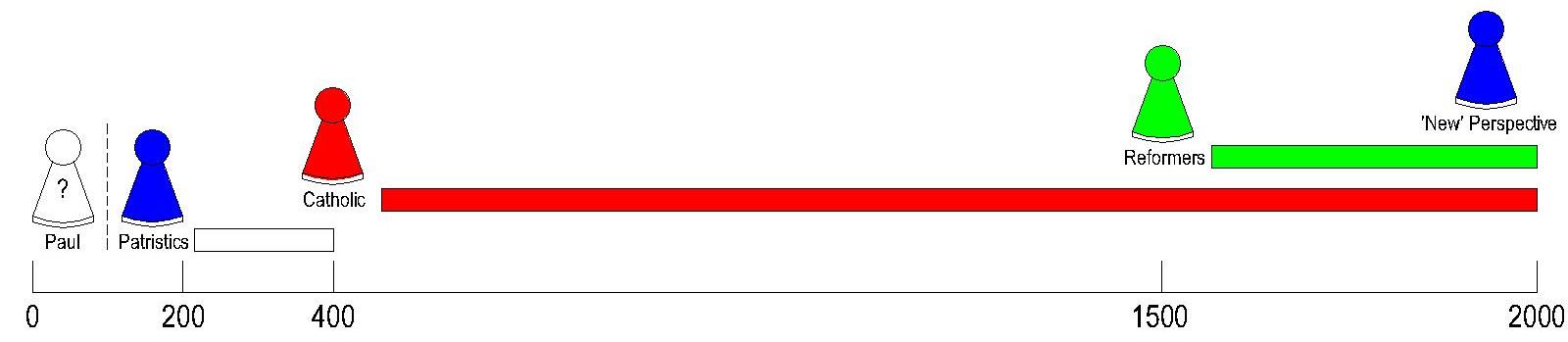

The interpretation of Paul’s expression ‘justification by faith apart from works of law’ has had a profound effect on church history. This is why books addressing the historical continuity of the expression’s interpretation are valuable contributions to the associated debates. Thomas’ book is a good example of the reformational principle ad fontes and argues the New Perspective provides superior historical interpretative continuity than that argued by the Reformers.

The interpretation of Paul’s expression ‘justification by faith apart from works of law’ has had a profound effect on church history. This is why books addressing the historical continuity of the expression’s interpretation are valuable contributions to the associated debates. Thomas’ book is a good example of the reformational principle ad fontes and argues the New Perspective provides superior historical interpretative continuity than that argued by the Reformers.

- Link: Amazon

- Length: 269 pages

- Difficulty: Heavy-Academic

- Topic: Historical, Theology

- Audience: Academic and Educated Christians

- Published: 2018

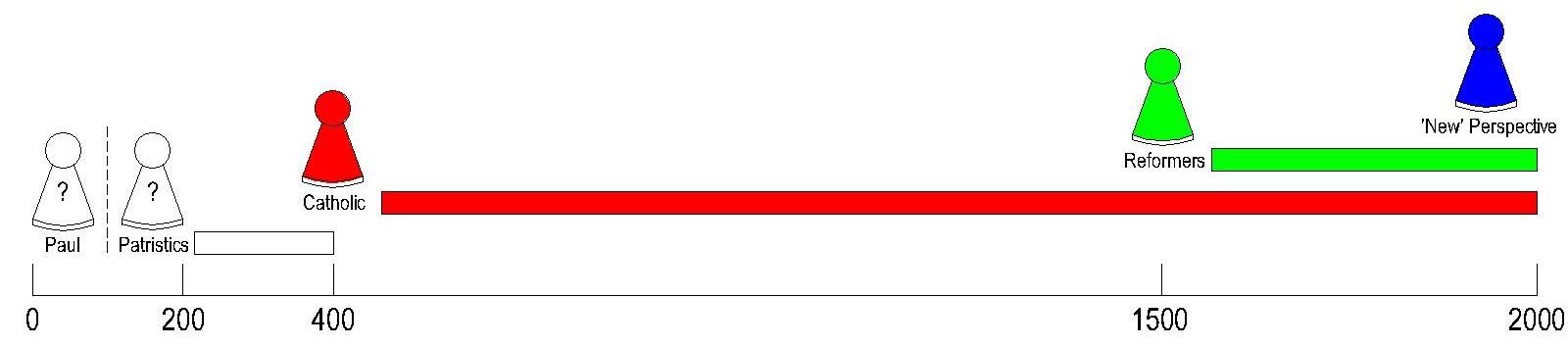

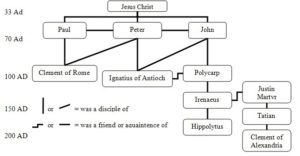

The book follows the presupposition that it’s logical to assume the early church (Paul, the other apostles, the early christians) orally passed on their theology and apologetics to the Christians around them. The concept is called ‘living memory’. Thomas intentionally engages with patristic authors who were alive when the apostles were in order to summarise how they understood the ‘works of law’.

Note that I have set reading difficulty to heavy-academic. The book itself is a slight modification of Thomas’ phd thesis. So it is pitched for people at that level. There are a few references to more recent works, however there are many obscure references to old commentaries on the patristics. He works from the original Koine Greek of these writings often, fortunately most of his quotes are in English. He occasionally quotes German and French scholars in their native languages (I had to use google translate). Personally I’ve done a bit of reading in Paul, Justification and the Early Church, so I was able to comprehend it well, but those not well read in these topics may struggle. Consequently, while the book itself has an academic target audience, my review will attempt to tone it down for a more general audience (see also reviews by Scot McKnight and Mike Bird).

This post is one of my book reviews. It’s a relatively long review, however I believe many will find it interesting.

Contents

Introductory Comments

This book, while one third the size, bears some similarities with Sanders’, Paul and Palestinian Judaism (review). It is similar in that it is interacting with primary sources in order to develop some sort of historical understanding. In Sanders case, he sought to identify a pattern of religion common to the Palestinian Judaism of the Second Temple Period. He did this by examining a fair amount of Second Temple literature (Palestinian Judaism). Thomas looks at the patristic writings during the period of overlap between the apostles and the early church. He wants to gather insight into how they regarded the ‘works of law’.

This book, while one third the size, bears some similarities with Sanders’, Paul and Palestinian Judaism (review). It is similar in that it is interacting with primary sources in order to develop some sort of historical understanding. In Sanders case, he sought to identify a pattern of religion common to the Palestinian Judaism of the Second Temple Period. He did this by examining a fair amount of Second Temple literature (Palestinian Judaism). Thomas looks at the patristic writings during the period of overlap between the apostles and the early church. He wants to gather insight into how they regarded the ‘works of law’.

With this in mind, readers of this book and review ought also to be mindful of the book’s scope. Thomas has not done a full range study on significant topics associated with works of law. The book is reasonably focused on identifying the works in question, their significance and why they were rejected by the patristics. It isn’t intended to go beyond this, at least in great detail.

Regarding justification and salvation for example Thomas writes;

“Though itself the subject for another study, the common soteriological pattern of the early patristic sources is that initial justification is completely by grace apart from works of any sort, and that final judgment (or final justification) is based on the outworking of this grace in one’s subsequent life. Within this paradigm, the works of the Mosaic law have no role, either as bearers of the grace of salvation (or somehow prerequisites for it), or as criteria that will have any kind of significance at the last judgment. While the second century sources would affirm with Luther that no works are necessary for initial justification, they would still regard works as the basis for final justification.” (221)

In the footnote he refers to another scholar who has already done this. (See also this essay from Chris Erickson on Salvation from the Perspective of the Early Church Fathers, and my own reading of Future Judgment and Salvation in the NT).

Likewise a full exegesis of the Romans and Galatians texts surrounding the ‘works of law’ passages is beyond the scope of the book;

With respect to limitations of scope, this study focuses its analysis on the early patristic sources and their relation to the old and new perspectives, and does not engage in detailed analysis in related areas (such as exegetical analysis of Romans and Galatians, possible reception of these debates in NT texts, correspondence in Second Temple Jewish sources, and wider history of reception). (18, cf. p227)

(Note: I’ve given this a go in my Simply Galatians series)

Some well known sources are noted to be omitted upfront because they do not match the search criteria. Notably 1 Clement to the Corinthians;

With regards to the sources engaged, this study seeks to avoid admitting false positives into its analysis by only engaging contexts which, like Paul’s discussions in Romans and Galatians, show evidence of conflict with Jewish parties regarding the law and/or works. This means that texts such as 1 Clement and Polycarp’s Philippians are not evaluated, which, though containing general material on justification / salvation and works, show no evidence of conflict with Jews or dispute over the law. (18-19, cf. p221)

(Note: I’ve given the 1 Clement to the Corinthians a look in here.)

Given all this, its apparent Thomas has covered some significant bases in approaching this topic and I believe the findings of this book are a valid contribution to these others. (My series on justification in the early church has already done some research into this btw).

Part I: Introduction

Chapter 1: Introduction, Theory and Methodology

Effective History and Living Memory

In this section, Thomas introduces the concept of ‘living memory’. He quotes Bockmuehl who says;

“New Testament studies on this view could find a focus in the study of the New Testament as not just a historical but also a historic document. Its place in history clearly comprises not just an original setting but a history of lived responses to the historical and eternal realities to which it testifies. The meaning of a text is in practice deeply intertwined with its own tradition of hearing and heeding, interpretation and performance. Only the totality of that tradition can begin to give a view of the New Testament’s real historical footprint, the vast majority of which is to be found in reading communities that, for all their diversity, place themselves deliberately “within the living tradition of the church, whose first concern is fidelity to the revelation attested by the Bible.” And conversely, that footprint, for good and for ill, can in turn serve as a valuable guide to the scope of the text’s meaning and truth.” (Markus Bockmuehl, Seeing the Word: Refocusing New Testament Study, ed. Craig G. Bartholomew, Joel B. Green, and Christopher R. Seitz, Studies in Theological Interpretation (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2006), 65.)

I thought the book and concept so interesting and right up my alley in interpreting the NT, so I purchased the book. On my to read list.

The concept of ‘living memory’ builds on Bockmuehl’s point arguing “the early witnesses that follow within a period of ‘living memory’” who, “retain a personal link to the persons and events concerned” provide “a uniquely privileged window” into the interpretation of the New Testament authors. This window extends ‘up to 150 years … when there were still living witnesses of the apostles or of their immediate students” (6).

The concept of ‘living memory’ builds on Bockmuehl’s point arguing “the early witnesses that follow within a period of ‘living memory’” who, “retain a personal link to the persons and events concerned” provide “a uniquely privileged window” into the interpretation of the New Testament authors. This window extends ‘up to 150 years … when there were still living witnesses of the apostles or of their immediate students” (6).

The guts of this argument is to state something blatantly obvious to me – our interpretation of Paul’s intended meaning regarding justification by faith apart from works of law (Gal 2.16; Rom 3.28), really ought to give a fair amount of weight to these early witnesses’ and their understanding of the same. Who would you bet on to have a more accurate understanding in a game of chinese whispers – the first person following the lead or someone way down the line? However, I wonder if some write off the argument because they won’t like where this will lead them (‘Cavalier dismissal’, p118, Carson, Exegetical Fallacies).

Now before we jump to the conclusion that Thomas assumes the Patristics understood Paul perfectly. Please note his use of Bockmuehl again to utilise the concept of smoke and fire to explain he is not trying to argue for a definitive interpretation of Paul. Rather the early patristics understanding of the Mosaic works and Paul point to or can give us invaluable leads to better understand them.

“The function of this early testimony can be illustrated by borrowing and adapting an analogy from Bockmuehl regarding smoke and fire. This book attempts to identify how the “smoke” of early effective-history might help us adjudicate between competing accounts of the “fire” – the conflicts over works of the law – that Paul and his congregations were engaged in.

While this smoke of second century testimony might be so widely dispersed as to only create a fog, if at all concentrated, it will constitute valuable evidence in evaluating whether the fire of these conflicts is located in one of the areas identified by the old and new perspectives – or it may perhaps lead us places that neither perspective currently identifies.” (7)

Methodology: Part 1 – Search and Identify

Thomas soon afterward discusses his criteria for selecting patristic sources and eliminating others in his study. He had a large number of sources to read through, and I assume behind the scenes he had to read many and evaluate them. For example check this link of early church writings. He stops with Irenaeus of Lyons. If we use this list as a rough guide he could have had up to 150 sources to sort through (some long, some short), and judging by the sources he reviews here he cuts this down to 14 primary sources. So how did he do this?

For him the primary indicators he looked for in the large body of writings were usage of Pauline verses discussing works of the law (Rom 3.20,28; Gal 2.16; 3.2,5,10) and similar discussions to Paul’s own as in Romans and Galatians. What exactly is a ‘similar discussion’?

- Conflict with Jewish Parties (e.g. Gal 2.15; Rom 2.17)

- Regarding the Law and works (e.g. Gal 2.3,16; Rom 3.19-20; 27-31)

As Secondary indicators he looked for discussion of themes common in the context of Paul’s arguments;

- justification,

- contrast with faith,

- relation of Jews and Gentiles,

- figure of Abraham,

- reception of the Spirit (ibid)

Thomas used these criteria to narrow the range of writings he engaged with.

Methodology: Part 2 – Categorization

Then once having selected a source for further study, he categorised it into one of three categories of how relevant the discussion was to his query;

- Category A – Direct evidence (use of Romans, Galatians, + citation of works of law verse),

- Category B – Supporting evidence (use of Romans, Galatians, , – works of law citation),

- Category C – Circumstantial evidence (minimal/unclear Pauline influence, similar conflicts with Judaism)

The book can be read without reading the patristic writings alongside. However, in order to adequately check whether Thomas’ readings and categorisation are fair, one needs to do so. For the most part I did this. In many cases it’s obvious (and necessary) that Thomas engages with the original Greek which is to be expected of the academic level he is engaging with. It’s a phd thesis.

Methodology: Part 3 – Three Questions

The most important part of his process is to ask three questions of what he reads. These three questions are;

- Meaning: What works of what law?

- Significance: What does the practice of these works signify?

- Opposition: Why are these works not necessary for the Christian?

After doing this for each of his sources he can begin to collate his results and make some observations. Considering the importance of his methodology, I thought the amount of discussion he gave it relatively brief, but it seems well thought out and justified.

In the next section he dives into some contemporary scholarship to identify how they are reading Paul’s use of ‘works of law’ before engaging with the patristics for comparison.

Part II: The Old and New Perspectives on Works of the Law

I’ll be brief on these sections.

Chapter 2: The Old Perspective on Works of the Law

To represent the Old Perspective, Thomas looks at Martin Luther, John Calvin, Rudolph Bultmann (1884-1976) and Douglas Moo (1950-). In reading the works of these scholars he asks the above three questions relating to Meaning, Significance and Opposition.

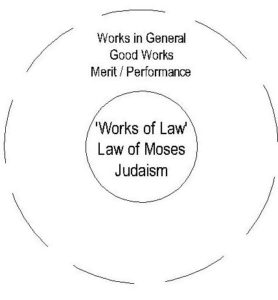

Meaning: For these scholars, while they acknowledge the law of Moses appears to be Paul’s immediate referent, they reject the idea Paul is focussing exclusively on the Mosaic law or any particular works it prescribes. Rather, they regard Paul’s target as human effort, performance or good works in general. The ‘works of law’ represent a subset of the broader category of good works, and the law in question being God’s requirements more generally.

Significance: All four of these figures see the practice of these works as an individual’s attempt to gain merit or right standing by their own achievements and earn salvation. (38)

Significance: All four of these figures see the practice of these works as an individual’s attempt to gain merit or right standing by their own achievements and earn salvation. (38)

Opposition: All four again reject the practice of works for justification / salvation, because in my own understanding of reformed doctrine; Sinless perfection is needed to stand righteous before God, and miserable sinners cannot keep the law perfectly. Luther and Bultmann go further and argue even the attempt to achieve righteousness by one’s own effort is sinful.

In his commentary, Moo highlights why this understanding is so important to those of the reformed persuasion;

“It is just at this point that the significance of the meaning we have given “works of the law” emerges so clearly. Any restricted definition of “works of the law” can have the effect of opening the door to the possibility of justification by works—“good” deeds that are done in the right spirit, with God’s enabling grace, or something of the sort.” (p209, Moo, NICNT Romans)

Basically for them, to fold on this definition of ‘works of law’ is to give future judgment according to works a foothold. Moo might have some give in other areas, but he recognises their backs are to the wall on this one. This would undermine Luther’s hermeneutical criterion of assurance of salvation.

Chapter 3: The New Perspective on Works of the Law

The meaning of the expression is now widely debated in contemporary Pauline scholarship. Turning to the New Perspective representatives, Thomas looks at E.P. Sanders (1937-), James Dunn (1939-), N.T. Wright (1948-) and Josh Washington (only kidding).

Meaning: These scholars generally see Paul’s emphasis by ‘works of the law’ as on the law of Moses. Within this law, they see Paul’s most prominent targets as circumcision, laws regarding food, and the observance of Sabbath. I agree with this.

All three agree that Paul does not mean to target “good works” in general, and that moral works belong in a different subcategory of Paul’s thought than works of the law. (See also p224-229, DeSilva, NICNT Galatians, p119-121, McKnight, NIVAC Galatians)

Significance: These works are rather adopted as group identity markers that signify one’s membership in God’s chosen people, the Jews.

Opposition: Within the New Perspective, Thomas found a bit of variance. Sanders argues Paul rejects the works of law because of his vocation to be an apostle to the Gentiles and their reception of the Holy Spirit. Dunn’s emphasis appeared more social, with Paul rejecting the works due to their role in separating and excluding believers as well as some salvation-historical reasoning.

Wright’s emphasis in particular can be regarded as covenantal, with Paul rejecting these works because of the universal scope of the covenant promises, the inability of Torah to repair the problem of humanity’s sinfulness brought about by Adam, and the new age inaugurated by Jesus’ fulfillment of the covenant. (60)

(At the end of the review I’ve written some technical notes regarding works of law.)

Moving on, Perhaps it’s a bit of a chicken before the egg kind of problem, however I would have thought that the respective understandings of ‘works of law’ and the associated concepts – in particular ‘justification’, once highlighted would have better validated the search criteria mentioned earlier to use in selecting patristic writings to analyse.

To be fair and as objective as one can be, the OPP understanding of ‘works of law’ and ‘justification’ would require Thomas’ search criterion to be broadened to include themes relevant to the OPP. Consequently with respect to being fair to OPP proponents I think the search criteria and results of his study would have benefitted by also seeking out themes such as;

- Future judgment and its basis,

- Sin and human inability,

- Merit.

The different understandings are a reflection of different framings of the same Romans and Galatians passages (e.g. Preaching Romans: Four Perspectives, Ed McKnight, Modica). Unfortunately, the texts are composed of a complex interaction of many themes and concepts and so judging between the two is not so clear cut. Efforts to understand the expression and its place within the overall argument have tended to emphasise different elements of the text. Sometimes the interpretation of the expression reflects an either/or choice, however some interpreters try and integrate both understandings (both/and).

Part III: Early Perspectives on Works of the Law

Part 3 of the book looks at each patristic source identified by the criteria as relevant.

While engaging in these sources, it becomes apparent Thomas’ operating definition of ‘works of law’ is any of the works, deeds or commands which are in conflict between Jewish and Christian parties, which end up all focusing on the law of Moses. The sources he reviews tend to break them down into subgroups. For example, Diognetus refers to animal sacrifices, food regulations, Sabbath observance, circumcision, and the new moons and fasts of the Jewish calendar. Thomas will refer to these as ‘works of law’, which is perfectly fine because that is what they are. Deeds which the Jews ought to do as commanded by God in the law of Moses. At the end of his study this gives him the ability to summarise the most common ‘works of law’ which were at points of conflict. (Note: The early usage highlights the law of Moses, while perceived at times as a unity, could be broken down into subgroups and understood that way).

Here are the sources Thomas engages with, the letter at the end represents the category of evidence he has grouped it under. I’ve added hyperlinks to many of the sources for readers to look at if they are interested.

- Chapter 4: The Didache (C)

- Chapter 5: The Epistle of Barnabas (C)

- Chapter 6: Ignatius of Antioch (B)

- Excursus I: Second Century Fragments (Preaching of Peter, Dialogue of Jason and Papiscus, Acts of Paul)

- Chapter 7: The Epistle to Diognetus (B)

- Chapter 8: The Apology of Aristides (C)

- Excursus II: The Ebionites, Marcion, and Ptolemy

- Chapter 9: Justin Martyr: Dialogue with Trypho (A)

- Chapter 10: Melito of Sardis: Peri Pascha (B)

- Chapter 11: Irenaeus of Lyon: Against Heresies (A)

For the next few chapters I will give two examples of what the patristics have written.

From the Epistle of Barnabas (classed as Category C), we read;

But let us inquire whether our people or the former is the heir, and whether the covenant is intended for us or for them. (13.1) …

6 You see by what means He has ordained that our people shall be first and the heir of the covenant. [Rom 4.9-11] 7 Consequently, if, in addition to this, our people is also pointed out in the story of Abraham, then we have reached the perfection of our knowledge. What, then, does He say to Abraham when he, the only believer, was accounted justified? [Gen 15.6; cf. Rom 4.3] Behold, Abraham, I have appointed you the father of the nations which, though not circumcised, believe in God [Rom 4.9-11]. (13.6-7)

Personally I find this quote very interesting in that it directly connects the counting of righteousness and justification with covenant membership. We ought to remember with Paul Himes that;

“Language is a social construct. Consequently, anybody who wishes to communicate must make sure that how they use a word has at least some overlap with how their audience is using it. Context is not enough to facilitate clear communication, if in fact a word is not being used in accordance with how others use it. … Serious study should not overly rely on lexicons at the expense of the literature of Koine Greek. As John A. L. Lee has convincingly demonstrated, too often lexicons do not conduct original research but merely repackage the work of those that have gone before. Obviously lexicons are helpful tools; my point is that they are not infallible. One cannot understand the semantic range of a particular word in the Bible without looking at its use in various other contexts.” (Paul Himes, Logos Academic Blog, https://academic.logos.com/the-meaning-of-words-part-1-words-and-concepts/)

For me then, if we look at how people in living memory of Paul are using the ‘righteousness’ word group, it’s possible for them to understand it can have covenantal implications.

In his discussion of Justin Martyr, Thomas weights into the debate over whether Dialogue with Trypho the Jew has any Pauline influence. Consider the following passage;

For they are all gone aside,’ ‘they are all become useless.

There is none that understands, there is not so much as one.

With their tongues they have practised deceit, their throat is an open grave,

the venom of asps is under their lips,

Ruin and misery are in their paths,

and the way of peace they have not known.’

Do you recognise this from one of Paul’s letters?

On one side of the debate, Paul Foster (Paul and the Second Century; Ed. M Bird, J Dodson, Ch 6) for example, argues it is unlikely Justin is influenced by Paul, or I guess that this is a Pauline quote. He argues one has to cite the author’s name in order to demonstrate influence. For my own part, I believe the following is a paraphrase of Paul’s OT references in Rom 3.11-17.

I suspect Justin does not appeal to Paul because he knows Trypho does not consider Paul authoritative. But Justin does assume Trypho accepts the Old Testament scriptures as authoritative. It follows from this, where Justin is using Pauline arguments from the Old Testament, he will refer to the Old Testament as the authority, not Paul. I believe Thomas is right to categorise Dialogue with an ‘A’ for Direct Evidence. This is a critical argument and he handled it well.

Justin will go on to satisfy Thomas’ search criteria saying;

“God demanded by other leaders, and by the giving of the law after the lapse of so many generations, that those who lived between the times of Abraham and of Moses be justified by circumcision, and

that those who lived after Moses be justified by circumcision and the other ordinances – to wit, the Sabbath, and sacrifices, and libations, and offerings;… (For you are not distinguished in any other way than by the fleshly circumcision, as I remarked previously.

For Abraham was declared by God to be righteous, not on account of circumcision, but on account of faith. For before he was circumcised the following statement was made regarding him:

‘Abraham believed God, and it was accounted unto him for righteousness.’ [Gen 15.6]

And we, therefore, in the uncircumcision of our flesh, believing God through Christ, and having that circumcision which is of advantage to us who have acquired it – namely, that of the heart – we hope to appear righteous before and well-pleasing to God:” (Dialogue, Ch 92)

Thomas picks up in several patristics how they understood the works of law referred to as ‘distinguishing’ features, rightly characterising them as ‘boundary markers’. (Cf. Diognetus, Epistle to Diognetus, Ch 3-4; 5.1; ‘justified by circumcision … and the other ordinances’, ‘distinguished by circumcision’, ‘appear righteous’, Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, Ch 92; I’d also add ‘justified by our works’, Clement of Rome, Clement to the Corinthians, 30.4-5)

Bear in mind, these themes are repeated to varying degrees through the patristics sources Thomas interacts with.

Part IV: Conclusions

Chapter 12: Conclusions

Before I discuss Thomas’ findings, I should note a couple things.

One. There is a possible elephant in the room. As Thomas notes early on in his methodology (11), only one of his sources explicitly uses the expression in question ‘works of the law’ (Ireneaus, Against Heresies 4.21.1). Note his operating definition of ‘works of law’ when engaging the sources above. As far as I know the closest references to the expression (who are not Paul) are:

- 4QMMT,

- Irenaeus (c.e. 125-202) (Against Heresies 4.21.1),

- Tertullian (c.e. 155-240) (PaulOpposesPeter),

- possibly Origen (c.e. 185-254) (WorksPaulRepudiates), though I feel this view is weakened by his understanding in Rom 3.20 (here) – Origen is a bit confused in Rom 3 IMO,

- Ambrosiaster (c.e. 366-384) (WorksofLaw),

- Pelagius (c.e. 360-418) (WorksofLaw) and

- Augustine (c.e. 354-430) (WorksofLaw).

Obviously many of these are beyond the stated scope of the book.

Two. There isn’t much discussion regarding the use of the term ‘ceremonies’ in the early church, which is later on identified as works of law (218). Critics of the NPP often characterise the NPP understanding of ‘works of law’ using this expression. It’s interesting to note the early patristics used this nomenclature as early as Tertullian (c.e. 155-240). Personally I would have been quite interested in tracking the use of this stand in expression for ‘works of law’.

Augustine also uses the term ‘sacraments’ at points. Likewise I think in some cases Luke’s use of ‘customs’ also represented Paul’s works of law (e.g. Acts 6.14; 21.21; 26.3; 28.17). The variance in terminology, I believe referring to the same concept, is interesting. 4QMMT and Paul’s use lead me to think the expression ἔργων νόμου was an in-house expression used by Jewish groups. Where as other people groups, while understanding what the Jews mean by ‘works of law’, would to refer to them in other ways.

Thomas’ conclusion is a fair summary of his findings. He is just reiterating in brief what he has just found. The section is initially divided up into the categories of evidence: Direct, Supporting and Circumstantial. Then he draws together the most important part of the book, his summarising conclusions.

I’ll group these by answering the following questions.

Is the Early Church understanding of the works of law variegated?

This is an important question really asking if the results are too varied to be useful.

“While the testimony of the extant sources is not identical – not every source mentions all of the same works, nor are the same reasons given for rejecting them in each case – there still exists a striking degree of cohesion among these early witnesses, both with regards to the works and law in question and the significance of practicing these works.

Though there is a wide range of argumentation regarding why these works are unnecessary for the Christian, these arguments frequently recur between the various patristic sources, and are broadly compatible with one another.

Further, there does not appear to be significant variation in the interpretation of works of the law between sources that show stronger influence from Paul’s discussions on the topic and those that show less, which suggests that the works and law under discussion in such debates were commonly known in early Christianity.” (215-6)

Thomas is not going out of his way to force one overarching scheme on his findings. In my opinion he is not being too doctrinaire or reductionistic. Rather his summary in my opinion is a simple reiteration of his individual findings. That is to say, his summary is supported by his sources.

What are the works of the law commonly referenced?

After reading all these patristics, Thomas observes the most common referenced;

“The principal works of this law that come into focus are circumcision, Sabbath and other Jewish calendar observances (such as new moons, feasts and fasts), sacrifices, and laws regarding food, with a focus on the temple and Jerusalem occasionally noted as well. The practices of the Mosaic law are consistently distinguished from good works more broadly” (216)

So the chief works of law, commonly references in the early patristics where there are conflicts with Jewish parties similar to that in Romans and Galatians are circumcision, Sabbath, Jewish Calendar observances, food laws and temple sacrifices.

Importantly Thomas highlights the early patristics commonly distinguished these works from the category of good works, which in many cases were encouraged and seen positively.

What is the significance of these works of law?

“The practice of these works signifies identification with the Jewish people, the Jewish covenant, and “Judaism,” the manner of life and worship prescribed in the Mosaic law. The Jewish nation, covenant and praxis are so closely linked that each can stand as a synecdoche for the others; to be a part of this nation means to be a member of their covenant, and to live and worship according to its dictates. The practice of these works also represents a corresponding move of separation from the Gentile nations.” (216)

shortly after he writes;

“These works are practiced because salvation is believed to be tied in with the election of the Jewish people, which one enters by observing the Jewish law. From a Christian salvation-historical perspective, it can also be said that practicing these works identifies one with the period before Christ’s advent, and with the juvenile and hard-hearted condition of humanity before its renewal by Christ.” (216)

The above quote is quite interesting in that it reiterates one of Sanders’ point in Paul and Palestinian Judaism in that ‘salvation is by membership in the covenant and atonement’ (p147, Sanders, Paul and Palestinian Judaism).

Why did the early Patristics reject these works?

Thomas recognises his sources answers to these questions don’t easily group together into neat categories. But as a rough summary he comes up with five main reasons;

- The arrival of the new law and covenant in Christ, the Messiah, whose teachings and ordinances replace those of the Mosaic law;

- The witness of the Hebrew Scriptures, in which the prophets testify regarding the Messiah and this new covenant, and the cessation of these previous works;

- The universal nature of this new covenant, which is promised to be for all nations, and which has its arrival confirmed by the Gentiles receiving grace and turning to God apart from becoming Jews;

- The transformation in humanity wrought by Christ, understood as the new birth or the circumcision of the heart, which renders the laws given to hard-hearted Israel unnecessary, and which allows the types and mysteries of Scripture to be rightly understood;

- The examples of Abraham and the righteous patriarchs, who were similarly accepted by God apart from these practices, and whose righteousness confirms that the Mosaic law and circumcision were not given for humanity’s justification. (217)

In my opinion, reasons (or categories) 1, 2 and 5 are primary. They all fit into the salvation-historical model I found when I did my readings. What is missing in this description, which might integrate 1, 2 and 5 better together was the early church’s understanding of the Gospel (see my series here, See also Campbell, Gospel in Christian Traditions, review).

The Gospel was understood as an epoch in salvation history, inaugurated by the coming of the Christ.

In the Gospel, Jesus (the Lawgiver) gave commands which he instructed his disciples to teach (Mt 28.19-20). In this understanding both the Law and the Gospel are historical narratives. Both contain commands and rules to obey (it was normal for Jews and Christians to glean moral principles from narratives).

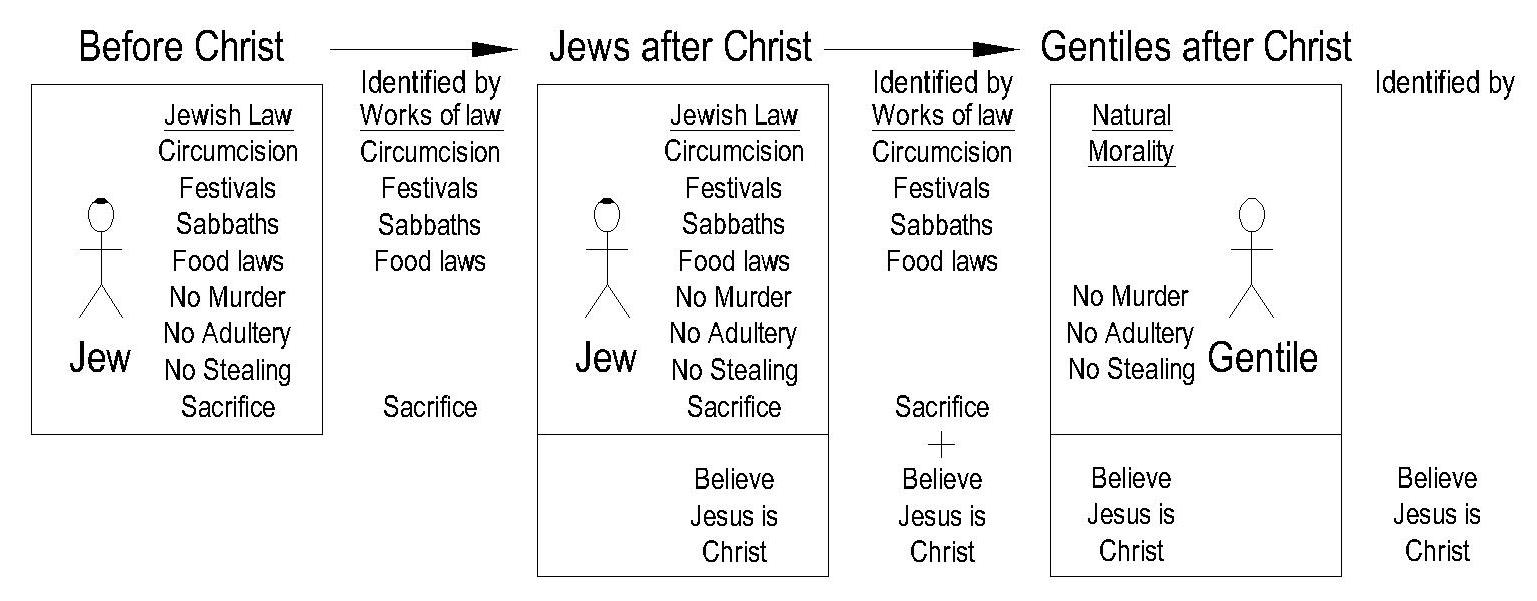

Thomas, referring to the patristic writers (esp. Justin Martyr), will afterward reason the small subset of commands commonly referenced above kept on cropping up in the patristics because of the overlap in practice between Judaism and the commands Jesus gave in the Gospel. Early on regarding most of their praxis, Jewish Christians had little difference from unbelieving Jews (other that believing Jesus was the risen Christ!). But when Gentile Christianity increased, the differences in praxis became more significant and thus the conflict.

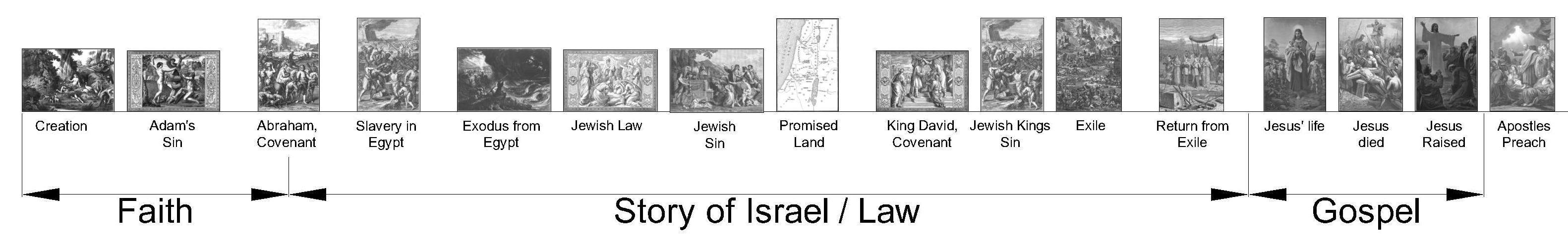

For Christians of course the whole law of Moses was abrogated with the coming of the Christ. They obeyed similar commands (e.g. to love and not to commit adultery) because Jesus commanded them, not because they were part of the law of Moses. Their conflict with the Jews was about what stood out as different, not the overlap they shared in common. I’ve attempted to explain this before using this diagram;

Importantly, the Gospel abrogates the period of the Law (Judaism, law of Moses, works of law and Flesh) and ushers in the new era of the Christ and the Spirit (Christ, Worldwide Christianity, Gospel, Spirit, Love).

Comparing Perspectives

So after all this Thomas compares the Old and New Perspectives with the ‘Early’ Perspective. I think it helpful at this point to bring out Westerholm’s contrast;

The formula has of late often been taken as an opening statement of his opposition: “A person (i.e., Gentile) is not justified (i.e., declared to be a member of God’s people) by works of the law (i.e., being circumcised, keeping food laws and the like) …” “To be justified” is thus construed as meaning “declared to be a member of God’s people,” “declared to be within the covenant,” perhaps even “declared to be a member of God’s family.” (p13, Westerholm, S., Justification Reconsidered: Rethinking a Pauline Theme, Review)

Vs.

We [Reformed] would expect Paul’s justification formula to mean something like this: “A person (i.e., Jew or Gentile, but necessarily a sinner in either case) will not be found righteous (and thus delivered from the divine condemnation that awaits sinners) by works of the law (i.e., by complying with the law’s demands—since that is not what sinners do), but through faith in Jesus Christ.” (p14, ibid)

Which do you think more closely resembles the patristics in living memory of Paul?

Thomas finds in favour with the New Perspective, particularly NT Wright;

“In summary, the early perspectives on works of the law are found to align far more closely with the so-called “new” perspective than the “old” perspective, particularly with respect to the meaning and significance of these works. On these issues, the alignment between early and new perspectives is such that one can regard the “new” perspective as, in reality, the old perspective, while what we identify as the “old” perspective represents a genuine theological novum in relation to the early Christian tradition.” (226)

Thomas’ description of the Old Perspective as a ‘genuine theological novum in relation to the early Christian tradition’ is actually a massive challenge to those who hold to the typical reformed understanding of ‘justification by faith apart from works of law’. As McGrath observes;

“If it can be shown that the central teaching of the Lutheran Reformation, the fulcrum about which the early Reformation turned, the articulus stantis et cadentis ecclesiae [article on which the church stands],

constituted a theological novelty, unknown within the previous fifteen centuries of catholic thought, the Reformers’ claim to catholicity would be seriously prejudiced, if not totally discredited.” (p211, McGrath, Iustitia Dei: A History of the Christian Doctrine of Justification)

This of course doesn’t mean that the New Perspective has the closest correspondence in every case. Thomas highlights that Sanders and Dunn were off the mark regarding why the works of law were opposed. Of the three NP scholars, Wright seems to be the closest. Regarding Wright, Thomas notes his undiplomatic language (which no doubt continues to perpetuate resentment), but suggests that if “Old Perspective” readers are satisfied by Wright’s emphasis on Torah’s inability to address human sinfulness (e.g. Rom 8.3), then they may find the early perspectives’ similar reasoning persuasive.

In light of these findings, I think it fair to say the New Perspective view of ‘justification by faith apart from works of law’ has a much greater claim to historical Christianity than the traditional reformed interpretation. Sanders has given us better insight into Second Temple Judaism preceding Paul and Thomas has now given us better insight into the early Patristics following Paul. The primary sources of these periods make the case that the New Perspective, in particular NT Wright, is closer to the mark in understanding Paul.

Recommendation

I obviously quite enjoyed reading the book and took the content seriously. For my own part I’ve been researching this for several years prior to the publication of this book. I feel however that Thomas has done what I could not do. To his credit he has engaged with the topic at an academic level and published the book which is now in academic circulation. He has put the argument on a platform where it can now be seriously engaged with.

The book itself, as I have mentioned before has an academic target audience. Because of this I would refer general readership to this review or another at the same level. Likewise the book requires some knowledge of the heresies of the day. (E.g. Marcion – think of an ancient version of Andy Stanley, who might never live down his statement to ‘unhitch the OT’) and ability to translate German and French theologians. This is not uncommon in academic works (e.g. Hays, Faithfulness of Christ). This can be overcome by available online translators. However it’s telling of the books target audience.

As mentioned earlier I was hoping he would have done a bit more work or at least had a section on the terminology used to refer to the works in question instead of ‘works of law’. E.g. Ceremonies, Customs, Sacraments? This would have added to his argument.

The book engages with many scholars who have done work on the patristics. Some of these works are surprisingly contemporary, but others are a bit obscure. This shows Thomas has researched the topic to a good degree because I don’t think these books are easily accessible. Personally I had to go into a bit of trouble to find Justin Martyr’s – Dialogue in the Greek. Thomas has looked for the documents in their original language/translation for each.

Overall, in my opinion his readings and summary are in my opinion well founded and defendable. I commend this book for wide academic readership. I’d expect summaries of its findings would be helpful for students of early church history and Paul.

Further Notes

A few things to note regarding works of law;

- The law of Moses contains many commands (613!?), some of which regard intent (e.g. to love, to honour), others are prohibitions (e.g. ‘do not steal’) and others like the ‘works of law’ refers to the actions and deeds commanded in the law of Moses. The very expression highlights it concerns the commands the Jews ought to do, not specifically those they must not do.

- From 4QMMT (link) it seems apparent that they believed only the practice of ‘some works of law’ would avail for their future justification. Hence they believed not all of the ‘works of law’ were needed. Highlighting that some Jewish groups, I think including the Judaisers Paul was dealing with, believed they didn’t have to obey the whole law of Moses to be counted righteous, only a subset. This understanding accounts for their praxis and Paul’s opposition in Gal 3.10; 5.3 (Cranford, The Possibility of Perfect Obedience: Paul and An Implied Premise in Galatians 3:10 and 5:3) and the synecdoche held by the Jews Paul is opposing in Rom 9.32; 10.5.

- The verses which say ‘no flesh will be justified by works of law’ (Rom 3.19-20; Gal 2.14-16) as DeSilva notes comparing it to Ps 143.2 (p240-241, DeSilva, NICNT Galatians) is altered and qualified in two ways. Thus it is not universalised. First, When Paul refers to ‘flesh’ (lit. Sarx, word study here), he often compares it to those in the Spirit (e.g. Rom 8.1-9), which might explain why Lk 1.5-6 records Zechariah and his wife as ‘both righteous before God, walking blamelessly in all the commandments and statutes of the Lord’. In dealing with the supposed contradiction between Lk 1.5-6 and Ps 143.2, I suggest Paul’s meaning to be only people (in this case the Jews) in the flesh were not justified by works of law. This distinction provides a better fit IMO with the anthropology evidenced by the early patristics and scripture more broadly. “Second, Paul adds (and indeed foregrounds by stating ahead of the verb it qualifies) the phrase ‘on the basis of Torah-prescribed works,’ which makes his claim quite different from that of the psalmist.” (p241, ibid). Which is evidenced by Paul saying ‘the law speaks to those under the law’ in Rom 3.19 and ‘how can you force Gentiles to live like Jews’ in Gal 2.14.

- Again from 4QMMT describes the works of law as ‘good and beneficial for you and your people’. This expression does not expand the meaning of ‘works of law’ to include ‘good works’ in general. Rather it states their practice will promote their good health and will secure the likelihood of future justification. The later references to ‘upright and good’ again do not expand the meaning of ‘works of law’ to include ‘good works’, rather they indicate the Jews believed the law of Moses was the morally good and right thing to do (Same also for Rom 9.11). As stated by an increasing number of contemporary scholars, Paul distinguishes between ‘works of law’ and ‘good works’ more broadly.

In all this, my point is that from what I know of the early patristics, their understanding of ‘works of law’ is a tenable interpretation of the Paul’s meaning. Thus appropriate interpretative weight ought to be given it according to Thomas’ fire and smoke analogy.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2019. All Rights Reserved.