This book gives a broad outline of reformation history, theology and practice in comparison with medieval Roman Catholic theology. The polemical (Reformed vs. Catholic) content of this book comes off a bit haughty at times and reminds me of the Pharisee condemning the tax collector. ‘Look how great the reformers are, look how bad the Catholics are, you should go with reformed theology.’ Nonetheless, this book is a great summary of key elements in the Reformation and I recommend it for this reason.

This book gives a broad outline of reformation history, theology and practice in comparison with medieval Roman Catholic theology. The polemical (Reformed vs. Catholic) content of this book comes off a bit haughty at times and reminds me of the Pharisee condemning the tax collector. ‘Look how great the reformers are, look how bad the Catholics are, you should go with reformed theology.’ Nonetheless, this book is a great summary of key elements in the Reformation and I recommend it for this reason.

- Link: Amazon, ChristianAudio

- Length: 224

- Difficulty: Medium, Easy-Popular

- Topic: Theology, Topical

- Audience: Mainstream Christians

- Published: 2016

For the most part I think the reformers were right to correct the Roman Catholic church. At the time much moral reform was needed and the basic principles of scriptural authority (sola scriptura), back to the sources (ad fontes) and always reforming (semper reformanda) for me are foundation for scriptural interpretation.

I listened to the audio version which was offered free from ChristianAudio some time ago. It’s probable because of this is missed how the chapters were structured because various headings were only in the book.

This post is one of my book reviews.

Contents

Main Points

Each chapter in the book seems divided into three sections.

- History of the reformers

- Interpretation of Scripture

- Application for Protestants

This structure shows the authors of the book have extensive knowledge (historical and theological) of the reformation and are writing for the wider Christian audience.

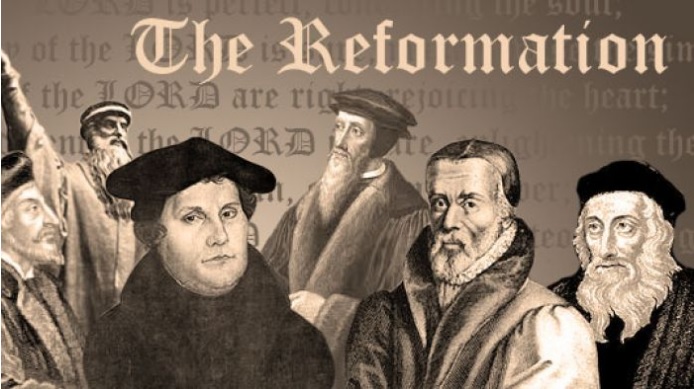

Introduction

The introduction gives a good overview of the main reformers, key dates and places. For example Luther at Wittenberg, his debate with Etzel, His famous, ‘Here I stand’ statement at the Diet of Worms, and Calvin and Farrell at Geneva. They then begin to discuss core tenants of reformation theology and gave some introductory reasons into why the reformation still matters today. They say the reformation still matters because ‘the debates have not gone away‘.

For me the presence of continuing debates is understandable. If a doctrine or interpretation introduces tensions, even contradictions in scripture and reason. Then its entirely logical people will continually question it. ‘Are you sure this is right?’ ‘This doesn’t make sense’. ‘Your interpretation doesn’t seem to fit this passage?’ ‘Why don’t we see this understanding reflected in early church history?’

The first few chapters discuss Justification, Sin and Grace. All these chapters give a broad understanding of how these topics are understood in reformational theology. I can’t really fault them for missing out anything substantial.

That being said I think it’s appropriate to make an observation for what I think seems to be how many reformed interpret scripture. Note from the contents, the book lists Justification before Scripture. In many cases the order of the contents can express their importance. Justification is listed before Scripture because I think this doctrine has more importance to them.

1 Justification – How can we be saved?

In addition to touching upon the imputed (status) vs imparted (healing) contrast with justification, the early discussion on Luther’s background is quite instructive in understanding his headspace. Luther was excessively prone to anxiety, introspection and was constantly in fear of unknown sins he had not confessed believing these jeopardized his salvation. (See Stendahl – Introspective Conscience of the West) Luther was an avid student of the scriptures and in particular his study of the expression the ‘righteousness of God’ in Romans 1.16-17 caused him to fear. But after struggling over the passage he realised he could interpret the expression differently than his contemporaries and this opened for him the ‘floodgates to paradise’. His lack of assurance was cured. He found this interpretation of justification fit other portions of scripture better than the current interpretation held by the Roman Catholic church. The Reformation was born. The authors apply this doctrine to today’s infatuation with busyness.

For Luther and many reformers, assurance seems to be a hermeneutical criterion for interpreting scripture. Any interpretation of justification, sin, grace, the righteousness of God, indeed any interpretation of scripture must (for them) maintain assurance of future salvation to be a valid. ‘We affirm what the scripture says, so long as it maintains our understanding of justification and assurance’. Any alternative interpretation that undermines their prior assumptions, in my experience, is ruled out from the onset.

2 Scripture – How does God speak to us?

The chapter begins highlighting a significant debate at Leipzig between Martin Luther and a Roman Catholic named Johann Eck about Huss. The Roman Catholic Church claims the scriptures and the authorised church’s interpretation of scripture (‘tradition’) carried authority. The reformers claimed scripture alone has authority. This is argued to be the ‘formal principle’ (foundation?) behind all reformed doctrines. The chapter goes on to explain the reformed understanding of the power of scripture, argue that preaching is the word of God and describe the marks of the church. The chapter covers the topic well.

Several Roman Catholic books I have read highlight that as a result of the scripture alone principle, the church has fractured and divided many times. The Roman Catholic Church for the most part remains unified because (right or wrong) it conforms to one interpretation. The Protestant church is quite divided.

I also think it concerning that for all the argument against papal authority, the protestants have only replaced the pope with themselves in asserting their interpretations are the only valid ones and claiming their preaching (interpretation) has the authority of the word of God. Isn’t this just a return to the Catholic position? When I hear Protestants condemning Catholics for relying too heavily on their tradition, I tend to think they have a bit of wood in their own eye as well. Many years since the reformation have progressed and our understanding of the scriptures has improved as well. Now when improvements to our understanding of the bible challenge reformed doctrine, its todays reformers who insist on their tradition.

As NT Wright once said of the Protestants condemning him;

To find people in avowedly Protestant colleges taking what is basically a Catholic position would be funny if it was not so serious. To find them then accusing me of crypto-Catholicism is worse. To find them using against me the rhetoric that the official church in the 1520s used against Luther — ‘How dare you say something different from what we’ve believed all these centuries’ — again suggests that they have not only no sense of irony, but no sense of history.

I want to reply, how dare you propose a different theological method from that of Luther and Calvin, a method of using human tradition to tell you what Scripture said? On this underlying question, I am standing firm with the great Reformers against those who, however Baptist their official theology, are in fact neo-Catholics. (Wright, N.T., 2013. Pauline Perspectives: Essays on Paul, 1978–2013, Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press.)

Protestants like to highlight many Catholic beliefs are unbiblical (e.g. praying for the dead), but if you remove whole sections like the apocrypha, which has been in the scriptural canon for over a thousand years, from the bible. Isn’t it a bit rude, after cutting out these out from the bible, to then claim teachings and beliefs derived from these sources are unbiblical? I’m not a Catholic, but I look at how protestants sometimes behave and argue and I’m not impressed.

3 Sin – What is wrong with us?

The chapter describes the medieval philosophical belief a person has to do righteous deeds in order to become righteous. This chapter captures the argument surrounding this false belief well. Many believed they ought to do righteous things, to tighten up their boot laces so to speak. Luther on the other hand believed the problem of sin runs deep in all people. Our hearts are corrupt and our wills do not desire to obey God. The chapter discusses his written debate with Erasmus (review here). Again, what seems to be presupposed in Luther’s arguments is his need for assurance. If people were able to repent of their sin and do the right thing (e.g. Eze 18.5f), then salvation in part would depend on our involvement. This I suspect is intolerable for Luther.

The description of Luther seems to alternate between lumping believers together with unbelievers regarding their hearts, minds and at other times highlighting God has promised to change people’s hearts (and therefore wills) by the Word and Spirit. A quote from his 97 theses is quite encouraging;

40. We do not become righteous by doing righteous deeds but, having been made righteous, we do righteous deeds. (95 theses)

However for the most part I assume Luther in practice did not operate under the assumption that at conversion believers hearts and minds undertook radical change. As Barclay writes of Luther;

[Luther] is wary of the presumption that anything of salvific value inheres in believers themselves. This sense of living not in oneself but in another (cf. Gal 2:19-20) gives to the Christian life an indelibly “eccentric” character, and stations believers permanently at the point of conversion. Whatever may be said about their “maturity” or “progress,” they are forever dependent on an undeserved grace. For these reasons, Luther has no desire to stress the efficacy of grace in the heart of the believer. (p111, Barclay, Paul and the Gift, review)

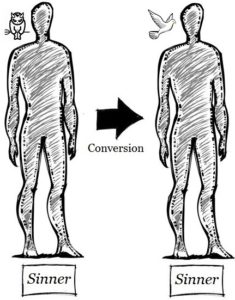

For Luther, believers remain sinners, but are now under the influence of the Spirit.

Luther has a miserable sinner understanding of Christianity. His famous expression, ‘Simul iustus et peccator’ highlights he does not believe anyone is righteous with respect to their character or behaviour. Rather it seems more like to him, everyone is a sinner and no one practices righteousness or keeps God’s commands. His problem is he only focuses on sin and refuses to look the general practice and behaviour of people, which is what the authors of scripture do. This is the pessimistic heart of Lutheranism that refuses to acknowledge scripture which says otherwise. It’s a core hermeneutic for determining the meaning of the scriptures and especially what Paul means by his justification expressions.

The upshot for this is that justification for him can never refer to the identification of the righteous. Because in his mind the righteous don’t exist. It means the righteous can never be identified by their practice of righteousness because according to him no one can keep the law, everyone keeps on sinning. It’s logical from this set of assumptions, justification could never make a person righteous (Augustine) or identify who is righteous. Rather is must be a declarative fiction which covers over the reality that everyone is a sinner and no one can be righteous in terms of their character or behaviour.

4 Grace What does God give us?

Early on the discussion on grace highlights medieval Roman Catholic theology also emphasised the need for grace in salvation. The difference however between Luther’s understanding of grace and the Catholic understanding again seems to hinge on assurance and whether or not people are involved in their salvation. The Catholics understand grace to be God’s enabling of the person by the Spirit to do God’s will and his acceptance of their works. For Luther, if believers have to do anything in order to be saved, this would undermine assurance. This option is ruled out from the onset.

Luther’s understanding of grace is depicted as a marriage between Christ and the believer (church?). Everything that is ours (our sin and weakness) goes to Christ, everything that his Christ’s (his very self and righteousness) becomes ours. The illustration is very much like double imputation. His understanding is quite relational, the Catholics understanding is represented as quite abstract and dull. Supposedly, Catholics understand grace to be a ‘thing’, a ‘force’ or some sort of ‘substance’. I strongly suspect no Catholic theologian would describe their understanding of God’s grace in such unattractive terms.

The book will then go on to address Dietrich Bonhoeffer and his concept of cheap grace. It defends the reformation view from the accusation of cheap grace by again affirming that God’s gracious gift is Christ himself. This seems to be a dodge, as I’m not sure how it overcomes Bonhoeffer’s argument which of course stresses people are involved in salvation. They have to repent, they have to obey, they have to pick up their cross, they have to follow Christ as his disciples.

As John Barclay has noted in his book Paul and the Gift (review), the reformed understanding that God’s grace does not have an efficacious and reciprocal character is mistaken. Its false teaching to deny it. What the reformers have captured rightly is the incongruous nature of God’s grace, it’s superabundance and priority.

5 The Theology of the Cross – How do we know what is true?

Luther came up with two opposing concepts: The theology of the Cross and the theology of Glory. For the most part the theology of the Cross embraces humility, weakness and suffering. While the supposed theology of Glory seeks pride in accomplishments, strength and pleasure.

Luther came up with two opposing concepts: The theology of the Cross and the theology of Glory. For the most part the theology of the Cross embraces humility, weakness and suffering. While the supposed theology of Glory seeks pride in accomplishments, strength and pleasure.

The chapter breaks down key features of Luther’s theology of the Cross. These revolve around revelation (how we know things about God). This revelation is hidden and found in the cross of Christ, not through human works or reason. It comes through the message of the Cross, through faith and particularly through suffering (humiliation). There is lots to like in this chapter.

6 Union with Christ – Who am I?

Some people say the centre of Paul’s thought is ‘union in Christ’. This little expression is used to encompass the following in Paul’s writings: In Christ, In the Lord, In Him, Into Christ, Into Him, With Christ, With the Lord, With Him and Through Christ.

The chapter begins by likening Union in Christ to a marriage. Christ is married to church. Viewed this way union in Christ is primarily a relational concept. The chapter then goes on to describe how union in Christ affects our identity. God’s people are known as Christians.

The chapter then moves on to address how union in Christ gives people a righteous standing before God. In a similar manner to the forces driving the theology behind imputation this aspect of union in Christ also has in mind righteousness, justification and final judgment. The authors child NT Wright’s criticism of imputation and call it ‘droll’. They say those who are in Christ are ‘clothed’ in his perfect obedience and righteousness and are therefore themselves righteous in God’s sight. This again is a source of assurance for protestants.

The chapter to a large degree leaves out incorporation into Christ’s death, burial and resurrection. I felt this was a major omission.

7 The Spirit – Can we truly know God?

The discussion on the Spirit discusses the Spirit’s role in revealing God and giving people new life. Like several chapters before they depict their opponents as having a Pelagian view of initial salvation (i.e. by a sinners – unbelievers efforts they can know God). They discuss the Spirit’s work in the hearts of people through the gospel, the definition of ‘faith’ and assurance.

The discussion on the Spirit discusses the Spirit’s role in revealing God and giving people new life. Like several chapters before they depict their opponents as having a Pelagian view of initial salvation (i.e. by a sinners – unbelievers efforts they can know God). They discuss the Spirit’s work in the hearts of people through the gospel, the definition of ‘faith’ and assurance.

They say that, ‘still today Christians display a strong gravitational pull away from knowing God’. In my mind they are claiming superiority and attempting to criticise many claiming to be Christian who fail their litmus test of authenticity.

For the most part I found this chapter to espouse an under-realised eschatology. Generally lumping believers and unbelievers together. They seem to communicate that believers in themselves remain unchanged and are still incapable of obedience. When they do obey it is the Spirit’s work, not them. Believers need a changed heart to obey. In saying this they seem to imply, believers will not have a changed heart this side of Christ’s return. Which is of course wrong.

They look down on any assumption a person could do something Christ would have without first acknowledging God’s (monergistic) role and seeking His help. I not sure I see how Jesus or the apostles recommended this when they gave imperatives for their audiences. Rather their instructions to me seem to imply they think their audiences could obey without having to acknowledge the Spirit’s involvement.

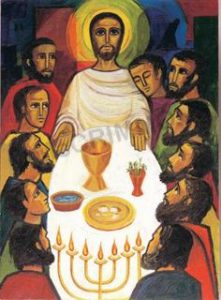

8 The Sacraments – Why do we take bread and wine?

The chapter begins discussing the Roman Catholic understanding of the Lord’s Supper. Their understanding of the sacraments is intrinsic to their view of sin and salvation (healing). Their view is also called ‘Transubstantiation’. The bread and wine really became the body and blood of Jesus. Regular participation in the Lord’s supper is seen as a meritorious act and a means by which God enabled participants to do God’s will.

The chapter begins discussing the Roman Catholic understanding of the Lord’s Supper. Their understanding of the sacraments is intrinsic to their view of sin and salvation (healing). Their view is also called ‘Transubstantiation’. The bread and wine really became the body and blood of Jesus. Regular participation in the Lord’s supper is seen as a meritorious act and a means by which God enabled participants to do God’s will.

Once again the Catholic view of grace is depicted as a ‘thing’. I wonder if a Catholic priest if asked would describe their understanding of grace as a ‘thing’ and not at all relational. This seems like a straw man depiction to me.

Interestingly in the Catholic mass only the laity were allowed to take the bread. Regular members could only take the wine. These aspects of the Lord’s supper are then compared with the Lutheran.

In the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, Luther rejected the Catholic explanation of it saying it can be accepted by faith and limiting its participation to the laity. The Lord’s Supper was an aid to belief, not a meritorious act.

Luther agreed with the Catholics that Jesus is (physically) present in the bread and wine. Interestingly Luther’s view is based on his belief that Jesus, being God, is onmipresent. Therefore he is physically present even in the bread and the wine of the Lord’s Supper.

Luther’s understanding of the Lord’s supper is compared with Zwingli is several ways.

9 The Church – Which congregation should I join?

The chapter begins discussing Luther’s predicament after he was excommunicated from the Roman Catholic church. This was a real issue in those times because religion was so enmeshed in national politics and society. Fortunately he had powerful supporters who could help him. He also comforted himself thinking that it wasn’t that he that was apostate from the church. Rather it was the Roman church who was not the true church because it had denied the ‘Gospel’.

The so called ‘Gospel’ in this chapter is synonymous with the reformed interpretation of ‘justification by faith apart from works of law’ (e.g. See Trevin Wax on Piper). Because the Roman Catholics rejected this understanding of justification and the gospel they were deemed by the protestants to be an apostate church.

Personally I think, so long as Roman Catholics still understand the gospel to be the narrative of the words and deeds of the saviour Jesus Christ they still fall under the umbrella of what is a true church. The protestant insistence of the gospel being justification by faith to me is more of an attempt to justify their own existence apart from the Roman Catholics.

This leads into a discussion on the marks of the church. The marks of the church are characteristics and behaviours of a gathering of people which identify it as the church. Sort of like NT Wright’s understanding that faith is the new covenant boundary marker for the Jew-Gentile people of God, not the Jewish only works of law. Protestants typically understand the marks of the church to be the right preaching of the gospel and administration of the sacraments.

The discussion then looks into the differences between the magisterial reformers and the radical reformers with baptism being the main focus. It gives a fairly balanced discussion for the rationale behind the rebaptism of the time and adult baptism.

10 Everyday life – What difference does God make on Monday mornings?

11 Joy and Glory – Does the reformation still matter?

The last two chapters really sum up much of what has been said before and give an argument why the reformation still matters.

Recommendation

As I mentioned in the introduction and hopefully I have shown from the body of this review, this book will detail an good amount of reformation history, theology and practice.

The overall content of the book is polemical in nature, as it has to be, because the reformation involved considerable debate with the Roman Catholics on important doctrines. Unfortunately the polemical nature of the discussion makes the authors come off bit haughty and superior as they denounce the Catholics and commend their own position.

I felt the attention to key events and writings of reformation history is excellent. People reading this book will touch upon multiple events and writings that mark the history.

While I have some issues with reformation theology and hermeneutic, as described above, the book does give a good example of normal theological arguments which attempt to support their doctrinal stands.

Unfortunately along the same lines, I find the reformation leans to heavily on the need for assurance in how they interpret scripture. Ultimately, this practice undermines the core principle of sola scriptura itself. Scripture is not allowed to speak differently. Several arguments seem to me to cherry pick one set of verses and ignore others in their favour. Which is part of the reason why I think the debates still continue.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2018. All Rights Reserved.