His Gospel which all need should not be confined to any place or time. It should be preached to all men, at all times and in all places. I have already proved above that what is written in Scriptures is plain to all, and is wholesome, and must be proclaimed abroad. (114)

Argument about God’s Sovereignty

With respect to Determinism and Free-will, Luther is very much an ‘either-or’ person as opposed to ‘both-and’. His understanding of God’s Sovereign will rules out the possibility of human free-will from the outset.

It is then essentially necessary and wholesome for Christians to know that God foreknows nothing contingently, but that he foresees, purposes and does all things according to His immutable, eternal and infallible will. This thunderbolt throws free will flat and utterly dashes free-will to pieces. Those who want to assert it must either deny this thunderbolt or pretend not to see it. (112)

and

From this it follows irrefutably that everything we do, everything that happens, even if it seems to us to happen mutably and contingently, happens in fact nonetheless necessarily and immutably, if you have regard to the will of God. For the will of God is effectual and cannot be hindered, since it is the power of the divine nature itself; moreover it is wise, so that it cannot be deceived. Now, if his will is not hindered, there is nothing to prevent the work itself from being done, in the place, time, manner, and measure that he himself both foresees and wills.

And lastly

I will not accept or tolerate that moderate middle way which Erasmus would, with good intention, I think, recommend to me: to allow a certain little to free will, in order to remove the contradictions of Scripture and the aforementioned difficulties. The case is not bettered, nor anything gained by this middle way. Because, unless you attribute all and everything to free will, as the Pelagians do, the contradictions in Scripture still remain, merit and reward, the mercy and justice of God are abolished, and all the difficulties which we try to avoid by allowing this certain little ineffective power to free will, remain just as they were before. Therefore, we must go to extremes, deny free will altogether and ascribe everything to God! (135)

Luther applies this understanding especially to those who will be saved. God is the one directing their thoughts and actions according to his sovereign rule to bring about their salvation.

Argument about our Willing

Where does this leave human free-will? Luther is a bit of a mixed bag here, providing several answers. He makes a distinction between

- everyday matters and

- moral choices and actions particular to salvation.

First the everyday matters.

But, if we do not want to drop this term altogether (which would be the safest and most Christian thing to do), we may still use it in good faith denoting free will in respect not of what is above him, but of what is below him. This is to say, man should know in regard to his goods and possessions the right to use them, to do or to leave undone, according to his free will. Although at the same time, that same free will is overruled by the free will of God alone, just as He pleases.

However, with regard to God, and in all things pertaining to salvation or damnation, man has no free will, but is a captive, servant and bondslave, either to the will of God, or to the will of Satan. (117)

He explains his understanding of how people choose and act according to salvation differently. This is the following quote which I hear is the most often quoted from Bondage of the Will.

He explains his understanding of how people choose and act according to salvation differently. This is the following quote which I hear is the most often quoted from Bondage of the Will.

Thus the human will is like a beast of burden. If God rides it, it wills and goes whence God wills; as the Psalm says, “I was as a beast of burden before thee” (Psalm 73:22). If Satan rides, it wills and goes where Satan wills. Nor may it choose to which rider it will run, nor which it will seek. But the riders themselves contend who shall have and hold it. … With regard to God, and in all things pertaining to salvation or damnation, man has no free will, but is a captive, servant and bondslave, either to the will of God, or to the will of Satan. (116)

Luther thus gives both God and Satan the power of necessity over the elect and reprobate respectively. This being said Luther also quotes Rom 1.18-19; 3.20 from Paul to the effect that sin in people (he makes no distinction between believers and unbelievers) renders them unable to choose or do anything good of themselves. People of themselves can only will and do evil. Only under the influence of God can they do good.

Now then, Satan and man, being fallen and abandoned by God, cannot will good, i.e., things which please God or which God wills, but are ever turned in the direction of their own desires, so that they cannot but seek out their own … So that which we call the remnant of nature in Satan and wicked man, as being the creatures and work of God, is no less subject to divine omnipotence and action than all the rest of the creatures and works of God. Since God moves and works all in all, He necessarily moves and works even in Satan and wicked man. But he works according to what they are and what He finds them to be, i.e., since they are perverted and evil, being carried along by that motion of Divine Omnipotence, they cannot but do what is perverse and evil. (132)

For Luther there is no distinction between the power of a believer or unbeliever to choose good and do good things. No one can.

Argument about Christ and Salvation

Luther applies the Divine Sovereignty – Free Will debate to God’s promises of Salvation. His logic is, if God’s promises were conditional on the decisions and behaviour of the elect then they could not be trusted. For Luther, God can only be trusted if his promises will come true regardless of how God’s people think and behave.

If God be not deceived in that which he foreknows, then that which He foreknows must of necessity come to pass. Otherwise, who could believe His promises, who would fear His threatenings, if what He promised or threatened did not necessarily ensue? How could He promise or threaten, if His foreknowledge deceives Him or can be hindered by our mutability? This supremely clear light of certain truth manifestly stops all mouths, puts an end to all questions, gives forever victory over all evasive subtleties (133)

Along the same lines, much of his reasoning comes down to assurance. For him if man is involved in the process of salvation then he can have no assurance of salvation.

As for myself, I frankly confess, that I should not want free will to be given me, even if it could be, nor anything else be left in my own hands to enable me to strive after my salvation. And that, not merely, because in the face of so many dangers, adversities and onslaughts of devils, I could not stand my ground and hold fast my free will—for one devil is stronger than all men, and on these terms no man could be saved—but because, even though there were no dangers, adversities or devils, I should still be forced to labor with no guarantee of success and to beat the air only. If I lived and worked to all eternity, my conscience would never reach comfortable certainty as to how much it must do to satisfy God. Whatever work it had done, there would still remain a scrupling as to whether or not it pleased God, or whether He required something more. The experience of all who seek righteousness by works proves that. I learned it by bitter experience over a period of many years. (138)

This position is intolerable for Luther. So he writes;

But now that God has put my salvation out of the control of my own will and put it under the control of His, and has promised to save me, not according to my effort or running, but … according to His own grace and mercy, I rest fully assured that He is faithful and will not lie to me, and that moreover He is great and powerful, so that no devils and no adversities can destroy Him or pluck me out of His hand … I am certain that I please God, not by the merit of my works, but by reason of His merciful favor promised to me. So that, if I work too little or badly, He does not impute it to me, but, like a father, pardons me and makes me better. This is the glorying which all the saints have in their God! (139)

My Response

Tone and Conduct

Luther’s general tone towards Erasmus is belligerent and insulting. Luther doesn’t hold back on his personal attack of Erasmus. This makes Luther appear quite arrogant and proud. This ought to function as a warning signal for problems in his theology.

I’ve often been told reformed theology should drive those preaching it to humility and love of others. Unfortunately with Luther this is not the case and makes me think the opposite. Erasmus once wrote of the Lutherans in his time;

I know nothing of your church; at the very least it contains people who will, I fear, overturn the whole system and drive the princes into using force to restrain good men and bad alike. The gospel, the word of God, faith, Christ, and Holy Spirit – these words are always on their lips; look at their lives and they speak quite another language. (“Letter of September 6, 1524”. Collected Works of Erasmus. 10. University of Toronto Press. 1992. p380)

Interpretation of Scripture

In his Diatribe, Erasmus argues for free-will using several scriptures. Some of these make it explicit people have some sort of choice, others imply a decision for good or evil by giving an instruction. Luther merely dismisses them and offers other interpretations. Some of his interpretations seem less plausible to me.

Luther as I have previously noted has a very high opinion of his writings, associating with them the same Spirit as scripture. Erasmus picks up on this when he says;

You stipulate that we should not ask for or accept anything but Holy Scripture, but you do it in such a way as to require that we permit you to be its sole interpreter, renouncing all others. Thus the victory will be yours if we allow you to be not the steward but the lord of Holy Scripture. (Hyperaspistes, Book I, Collected Works of Erasmus, Vol. 76, p204–05)

In Luther’s mind, only his positions on scripture have authority. He will not tolerate other interpretations. This means it probably doesn’t matter what the scriptures say, Luther’s interpretation is unfalsifiable and he will never be convinced otherwise. He has ruled out all other interpretations from the start.

Luther’s interpretations generally seems to apply a series of logical deductions which follow from the starting position of his doctrine of man and sin. While this may seem plausible, I find that his interpretations create unnecessary tensions with a number of scriptures which state some people are good and righteous, and especially final judgment texts. I think a better method of interpretation is to look at all scripture and determine a best fit for all. Not simply argue from a starting point and follow along a line on consecutive deductions.

Divine Sovereignty and Human Responsibility

As I mentioned previously, Luther is heavily in favour of Divine Sovereignty over Free-Will. He sees them in an ‘either-or’, rather than a ‘both-and’ relationship.

The ability to choose and decide between different options seems to be assumed by the following: Dt 25.1; 30.15,19; Jos 24.15,22; 2 Sa 24.12; Ps 119.30; Lk 23.24; Acts 20.16; Rom 14.13; 2 Cor 9.7. That God determines all things according to his sovereign will seems a given by: Job 42.2; Ps 135.6; Prov 16.4; 21.1; Rom 8.29-30; Eph 1.11-12.

My personal view is that the scriptures tend to reflect a both-and relationship between Divine Sovereignty and Human responsibility. Consider: Gen 50.20; Phil 2.12-13; 1 Cor 15.10.

In my page on Future Judgment and Salvation I spell out my position in greater detail. In short however, I’m a compatibilist.

“Compatibilism offers a solution to the free will problem. This philosophical problem concerns a disputed incompatibility between free will and determinism. Compatibilism is the thesis that free will is compatible with determinism. Because free will is typically taken to be a necessary condition of moral responsibility, compatibilism is sometimes expressed in terms of a compatibility between moral responsibility and determinism.” (http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/compatibilism/)

This theory takes into account: Agency, Determinism, Free-Will, Morality and Ethics. I apply this theory to Human Will and Sin. Which is what I will deal with presently.

My fear with Luther is, regardless of the biblical evidence marshalled against him he will either ignore it or wrongly interpret it to preserve his theology.

The Human Heart

What seems critical to me, but almost completely absent in Erasmus’ and Luther’s discussion on free-will is the human heart. I’ve done a word study on it here.

In my understanding of the scriptures, the human heart is the control centre of a person’s being. The centre of their will and desire (Ex 35.22; 1 Chr 28.9; 29.9; 2 Chr 29.31; Ps 37.4; 1 Cor 4.5; 7.37; Eph 6.6). The heart is the place where a person makes their decisions. In my opinion, Any real discussion on the man’s free will really should be about the human heart.

I acknowledge with Augustine and Luther, it’s a given in the scriptures there is a problem with the human heart. People are born in sin. I assume the general rule that at the start of everyone’s life every inclination of their hearts is evil (Gen 6.5-9; Jer 17.9-10).

But, in the scriptures God promises to do an amazing work in the hearts of his people. Be promises to circumcise their hearts, to give them a new heart and to write his laws upon their hearts (Dt 30.6; Jer 31.33; Eze 36.25-27). In the New Testament, followers of Jesus seem to be beneficiaries of these promises (Rom 2.28-29; 10.9-10).

But, in the scriptures God promises to do an amazing work in the hearts of his people. Be promises to circumcise their hearts, to give them a new heart and to write his laws upon their hearts (Dt 30.6; Jer 31.33; Eze 36.25-27). In the New Testament, followers of Jesus seem to be beneficiaries of these promises (Rom 2.28-29; 10.9-10).

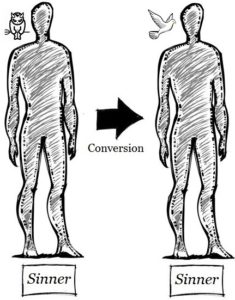

If God gives good gifts to us, it’s our responsibility to use them appropriately (1 Pet 4.10-11). God has circumcised believers hearts by the Spirit. Now their hearts are empowered to will and desire the good and it’s our responsibility to do so (Mt 12.34-35; Rom 6.17-19). Luther seems to deny this. For him believers do not change with respect to their will when they are initially saved.

Barclays (review) comments apply in a couple respects;

Luther seeks to preserve the incongruity of grace as its quintessential characteristic, applicable to every dimension of the believer’s life. It is this perfection of grace as a permanent incongruity that makes the Lutheran theology of grace stand out from its context, (p101, Barclay, Paul and the Gift)

[Luther] is wary of the presumption that anything of salvific value inheres in believers themselves. This sense of living not in oneself but in another (cf. Gal 2:19-20) gives to the Christian life an indelibly “eccentric” character, and stations believers permanently at the point of conversion. Whatever may be said about their “maturity” or “progress,” they are forever dependent on an undeserved grace. For these reasons, Luther has no desire to stress the efficacy of grace in the heart of the believer. (p111, ibid)

I found these reflected Luther’s statements in Bondage of the Will. Consequently I wonder if Luther is only offering lip service in saying he believes God’s promises. God promised He will work in the hearts of believers giving their hearts the ability to choose the good and therefore do good works.

Human Agency in Salvation

One of Luther’s main reasons for denying the existence of free-will with respect to salvation is because he feels if that were granted no one could have assurance of salvation.

I feel in this case Luther has made assurance a hermeneutical criterion for his interpretation of scripture.

This assertion sadly creates tensions with scripture which state believers are involved in their salvation (Phil 2.12-13) and a believers works are instrumental in their receiving rewards (Lk 14.12-14; 1 Cor 3.12-15) and eternal life (Mt 25.31-46; Gal 6.7-10).

See my page on Future Judgment and Salvation for more details.

Recommendation

In Council we have zones of land which are ‘heritage listed’. This does not necessarily mean they look good or are fit for purpose. What the designation means is that their character is representative of history and needs to be preserved and valued.

Luther’s Bondage of the Will is similar in that it is a classic piece of historical literature and displays prominent aspects of Luther’s and reformation theology. For this reason I recommend reading this great piece of history.

Luther’s theology of course needs to be weighed against scripture if we are to remain true to the reformation principles of sola scriptura, ad fontes and semper reformanda.

Luther has rightly recognised God’s Sovereignty in salvation and his focus on Christ is commendable. However his belligerent and arrogant attitude suggest something is wrong with his theology.

Luther does not associate the human will with the heart. He downplays God’s promises to change the heart and the work of the Spirit in doing so. I fear his zeal to maintain assurance by freeing believers of any involvement in their salvation has introduced many unnecessary tensions in scripture which I still see in reformed churches today.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2017. All Rights Reserved.