This small book is an excellent summary of NT Wright’s take on Paul’s theology. In it you will get a breakdown of key elements in Paul’s theology. It has all the elements one would expect coming from the New Perspective on Paul, with Wright’s particular spin on it.

This small book is an excellent summary of NT Wright’s take on Paul’s theology. In it you will get a breakdown of key elements in Paul’s theology. It has all the elements one would expect coming from the New Perspective on Paul, with Wright’s particular spin on it.

- Link: Amazon

- Length: 195

- Difficulty: Medium

- Topic: Theology, Paul

- Audience: Educated Christians, Lay Ministers

- Published: 2009

In this book Wright develops a framework for understanding Paul. Essentially he has reverse engineered Paul’s theology from his scriptures and broken it down into explainable parts. These parts essentially form the competing worldviews of his time, key elements of his theology and beliefs.

In this review I have first attempted to explain his approach in order to make sense of his argument. Then I step you through his book with this in mind. Basically if you read this review you will have a good understanding of NT Wright’s understanding of Paul.

This post is one of my book reviews.

Contents

Wrights Perspective on Paul

As I’ve mentioned in a previous review on Wright, he approaches scripture in different ways than I am used to. I’ll go into a little more detail on this now.

Wright operates at a deeper than normal level in Paul’s thought. This I find is both a strength and weakness.

| Paul’s words (what he says) | Most theologians |

| Paul’s intention (what he wants to achieve) | Most theologians |

| Paul’s theology (how he thinks) | NT Wright |

| Paul’s worldview (framework about the world) | NT Wright |

This doesn’t mean he is wrong, rather often he is simply speaking about different things than other people are when they consider the text. Wright generally considers big picture issues, other interpreters perhaps the textual details.

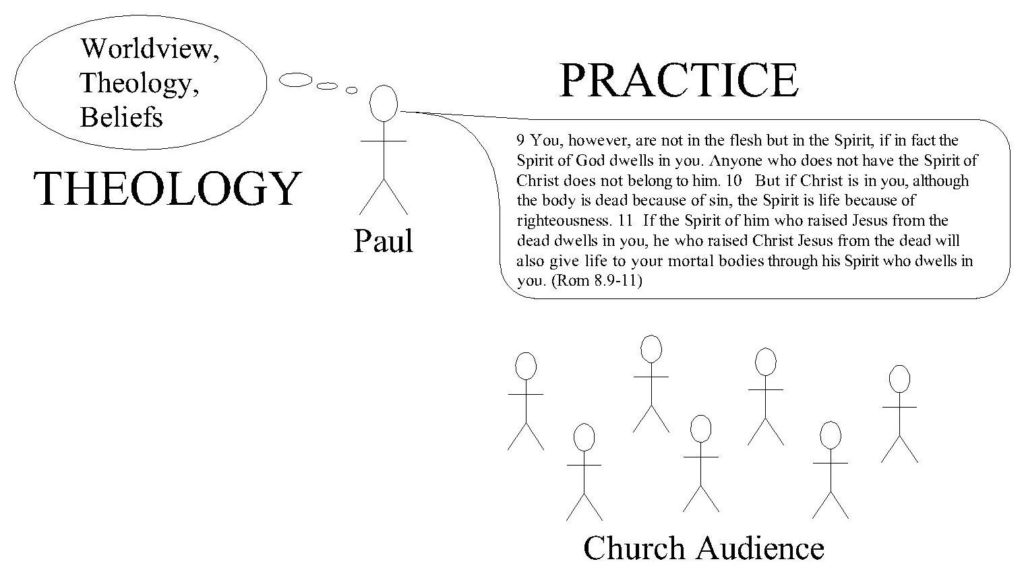

It’s better to understand Wright explaining Paul’s explanatory system of beliefs which frame and give context to all he writes.

It’s better to understand Wright explaining Paul’s explanatory system of beliefs which frame and give context to all he writes.

I created a series previously called explanatory functions, hopefully explaining that most theological systems are working from some assumed theory for how they then go and interpret scripture.

Wright likewise is operating at a deep level in Paul’s thought in order to explain Paul’s explanatory system. This is how Paul comes to speak and write about the things he does and the way he does them.

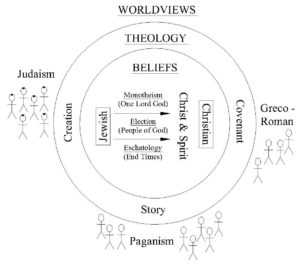

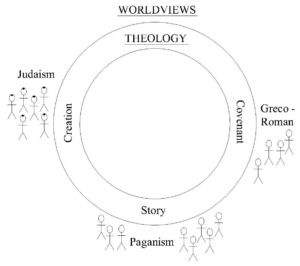

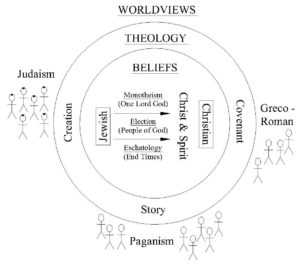

Worldview, Theology and Symbols

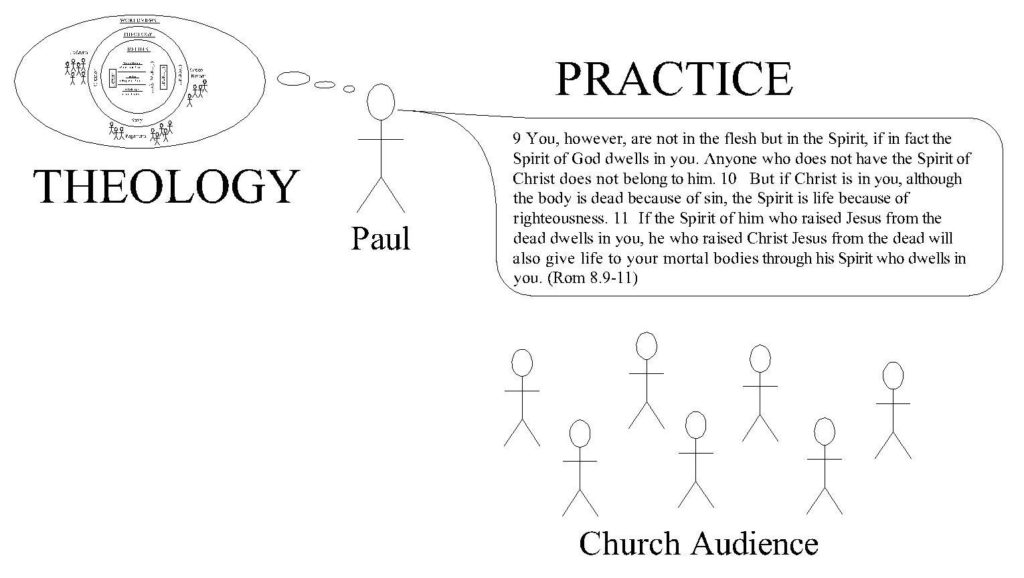

The key components of each of these in Wright’s book are: Worldviews, Theology and Beliefs. Wright goes into much greater detail in his tome, Paul and the Faithfulness of God. But this book is a much shorter read, but it’s still quite heavy. The following diagram is my summary of what Wright says is Paul’s explanatory system. In his book Wright moves from the outside, in towards the centre.

In his own words Wright says;

Let me then outline the argument of this book. The first chapter forms a general introduction, after which the next three chapters look at major Pauline themes which have been highlighted in some recent study, and which allow us to put down some preliminary markers about the way Paul’s mind worked. Then the fifth, sixth and seventh chapters form a miniature systematic account of the main theological contours of Paul’s thought. A final chapter looks more briefly at some key themes which our study may place in a new light. (x)

This hopefully will help you understand what Wright is talking about and put my comments in some sort of context.

Part I: Themes

1 Paul’s World, Paul’s Legacy

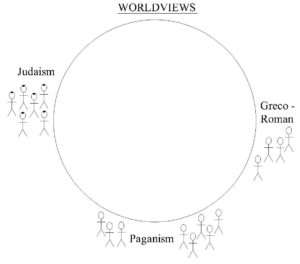

Wright begins explaining the three worlds of Paul. The first world is Second Temple Judaism. Under foreign rule. Anticipating a great redemptive act where God would restore them to their former glory. The second is the Greek world. This permeated the world, not in the least by the common vernacular, Koine Greek, and their various philosophies. The third is the Roman world, they were in political power, ruling over the people and trying to maintain peace. Wright says each of these influence Paul.

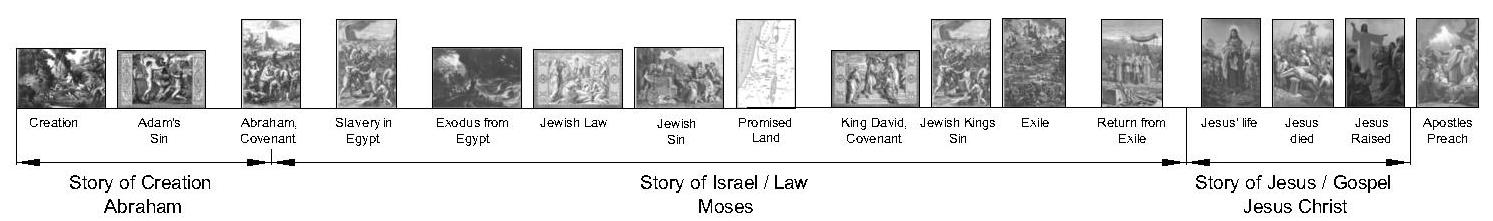

These worldviews lead Wright to speak of the different narratives each had. Their way of explaining chief questions of: who are we? Where are we? What’s wrong? What’s the solution and what time is it? He then explains that narrative thought is one of the primary building blocks of the new perspective on Paul.

The turn to narrative is, in fact, one of the most significant developments which the ‘new perspective’ revolution has precipitated, going far beyond anything Sanders himself said or (I believe) thought. I want to insist that this be seen both as part of the developing ‘new perspective’ and as a central, not merely illustrative or peripheral, element in Paul. (7)

For Paul, the story of Jesus, the gospel is his central focus and what explains all the above questions.

I want to insist that Paul’s whole point is precisely that with the coming, the death and the resurrection of Jesus the Messiah a new chapter has opened within the story in which he had believed himself to be living, and that understanding what that story is and how this chapter is indeed a radically new moment within it provides one of the central clues to everything else he says, not least the questions of justification and the law upon which the ‘perspective’-battles have been so often fought out. Refusing to admit narrative into this debate is therefore like refusing to put petrol in a car because you know that what you need to drive is tyres and a steering wheel. (9)

The remainder of the chapter deals with critics of narrative theology. Wright handles himself quite well explaining the value of looking at Paul through the framework of salvation history and these competing worldviews.

2 Creation and Covenant

In this chapter Wright surveys three large texts of Paul’s (Colossians 1:15–20, 1 Corinthians 15 and Romans 1–11), attempting to show how the underlining themes of Paul’s narrative theology consist of the interrelationship of creation and covenant.

I have now made the case for saying that the themes of creation and covenant, rooted in the Old Testament and developed within second-Temple Judaism, remained basic within the very Jewish thought of Paul. We can see him developing them in various ways, but he has not abandoned them in favour of some different overarching scheme. In particular, as we have seen, he believes that Israel’s God, the creator, has acted decisively to fulfil the covenant promises and so to renew both covenant and creation. Paul thereby understands himself to be living at a different moment in the story, though there are partial parallels within the inaugurated eschatology we find at Qumran. The new age has already begun, though the old age continues alongside it. That in turn generates both Paul’s vision of the church and the problems he addresses within it (33)

Wright defends himself later on.

These rich and dense themes [Creation, Covenant, Christology], as I said in the first chapter, cannot be appreciated by the kind of minimalist exegesis which tries to apply the laws of mathematics or engineering to the study of ancient texts. Exuberant writing calls for exuberant exegesis: not, of course, uncontrolled or fanciful exegesis, but an exegesis which pays attention to the proper controls, which are neither narrow lexicography nor philology, important though those are, but the wider rules of narrative discourse. (45)

In this chapter he says some interesting stuff about evil (sin) and grace. Wright describes the problem of sin;

The particular solution God proposes … shows that what is wrong concerns, in a central way,

[1] the fracturing of human relationships and

[2] the fracturing of the relationship between humans and the non-human creation.

And the particular faith for which God calls indicates, as Romans 4 draws out,

[3] that at the core of the problem is the failure of humans to trust God, to give him praise and honour as the all-powerful creator. (34)

We should note from the onset he is not so much concerned about personal guilt over sin or salvation for individuals. This leads the many reformed to critique him because he is not aligning to their frameworks.

Much later Wright will say;

The point of election always was that humans were sinful, that the world was lapsing back into chaos, and that God was going to mount a rescue operation. That is what the covenant was designed to do, and that is why ‘belonging to the covenant’ means, among other things, ‘forgiven sinner’. (121)

He then goes on from page 34 to explain this three fold understanding of the problem of sin was well understood by the Judaism. In particular they summed up sin as idolatry.

Regarding grace Wright looks to Christ’s representative death and says;

In both creation and covenant, grace perfects or completes nature not simply by topping it up but by judging it, condemning the evil which has infected it, and then renewing it. This, of course, is precisely the model offered by the representative death of Jesus the Messiah, who from Paul’s perspective offered to God the perfect obedience Israel should have offered, and thereby fulfilled on behalf of Israel as well as the world the rescue operation the covenant had always envisaged. (37)

If we apply Barclays taxonomy of perfections we could say Wright is highlighting incongruence, priority, arguably superabundance, effect and in Paul’s understanding of his apostleship reciprocity.

If we apply Barclays taxonomy of perfections we could say Wright is highlighting incongruence, priority, arguably superabundance, effect and in Paul’s understanding of his apostleship reciprocity.

3 Messiah and Apocalyptic

Wright argues that Paul is very much a Jewish thinker. Surprise surprise for a ex-Pharisee, Hebrew of Hebrews. The Old Testament scriptures and many Jews of the Second Temple period expected the coming of the promised Christ and what he would do.

First, we are talking about a royal Messiahship. The Messiah is Israel’s true king; hence also, since Israel is the people of the one creator God, he is the world’s true Lord. Paul, we should note, shows no interest in a priestly Messiah such as we find in some Qumran texts alongside the king.

Second, the Messiah will successfully fight Israel’s great and ultimate battle against the forces of evil and paganism.

Third, the Messiah will build the Temple, the house to which Israel’s God will at last return and live.

Fourth, the Messiah will thus bring Israel’s history to its climax, fulfilling the biblical texts regarded in this period as messianic prophecies, and usher in the new world of which prophets and others had spoken.

Fifth, the Messiah will act in all this as Israel’s representative, like David fighting Goliath on Israel’s behalf.

Sixth, in another sense the Messiah will act as God’s representative or agent to Israel and hence to the world.

There is no time to spell these out, but each is attested here and there in second-Temple readings of the biblical texts, and each is, as I shall now suggest rather than argue in detail, solidly present in Paul’s use of Christos for Jesus. (p43)

In addition to this Wright gives a description of Paul’s understanding of Apocalyptic.

Which has more to do with God’s coming and climax of salvation history than what for example what Ernst Käsemann, J. Louis Martyn and Douglas Campbell argue for.

4 Gospel and Empire

Wright goes on to spend a little time on how Paul’s gospel interacted with the competing worldviews of his time. In this chapter Wright brings together what he has said so far and applies it to Paul’s subversive gospel message.

According to Paul’s view of creation, the one God was responsible for the whole world and would one day put it to rights. According to his covenant theology, this God would rescue his people from pagan oppression. His messianic theology hailed Jesus as King, Lord and Saviour, the one at whose name every knee would bow. His apocalyptic theology saw God unveiling his own saving justice in the death and resurrection of the Messiah. At every point, therefore, we should expect what we in fact find: that, for Paul, Jesus is Lord and Caesar is not. (69)

This is not to say the gospel only responded to the Roman claim of Lordship and salvation. Note in the comment his attention to the covenant. Wright also describes the gospel fulfilling many OT expectations. Not in the least the Isaianic promises of the servant songs, the prophecies of Jeremiah and Ezekiel.

His strongest support for arguing the gospel message intentionally opposes Caesars claim as Lord and Saviour comes from Romans 1.

In fact, the whole introduction to the letter contains so many apparently counter-imperial signals that I find it impossible to doubt that both Paul and his first hearers and readers—in Rome, of all places!—would have picked up the message, loud and clear. Jesus is the world’s true Lord, constituted as such by his resurrection. He claims the whole world, summoning them to ‘the obedience of faith’, that obedient loyalty which outmatches the loyalty Caesar demanded. The summons consists of the ‘gospel’, a word which, as is now more widely recognized, contains the inescapable overtones both of the message announced by Isaiah’s herald, the message of return from exile and the return of yhwh to Zion, and of the ‘good news’ heralded around the Roman world every time the anniversary of the emperor’s accession, or his birthday, came round again. (76)

Part II: Structures

Wright explains the core of his argument for Paul’s theology. The rethinking, reworking and reimagining of central tenants of Judaism around key elements of Christianity. Christ and the Spirit.

When Jewish writers have taken it upon themselves to summarize what Jews believe, they have focused on two topics, with a third not far behind. The main two are God and God’s people: monotheism and election. When you put monotheism and election together, and then look at the present state of the world and of God’s people, you will quickly come up with a third, namely eschatology. … Hence the threefold pattern: one God, one people of God, one future for God’s world.

My proposal in this second main part of the book is that Paul’s thought can best be understood, not as an abandonment of this framework, but as his redefinition of it around the Messiah and the Spirit. (84)

Wright argues the central tenets of Judaism are monotheism (One Lord God), election (The people of God), and inaugurated eschatology (the end times which have now broken into the present). (Note: Wright does not go out of his way to explain the Jewish understanding of sin and grace. This stands in contrast to how the reformed typically frame Paul.)

5 Rethinking God

Wright begins by describing the roots Jewish creational and covenantal monotheism. He discusses the implications these have on how the Jews thought of the problem of evil. Both in creation, the nations and themselves as God’s people.

He then goes on to show how Paul has rethought his understanding of monotheism through Christ and the Spirit from selection of passages including Colossians 1-2, 1 Corinthians 1-3 and 8.1-6.

In his book, Wright occasionally comments on the problem of sin and evil and how God deals with it. These warrant highlighting. Wright seems to be working predominately with a Christus Victor understanding of atonement here.

But in summing up this section on the christological redefinition of monotheism we must inevitably say a word about the cross. For Paul this was of course the ultimately shocking and ultimately glorious thing:

that in becoming human to fulfil his own promises, Israel’s God, the creator, had chosen to die on a cross.

The cross became, for Paul, the fullest possible revelation of both the love and the justice of God, and then, in its outworking, the extraordinary saving power of God, defeating the powers that held people captive in pagan darkness and breaking the long entail of human sin. The cross is the climactic moment in Paul’s redefinition of election. (95)

Wrights discussion focusses on how Paul understood monotheism through Christ and the Spirit. He pulls together several themes relating to the Spirit in Romans 8.

This remarkable passage leads the eye naturally to Romans 8, where again Paul draws heavily on the motif and the language of the Exodus. God’s people, set free from slavery, must not think of going back to it, but must rely on the presence and leading of God as they go on to their inheritance. Within the original Exodus-story, of course, the people were given the tabernacling presence of God, despite their rebellion and sin, as their guide and companion. In Paul’s retelling of the story, the Spirit takes the place of the Shekinah, leading the people to the promised land, which turns out to be, not ‘heaven’ as in much Christian mistelling of the story (‘heaven’ is not mentioned here or in any similar passages), but the new, or rather the renewed, creation, the cosmos which is to be liberated from its own slavery, to experience its own ‘exodus’. (98)

Note the emphasis on the OT narrative, the exodus typology and how these relate to the Christian experience with the Spirit.

6 Reworking God’s People

In this next section Wright focusses on election and God’s people. Again Wright is describing Paul’s revised thinking concerning the people of God. In the OT God chose Israel to be his people. In the New Testament, all nations, Jews and Gentiles make up the elect.

For most this is one of the more controversial chapters because Wright speaks about justification by faith and the righteousness of God.

There is enough there to keep us going all day, but let me simply spell out three points.

First, I have translated pistis Christou and similar phrases as a reference, not to human faith in the Messiah but to the faithfulness of the Messiah, by which I understand, not Jesus’ own ‘faith’ in the sense either of belief or trust, but his faithfulness to the divine plan for Israel. I mentioned this in an earlier chapter in connection with Romans 3, to which I shall return presently.

Second, the passage works far better if we see the meaning of ‘justified’, not as a statement about how someone becomes a Christian, but as a statement about who belongs to the people of God, and how you can tell that in the present. That is the subject under discussion.

Third, the point of ‘works of Torah’ here is not about the works some might think you have to perform in order to become a member of God’s people, but the works you have to perform to demonstrate that you are a member of God’s people.

These works, Paul says, simply miss the point, as Psalm 143:2 had indicated, partly because nobody ever performs them adequately, and partly because, here and elsewhere, works of Torah would simply create a family which was at best an extension of ethnic Judaism, whereas God desires a family of all peoples, the point which is repeatedly emphasized in Galatians 3. (112f)

the main theme is the fact that God has one family, not two, and that this family consists of all those who believe in the gospel. Faith, not the possession and/or practice of Torah, is the badge which marks out this family, the family which is now defined as the people of the Messiah. (113)

Wright articulates a consistent view with his other writings (e.g. What Saint Paul Really Said, Paul and the Faithfulness of God), that justification by faith relates to the identification of the covenant people of God. By faith and not by works of law. He argues Gal 2.11-21; Rom 3.20, 27-30; ought to be understood this way, in which I am in agreement. As noted in another series this understanding was reflected early on in the church.

He also argues the righteousness of God (e.g. Rom 1.16-17; 3.5, 21-22; 2 Cor 5.21) in Paul refers to God’s covenant faithfulness to his promises as he does in What Saint Paul Really Said. His argument is supported by his understanding of how the Jews of the second temple understood God’s righteousness and by the context of what Paul says in his letters. Note my argument for the relationship between covenant and righteousness here.

Second, the passage [Gal 2.11-21] works far better if we see the meaning of ‘justified’, not as a statement about how someone becomes a Christian, but as a statement about who belongs to the people of God, and how you can tell that in the present. That is the subject under discussion. Third, the point of ‘works of Torah’ here is not about the works some might think you have to perform in order to become a member of God’s people, but the works you have to perform to demonstrate that you are a member of God’s people. (112)

However as I have noted elsewhere (here and here) Paul does numerous times associate justification with sinners becoming righteous (e.g. Rom 3.23-24; 5.1, 8-9, 19; 1 Cor 6.9-11; Tit 3.3-7). Note in many cases here Paul does not say ‘by faith’. For me this indicates a distinction, as I’ve noted with Stendahl. These passages do not thereby imply Wright is wrong on justification, rather for me justification can be understood in different ways and of course this largely depends on the context.

For Wright, these simply relate to the declaration made immediately after conversion. I’m actually comfortable with this, but I do think Rom 5.19 is especially clear justification can relate to sinners being made righteous.

7 Reimagining God’s Future

Like the two previous chapters Wright will spend a little bit of time describing what the Jews of the second temple period thought about eschatology (e.g. Lk 24.21; Acts 1.6). He will refer to passages such as Dt 30 and Dan 9 as these carry a lot of weight for his understanding of the period and Paul.

He then begins to wrap this understanding around Christ and the Spirit. The most obvious eschatological aspect relating to Christ is his second appearing and judgment. Jesus will return to judge. God’s people will reign with him, restored as God’s image bearers and second in charge of creation. The role of the Spirit in the end times is obviously associated with resurrection and the redemption of all creation.

This is a brief quote relating to Wright’s reading of Paul in Romans 6-8. Normally I would interpret the main points of these chapters as;

| Rom 6.1-23 | Rom 7.1-25 | Rom 8.1-11 | Rom 8.12-39 | |

| My reading | How believers ought to live since they are under grace and not under the law of Moses. | Is the law of Moses sinful?

The question of non-Christian Jews under the law and the power of sin. |

Believers freed from sin and encouraged to live by the Spirit, putting to death the deeds of the body. | We are God’s Sons suffering now, but waiting in hope for the future redemption. |

Wright however looks deeper and says;

To recapitulate the point: in Romans 6 God’s people come through the waters which mean that they are delivered from slavery into freedom;

in Romans 7:1–8:11 they come to Sinai only to discover that, though the Torah cannot give the life it promised, God has done it;

with the promise of resurrection before them, they are then launched onto the journey of present Christian life, being led by the Spirit through the wilderness and home to the promised land which is the renewal of all creation (8:12–30).

This is Paul’s version of the retold Exodus story, in loose parallel with the final chapters of the Wisdom of Solomon. It is based, as was Wisdom’s retelling, on a fresh reading of the stories of Adam and Abraham (Romans 5 and Romans 4 respectively, out of narrative sequence because of the rhetorical needs of the argument at this point).

And this story continues to inform his thinking at many other points. (138)

In all these chapters Wright reads into it the Exodus narrative reworked around the Christian experience.

| Rom 6.1-23 | Rom 7.1-25 | Rom 8.1-11 | Rom 8.12-39 | |

| My reading | How believers ought to live since they are under grace and not under the law of Moses. | Is the law of Moses sinful?

The question of non-Christian Jews under the law and the power of sin. |

Believers freed from sin and encouraged to live by the Spirit, putting to death the deeds of the body. | We are God’s Sons suffering now, but waiting in hope for the future redemption. |

| Wright’s reading

(Exodus Story) |

Baptism, Israel passing through Red Sea. | Israel at Mount Sinai receiving the law | Israel travelling through the wilderness | Israel entering into the promised land |

I guess the big question is, “Is Paul intentionally adapting the Exodus story to his application here or are these references just incidental to his original intention or can it be both?” I think Wright would say it’s both.

I wonder how someone could do this even if it was intentional to do both? Did Paul say to himself I want to make a series of points and instructions which loosely follow the Exodus story?

While in Romans 8 I do see a fair amount of typology being employed to describe the Christian experience in the Spirit, I find it I find this a bit of a stretch to apply the whole narrative to chapters 6-8.

8 Jesus, Paul and the Task of the Church

Wright in this chapter largely discusses the relationship between Jesus and Paul, and then Paul’s understanding of his own role in God’s purposes and what he intends to achieve with his writings.

I quite like Wright’s depiction of Paul’s relationship to Jesus. He first gives a series of similar examples.

[The conductor’s] job is to play the music the original composer has written. The doctor takes the results of the research and applies them to the patient. Her job is not to do more research on the topic; or, if she thinks it is, it isn’t because she is being loyal to the original researcher but because she is being disloyal. The builder takes the plans drawn up by the architect and builds to that design. (155)

Wright discusses some of what he argues in Jesus and the Victory of God.

I have argued elsewhere that Jesus believed himself to be bringing to its great climax, it’s great denouement, the long story of yhwh and Israel, which was the focal point of the long story of the creator and the world. I have proposed that he believed himself to be embodying both the vocation of faithful Israel and the return of yhwh to Zion, drawing on to himself not only the destiny of God’s true Servant but, if we can put it like this, the destiny of God himself. (156)

He then moves on to Paul, and his understanding of his role as an apostle.

Paul, too, believed himself to have a special, unique role within the overall purposes of Israel’s God, the world’s creator; and

that role was precisely not to bring Israel’s history to its climax—that had been done in the death and resurrection of the Messiah—but rather to perform the next unique task within an implicit apocalyptic timetable, namely to call the nations, urgently, to loyal submission to the one who had now been enthroned as Lord of the world.

Paul believed that it was his task to call into being, by proclaiming Jesus as Lord, the worldwide community in which ethnic divisions would be abolished and a new family created as a sign to the watching world that Jesus was its rightful Lord and that new creation had been launched and would one day come to full flower. (157)

The remainder of the chapter discusses Paul’s ‘redefinitions’ in practice.

He says Paul wrote in such a way that his audiences would learn the principles by which they ought to make ethical and life decisions, not simply give them a new set of rules. He says a lot about church unity. He sums up much of what he wrote of earlier and gives a brief description of how he breaks down the biblical story into six acts. He lastly concludes with the primary motivation – love.

Recommendation

This book is the more readable version of Paul and the Faithfulness of God. That being said, while it is much smaller, the reading itself is dense. Wright writes in broad sweeping and colourful language. Personally I didn’t find it hard to get through.

His treatment of the Pauline corpus refuses to follow a straight line. Simply going to the scripture index at the back will not help all that much in order to work out how he interprets certain passages. The justification passages for example. Reading the whole book is the go to understand how his comments on various passages fit.

The book contains all the New Perspective elements one would expect: Narrative theology, Righteousness of God, covenant faithfulness, pistis Christou, Christus Victor theory of atonement, gospel, justification by faith and the end times judgment. So it’s a good goto for Wright’s theology.

As with much of Wright’s stuff, he is operating at a different level than most. After reading a bit of him this can get a bit boring. He doesn’t provide exhaustive arguments for his interpretations. Which can be a pain if your peers don’t like him much, you have to do this work for yourself.

Overall however, I’m glad I read the book. Through it I better understood the context of much of Wright’s argument and am now more careful to pay attention to the various themes in Paul’s epistles.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2017. All Rights Reserved.