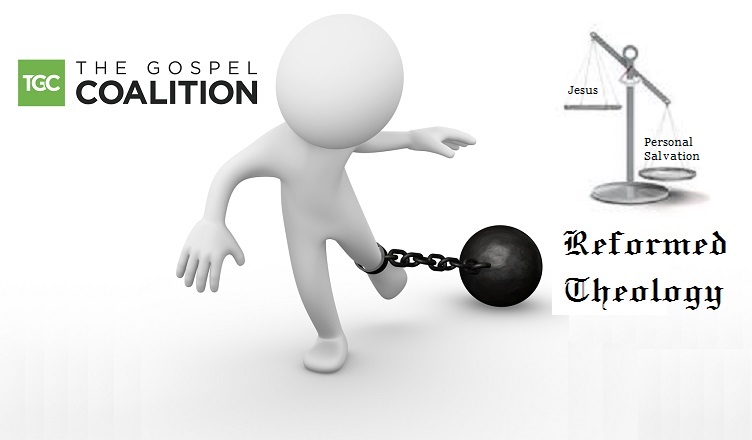

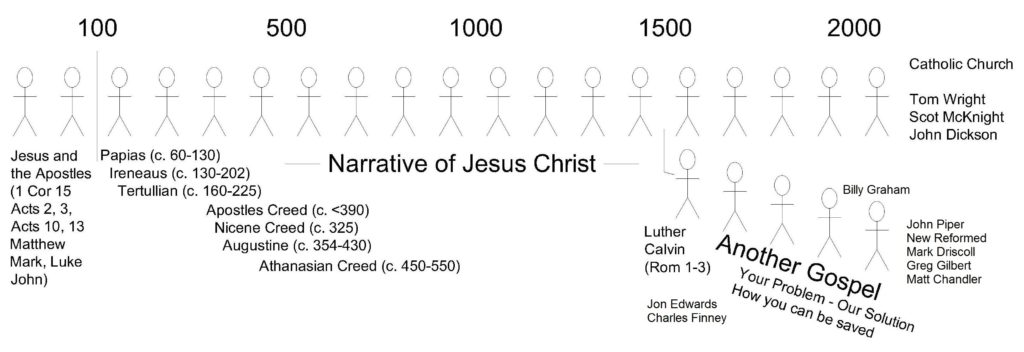

During the reformation Luther ‘discovered’ or should I say created a brand new understanding of the gospel through his reading of Romans 1-4. In this book – ‘What is the Gospel?’, Gilbert outlines the same soterian gospel by stepping us through Romans. This is a very clearly written book. This review questions whether is this what Saint Paul really said in Romans 1-4 and if this is his gospel.

During the reformation Luther ‘discovered’ or should I say created a brand new understanding of the gospel through his reading of Romans 1-4. In this book – ‘What is the Gospel?’, Gilbert outlines the same soterian gospel by stepping us through Romans. This is a very clearly written book. This review questions whether is this what Saint Paul really said in Romans 1-4 and if this is his gospel.

- Link: Amazon

- Length: 121

- Difficulty: Easy-Popular

- Topic: Gospel

- Audience: Mainstream Christians

- Published: 2010

The concept of a square is easy enough to understand, but the question I’m asking is does it fit into the hole properly? Does Gilbert’s gospel adequately account for what scripture says about the gospel?

My belief is that Gilbert has extensively modified Romans 1-4 and cut it down to suit his own predetermined understanding of the gospel. I don’t think he has given us the historical and apostolic gospel. His gospel is very popular in evangelical circles (e.g. Carson endorses it in the Foreword), but it’s unbiblical.

Here is a link to my understanding of the gospel. I suggest you read it to compare and contrast my understanding with his. Here is a link to my series on Romans. I suggest you have a gander to again see my understanding of Romans 1-4.

This post is one of my book reviews.

Overview

Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Finding the Gospel in the Bible

- 2 God the Righteous Creator

- 3 Man the Sinner

- 4 Jesus Christ the Savior

- 5 Response—Faith and Repentance

- 6 The Kingdom

- 7 Keeping the Cross at the Center

- 8 The Power of the Gospel

Gilbert’s Introduction

Gilbert’s introduction highlights that if you were to ask several christians what the gospel is, you would invariably get many different answers.

Ask any hundred self-professed evangelical Christians what the good news of Jesus is, and you’re likely to get about sixty different answers. Listen to evangelical preaching, read evangelical books, log on to evangelical websites, and you’ll find one description after another of the gospel, many of them mutually exclusive. (17)

This is common in books about the gospel. He devotes a couple pages to a variety of different takes on it, including what seems like NT Wright’s depiction of the gospel.

The gospel itself refers to the proclamation that Jesus, the crucified and risen Messiah, is the one, true, and only Lord of the world. Good news! God is becoming King and he is doing it through Jesus! God’s justice, God’s peace, God’s world is going to be renewed.

And in the middle of that, of course, it’s good news for you and me. But that’s the derivative from, or the corollary of the good news which is a message about Jesus that has a second-order effect on me and you and us.

But the gospel is not itself about you are this sort of a person and this can happen to you. That’s the result of the gospel rather than the gospel itself. . . . Salvation is the result of the gospel, not the center of the gospel itself. (18)

Personally I think Gilbert wrote parts of this book with the intention of undermining Wrights depiction of the gospel.

Gilbert states several aims of his book. He hopes to focus our worship on Jesus. He wants to give his readers confidence to share the gospel with others. He hopes we will see its importance for the church. He hopes we will be more inclined to speak of the difficult parts of the message many are tempted to soften. Lastly he hopes to get our attention. To apply the gospel to ourselves. These are all great aims.

Gilbert’s Method

Gilbert in his introduction discusses how to go about working out what the gospel is from scripture.

But where do we go in the Bible to find that? I suppose there are several different approaches we could take. One would be to look at all the occurrences of the word gospel in the New Testament and try to come to some sort of conclusion about what the writers mean when they use the word. Surely there are a few instances where the writers are careful to define it. There could be important things to learn from this approach, but there are drawbacks, too. One is that often in the New Testament a writer obviously intends to give a summary of the good news of Christianity, yet he doesn’t use the word gospel at all. (26)

How can one objectively approach the scriptures to understand what the apostles believed the gospel is without imposing our own bias’ on the solution? Personally I think this is difficult because most people have some sort of bias and axe to grind. Gilbert and myself are no different.

Gilbert dismisses the word study / search method because he claims sometimes the New Testament authors could write about the gospel without ever mentioning it. Personally I think looking at all the occurrences of the word ‘gospel’ is the most objective manner to go about the question.

Yes, the authors of the NT can and do speak about the gospel without using the word ‘gospel’ (‘good news’, etc. e.g. 2 Pet 1.19-21; 1 Jn 1.1-3). But part of the purpose of doing a word search is to learn about the various word groupings associated with the primary word. Once these words are worked out these associated words can be used to find other instances where the concept is being spoken about, even when the word itself is not used. I call this a two pass word study. I believe this is one of the more objective approaches to answering the question ‘what is the gospel’ and what I used in my series.

Instead Gilbert comes up with another method.

Let me suggest that, for now, we approach the task of defining the main contours of the Christian gospel not by doing a word study, but by looking at what the earliest Christians said about Jesus and the significance of his life, death, and resurrection.

If we look at the apostles’ writings and sermons in the Bible, we’ll find them explaining, sometimes very briefly and sometimes at greater length, what they learned from Jesus himself about the good news. Perhaps we’ll also be able to discern some common set of questions, some shared framework of truths around which the apostles and early Christians structured their presentation of the good news of Jesus. (26)

He assumes the gospel must be about ‘Jesus and the significance of his life, death and resurrection’. While these are quite plausible, I think he has already sacrificed objectivity in his study.

Coming from my own understanding of the gospel he has already ruled out the gospel can be the telling of the story of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. It has to be about the significance of those.

A subtle difference I know, but Gilbert has already given an implied criticism of Wright who makes big deal of another subtle yet important distinction saying, ‘Salvation is the result of the gospel, not the center of the gospel itself.’ Gilbert is in effect saying something almost opposite, ‘The life, death and resurrection of Jesus is not the gospel, it’s the significance of these for us that is the center’.

Gilbert goes on to say;

The Gospel in Romans 1–4

One of the best places to start looking for a basic explanation of the gospel is Paul’s letter to the Romans. Perhaps more clearly than any other book of the Bible, Romans contains a deliberate, step-by-step expression of what Paul understood to be the good news. (27)

So Gilbert chooses Romans 1-4, almost out of the air. A bunny out of a hat. He expects his readers to take it on faith that Romans 1-4 is the gospel and it’s yet to be seen these chapters are actually a good place where Paul speaks about ‘Jesus and the significance of his life, death and resurrection’.

So Gilbert chooses Romans 1-4, almost out of the air. A bunny out of a hat. He expects his readers to take it on faith that Romans 1-4 is the gospel and it’s yet to be seen these chapters are actually a good place where Paul speaks about ‘Jesus and the significance of his life, death and resurrection’.

Perhaps one might argue that Romans 1-4 is the gospel because Paul says he hopes to go to Rome to preach the gospel to them (Rom 1.13-15). But this does not necessarily mean what follows is the gospel. Rather he will delay that until he sees them in person. Paul afterward says he ‘is not ashamed of the gospel’ and again this does not necessarily imply what follows is the gospel. The fact is, Paul refers to the gospel many times in his epistles and when he does he doesnt necessarily go into a ‘deliberate, step by step expression’ of his gospel.

Gilbert’s Reading of Romans 1-4

I’ve broken down Gilbert’s reading of Romans into his four key steps, bolding what I think is important. As we go through I will compare and contrast his reading with what Paul actually says and does in Romans 1-4.

Let’s look at the progression of Paul’s thought in Romans 1–4.

First, Paul tells his readers that it is God to whom they are accountable. After his introductory remarks in Romans 1:1–7, (27)

Gilbert very briefly refers to Romans 1.1-7. These ‘introductory remarks’ actually say quite significant things about the gospel. Paul says of the gospel, it was ‘promised beforehand in the scriptures’, it ‘concerns [God’s] His Son’, Jesus was ‘descended from David’, Jesus is ‘declared to be the Son of God in power’, ‘by his resurrection from the dead’, and the gospel ‘brings about the obedience of faith’, ‘among all nations’. These seem quite significant to me and more than just ‘introductory remarks’ to pass by and virtually ignore.

Paul begins his presentation of the gospel by declaring that “the wrath of God is revealed from heaven” (v. 18). With his very first words, Paul insists that humanity is not autonomous.

We did not create ourselves, and we are neither self-reliant nor self-accountable. No, it is God who created the world and everything in it, including us. Because he created us, God has the right to demand that we worship him. (27)

Second, Paul tells his readers that their problem is that they rebelled against God. They—along with everyone else—did not honor God and give thanks to him as they should have. Their foolish hearts were darkened and they “exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things” (v. 23). (28)

As I mentioned before Gilbert assumes Romans 1-4 is the gospel. Here Gilbert says, ‘Paul begins his presentation of the gospel’ from verse 18, but provides no reason why we should think that or even why he thinks Romans 1-4 is the gospel. Again we have to take it on faith he is correct.

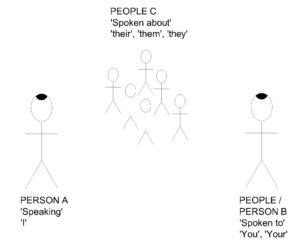

In his reading of Romans 1-4 Gilbert makes it very clear he thinks Paul is speaking to his readers. He says in three of the four steps, ‘Paul tells his readers’. Gilbert uses the pronouns ‘their’, ‘them’ and ‘they’ in the above quote to refer to the Roman audience. Gilbert likewise is keen to include readers of his book in this grouping as well (‘we’, ‘us’).

In his reading of Romans 1-4 Gilbert makes it very clear he thinks Paul is speaking to his readers. He says in three of the four steps, ‘Paul tells his readers’. Gilbert uses the pronouns ‘their’, ‘them’ and ‘they’ in the above quote to refer to the Roman audience. Gilbert likewise is keen to include readers of his book in this grouping as well (‘we’, ‘us’).

In my reading of Romans (see here and here) Paul is not actually speaking about his audience when he says, ‘their’, ‘them’ and ‘they’ in Romans 1. Paul is actually speaking about some group other than who he is speaking too. That’s how third person plurals work.

So my problems with Gilbert’s reading begin here. Paul is not telling his readers, ‘their problem is that they rebelled against God’. In fact, just a few verses earlier he says he is thanking God for their faith, which is being proclaimed in all the world (Rom 1.8). Quite the opposite.

Gilbert will continue on to sum up a large portion of Romans 1-3.

Gilbert will continue on to sum up a large portion of Romans 1-3.

For most of the next three chapters Paul presses this point, indicting all humanity as sinners against God. In chapter 1 his focus is on the Gentiles, and then in chapter 2 he turns just as strongly toward the Jews. (28)

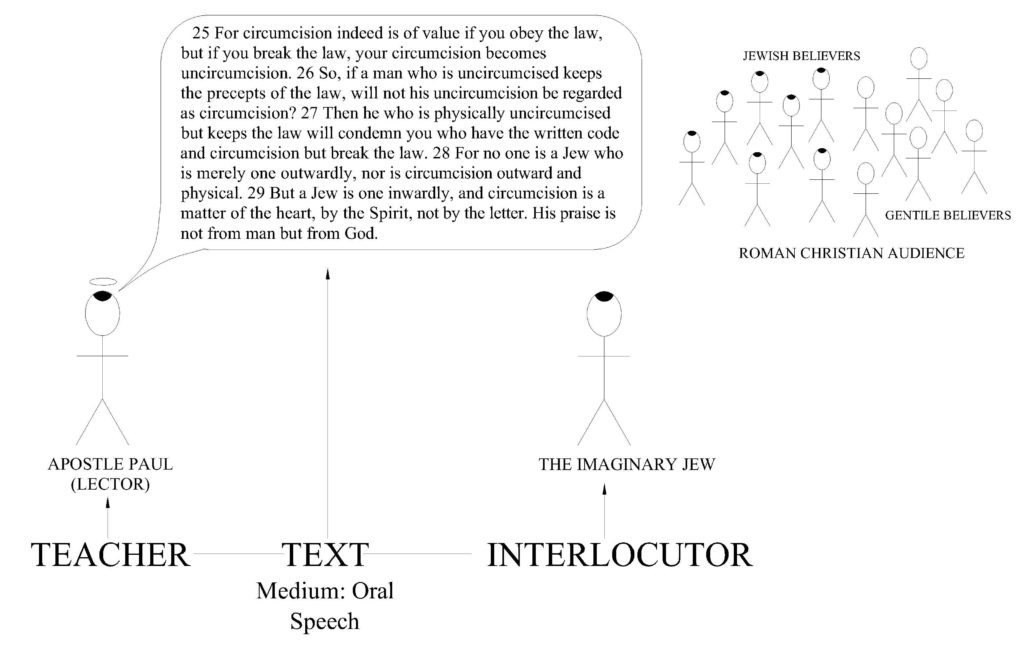

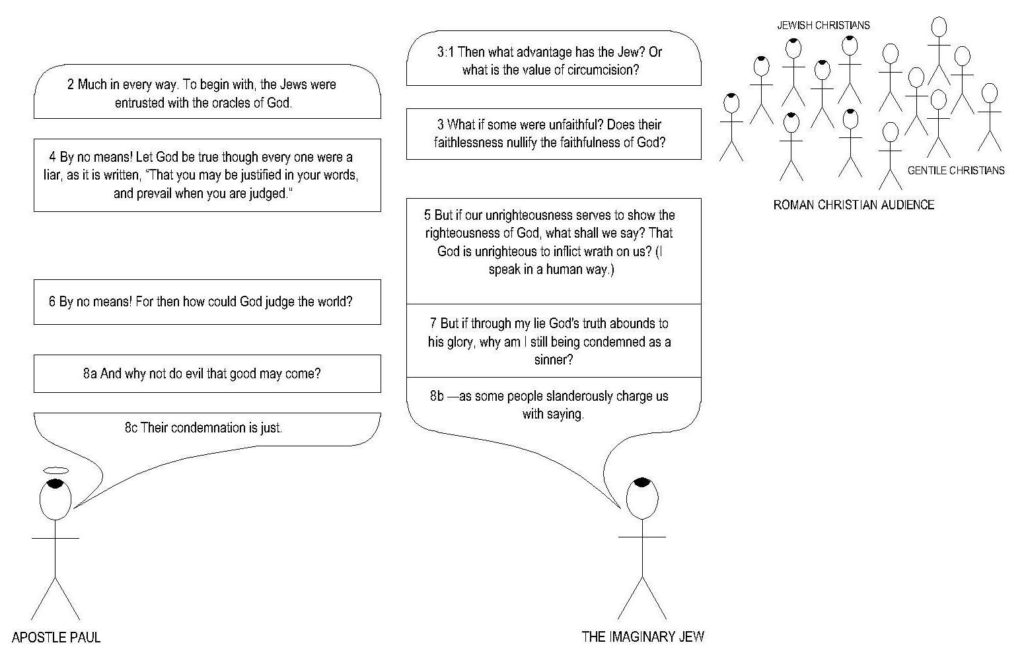

I find one of the most significant oversights of Gilbert’s in his reading of Romans 1-3 is he fails to incorporate the Jewish interlocutor in his understanding of Paul’s speech. In Romans 2.17 Paul is quite clear he is not in fact speaking directly to the Roman Christian audience, he is addressing a Jewish interlocutor.

The three facts:

- Paul is directly speaking to an imaginary Jew (Rom 2.17),

- Paul is responding to the imaginary Jew’s judgment on Gentiles (Rom 2.1-5), and

- Their background audience consists of Jew and Gentile believers (Rom 1.5-6, 8, 13-15; 7.1; 14.1f),

I think ought to influence how we interpret Paul’s main intentions in writing Romans 1-4. The following diagram shows the context Paul is speaking into in Romans 1-4.

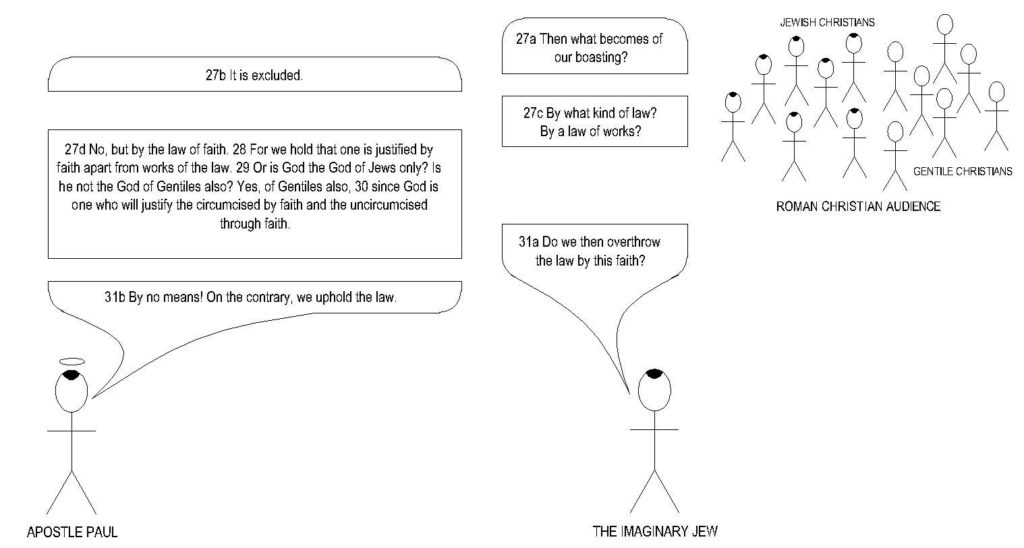

The dialogue between Paul and the imaginary Jew has two main rhetorical sections, where Paul is using a teaching device to put forward his argument. Romans 3.1-9,

And Romans 3.27-31.

Gilbert ignores these significant features in his reading. In my opinion all these above points I have raised pose significant problems for his reading of Romans 1-4.

If we move on to Gilbert’s remaining steps we learn a bit more about his understanding of Romans 1-4.

Third, Paul says that God’s solution to humanity’s sin is the sacrificial death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Having laid out the bad news of the predicament we face as sinners before our righteous God, Paul turns now to the good news, the gospel of Jesus Christ. …

So how does it happen? Paul puts it plainly in Romans 3:24. Despite our rebellion against God, and in the face of a hopeless situation, we can be “justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus.” Through Christ’s sacrificial death and resurrection—because of his blood and his life—sinners may be saved from the condemnation our sins deserve. (30)

Having explained the ‘bad news’ according to his reading of Romans 1-4 so far, Gilbert goes on to say God’s solution to humanity’s sin is the sacrificial death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. I agree, this is God’s solution to humanity’s sin. I’d even go so far to agree there is a general movement in Romans 1-3 describing the plight of unbelievers because they are sinners under God’s wrath.

This however isn’t the only part of what Paul says. It stands in contrast to the obedient (Jews and Gentiles) Paul keeps referring to and the number of Jew-Gentile rhetorical points he makes (Rom 2.6-11, 13-14; 25-29; 3.27-31).

From a strict reading of the Rom 3.21-26 text I note there are no references to Jesus’ life and resurrection. Gilbert’s stated reason for choosing Romans 1-4 is because it speaks about the significance of Christ’s ‘life, death and resurrection’. But where does the text refer to Christ’s life and resurrection here? Does the text satisfy Gilbert’s own criteria for choosing the passage?

Gilbert might read ‘pisteos Iesou Christou’ (Rom 3.22) to mean the ‘faithfulness of Christ’ which is understood to mean Christ’s obedience unto death, this I think refers in part to Jesus’ life. But I don’t think he does.

And the ‘redemption in Christ Jesus’ I think implicitly includes Christ’s resurrection, which based on the redemption/slave market imagery in Romans 6, but he doesn’t back himself up here either.

These are both important because Gilbert said he chose Romans 1-4 because it speaks about Jesus and the significance of his life, death and resurrection. The main question running through my head is:

‘Does Romans 1-4 qualify sufficiently to satisfy Gilbert’s own criteria for choosing this passage?’

Personally I’m not convinced it does. How much space does Rom 1-4 devote to Jesus? How much space does Rom 1-4 devote to the significance of his life and resurrection? If our answer is ‘not much’, then we have to reconsider Gilbert’s whole argument for Romans 1-4 and his gospel.

Gilbert has not acknowledged the gospel is witnessed to by the law and the prophets (Rom 3.21; cf. 1 Cor 15.3-5; ‘according to the scriptures’). This may seem to be a small thing, but Rom 1.2-3 and 3.21 both seem to me to relate to Paul’s ‘according to the scriptures’ references in 1 Cor 15.3-5. These argue for a rival framework from which to understand the significance of Christ’s life, death and resurrection – Gilbert ignores them.

Gilbert’s last step;

Finally, Paul tells his readers how they themselves can be included in this salvation. That’s what he writes about through the end of chapter 3 and on into chapter 4. The salvation God has provided comes “through faith in Jesus Christ,” and it is “for all who believe” (3:22). So how does this salvation become good news for me and not just for someone else? How do I come to be included in it? By believing in Jesus Christ. By trusting him and no other to save me.

“To the one who does not work but believes in him who justifies the ungodly,” Paul explains, “his faith is counted as righteousness” (4:5). (30)

Gilbert says, ‘Paul tells his readers how they themselves can be included in this salvation’. Like before, Gilbert has ignored Paul’s Jewish interlocutor (the person he is speaking to) and the fact that the Roman audience are believers already (Rom 1.8).

Paul’s readers don’t have to be ‘included in this salvation’ because they are already ‘in this salvation’.

Paul acknowledges this in Rom 4.23-5.2; etc.

Gilbert’s take on Romans 4.5 is popular among evangelicals, but I’m not convinced. As NT Wright has highlighted (in my series also) Abraham’s faith is in God’s promise of offspring (Rom 4.18). The ungodly who will be justified does not refer to Abraham (he already was right with God from Gen 12.4 onwards; cf. Gal 3.8-9; Heb 11.8). The ungodly refer to the Gentiles God promised who would be included in his worldwide family (Rom 4.9-12). Essentially Abraham’s faith was counted as righteousness because he believed God would justify the ungodly Gentiles. Thus receiving the covenant blessings of forgiveness and non imputation of sins the Jews typically received and also bringing them into his worldwide family.

Note: I’m not denying faith is instrumental when sinners are made right with God. I’m denying this is Paul’s point with his references to ‘justification by faith’ and ‘faith counted as righteousness’ in Romans 1-4. Both refer to the identification of the righteous (Jew and Gentile), not denoting the event where sinners become righteous. For more on this see my New Perspective page.

Gilbert’s Summary of the Gospel

After giving his reading of Romans 1-4 Gilbert boils down the four crucial questions and steps.

Now, having looked at Paul’s argument in Romans 1–4, we can see that at the heart of his proclamation of the gospel are the answers to four crucial questions:

- Who made us, and to whom are we accountable?

- What is our problem? In other words, are we in trouble and why?

- What is God’s solution to that problem? How has he acted to save us from it?

- How do I—myself, right here, right now—how do I come to be included in that salvation? What makes this good news for me and not just for someone else?

We might summarize these four major points like this: God, man, Christ, and response. (30-31)

First the bad news: God is your Judge, and you have sinned against him.

And then the gospel: but Jesus has died so that sinners may be forgiven of their sins if they will repent and believe in him. (36)

Personally I don’t think Gilbert’s gospel, his reading of Romans fits the text very well.

I acknowledge there is a general movement from God’s wrath at sinful Gentiles and Jews to sinners being justified by grace through the redemption in Christ Jesus and justification by faith (Rom 1.18-3.26). But …

Gilbert has failed to note Paul’s Roman audience are commended as a faithful community of believers, which means Paul’s intention is not about telling them how they can be justified or be included in Christ’s salvation, because in his understanding they already are.

Gilbert has failed to note Paul is for the most part responding to a Jewish interlocutor who has condemned Gentiles and there are at least two rhetorical exchanges between them. If you read the apostles sermons in Acts you will note their gospel never includes a rhetorical exchange with an imaginary Jew in the gospel presentation. I’m saying this because Romans 1-4 is primarily a dialogue between Paul and this Jew in front of a believing audience and I fail to see how this is the gospel.

Gilbert has failed to note Paul says a lot which would concern the relationship between the believing Jews and Gentiles in his target audience. Personally I think Paul wants the Jew and Gentile believers in Rome to know their common faith in Jesus is how they can know they are righteous in God’s sight and this is what unites them.

Just because a square peg can be made to fit in a round hole, doesn’t mean it is the best fit for the hole. Gilbert’s four step gospel may be clear and plausible and I fear this will mislead others to believe him. But Paul warns us to beware plausible arguments (Col 2.4), we need to look closely at the text of Romans to see if what he says is true.

Just because a square peg can be made to fit in a round hole, doesn’t mean it is the best fit for the hole. Gilbert’s four step gospel may be clear and plausible and I fear this will mislead others to believe him. But Paul warns us to beware plausible arguments (Col 2.4), we need to look closely at the text of Romans to see if what he says is true.

If one takes a close look at the text of Romans 1-4 it’s obvious Gilbert’s reading does not take into account a number of its important features. There is an irreducible complexity to Romans 1-4 that cannot be dumbed down into four steps, let alone be judged to be Paul’s gospel.

Gilbert’s reading of other Gospel passages

After supposedly summarising four basic steps for presenting the gospel from Romans 1-4, Gilbert moves on to show the same sequence in other passages.

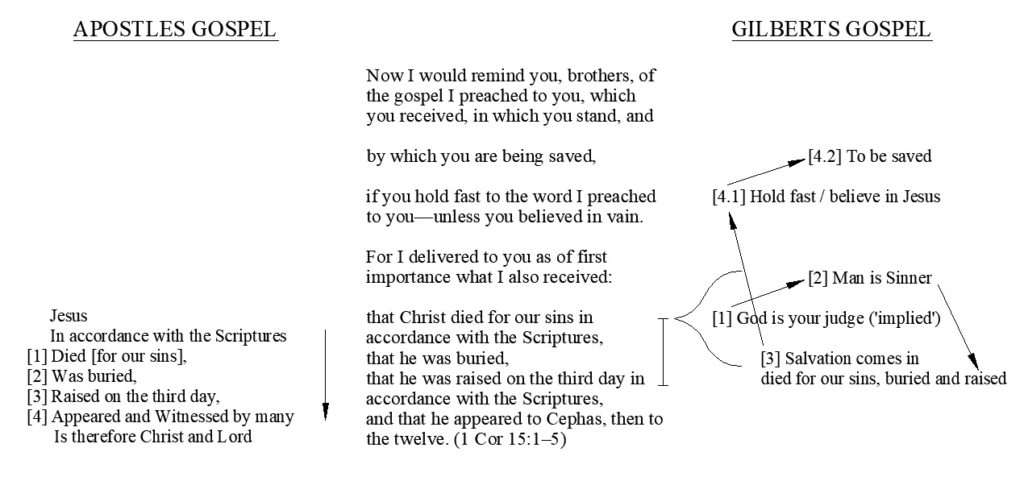

1 Cor 15.1-5

First Corinthians 15 is the first place I would go to for an outline of the gospel.

Do you see the central structure there? Paul is not as expansive as he is in Romans 1–4, but the main contours are still clear.

- [2] Human beings are in trouble, sunk in “our sins” and in need of “being saved”

- [1] (obviously, though implicitly, from God’s judgment).

- [3] But salvation comes in this: “Christ died for our sins . . . was buried . . . was raised.”

- [4] And all this is taken hold of by “hold[ing] fast to the word I preached to you,” by believing truly and not in vain.

So there it is: [1] God, [2] man, [3] Christ, [4] response. (32)

Gilbert practically displays a circular reading to the text to make it fit his four step gospel. He virtually attached no significance to the statement ‘according to the scriptures’ and Christ’s appearances. I think both of these are significant for Paul’s gospel.

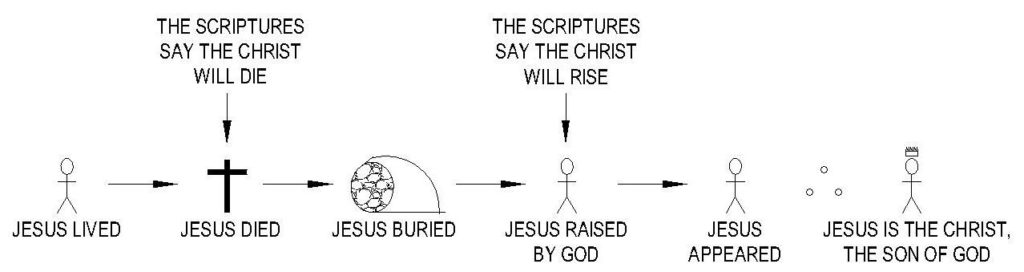

I think from this gospel outline (as I’ve highlighted in numerous places) Paul’s gospel has

- at least a four point narrative structure of significant events in Jesus’ life (death, burial, resurrection and appearances/witness),

- it identifies him as the Christ and

- argues this is in accordance with the Old Testament scriptures.

I argue the point of the gospel is to declare him Christ and Lord because that is what the apostles say (Acts 17:2–4; 18.5, 28; Jn 20:30–31; Rom 1:1–5; 10:8–11). The objective in sharing the gospel is more than just recognising him as Saviour, Paul is after the ‘obedience of faith’ (Rom 1.5; 15.18; 16.26) – that is what counts is embodied allegiance to Jesus as the risen Christ and Lord (Gal 5.6; 1 Cor 7.19).

Gilbert will go on to impose his framework on Acts 2.38; 3.18-19; 10.39-43 and Acts 13.38-39. He quite often will say things are implied and jumps around the passage, sometimes the end, then back up to the start, just to make it fit to his God-man-Christ-response formula.

I feel he concentrates on the salvation aspects of the message and not how the apostles refer to Christ’s death, burial, resurrection and appearances and the Old Testament scriptures as mentioned in Paul’s gospel outline.

For me I’ve also looked at the sermons in Acts in my series. I’ve highlighted the similarities to 1 Cor 15 here and shown what they do not say here. I’m not impressed with Gilbert’s reading of these passages.

Paul’s speech in Acts 13 is the closest to his outline of the gospel in 1 Cor 15 so I will highlight Gilbert’s treatment of it.

Paul, too, preaches the same gospel in Acts 13:

Therefore, my brothers, I want you to know that through Jesus the forgiveness of sins is proclaimed to you. Through him everyone who believes is justified from everything you could not be justified from by the law of Moses. (vv. 38–39 NIV)

Once again, the clearly recognizable framework is God, man, Christ, and response.

You need God to grant you “forgiveness of sins.” That happens “through Jesus,” and it happens for “everyone who believes.” (33)

Paul’s whole address is in verses 16-41. Gilbert clearly ignores much of it and jumps to the part of Paul’s speech that has anything remotely to do with salvation and starts importing and modifying it to fit his framework.

I on the other hand go straight for Acts 13:26–33 which is most similar to Paul’s outline in 1 Cor 15;

| 26 “Brothers, sons of the family of Abraham, and those among you who fear God, to us has been sent the message of this salvation. | |

| 27 For those who live in Jerusalem and their rulers, because they did not recognize him nor understand the utterances of the prophets, which are read every Sabbath, fulfilled them by condemning him. | They did not recognise him (as the Christ), nor

understand the scriptures which referred to him. (‘According to the scriptures’) |

| 28 And though they found in him no guilt worthy of death, they asked Pilate to have him executed. | [1] Jesus died |

| 29 And when they had carried out all that was written of him, they took him down from the tree and laid him in a tomb. | [2] Was buried |

| 30 But God raised him from the dead, | [3] Was raised |

| 31 and for many days he appeared to those who had come up with him from Galilee to Jerusalem, who are now his witnesses to the people. | [4] Appeared to many |

| 32 And we bring you the good news that what God promised to the fathers, 33 this he has fulfilled to us their children by raising Jesus | (Good news = God’s promises have been fulfilled in Christ’s resurrection) |

In my reading Paul is telling the story of Jesus’ life, death, burial, resurrection and appearances, arguing from the old testament that God’s promises have been fulfilled and Jesus is the Davidic Son of God. Only after these points are made does Paul say that through him is forgiveness and justification from sin. This is hardly you have a problem with sin, God’s solution is found in the death and resurrection of Jesus.

Paul first provides a narrative proof that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God. Then he talks about the blessings that follow from recognising him as Christ and warnings against rejecting him.

In the next part of the book Gilbert will continue on to draw upon his four steps. These steps are: God the Righteous Creator, Man the Sinner, Jesus Christ the Savior and Response—Faith and Repentance. I’ll ignore these as they operate on the assumption the four steps he has argued are the gospel.

Gilbert’s Center

Gilbert has a chapter called, ‘Keeping the Cross at the Center’ which warrants some attention, because in it he attempts to pick apart other gospels presented today.

Indeed I believe one of the greatest dangers the body of Christ faces today is the temptation to rethink and rearticulate the gospel in a way that makes its center something other than the death of Jesus on the cross in the place of sinners. (102)

Personally I don’t think the center is the death of Jesus on the cross in the place of sinners (i.e. Substitutionary atonement).

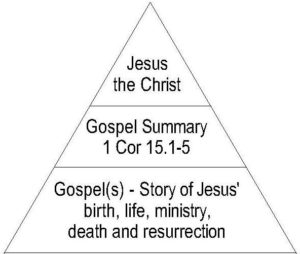

I think Jesus Christ himself is the center. Jesus (Christology) is central, not personal salvation (Soteriology).

This diagram shows my thinking in a progressive broadening of what the apostolic gospel is.

The gospel the apostles preached is Jesus Christ. If Jesus Christ is not preached the gospel is not preached.

In John’s gospel, Jesus is the Word of God, he is the message, the word of life. This means He is the Gospel. Jesus’ ‘I am’ statements reflect the same idea. When Jesus proclaims himself, he is proclaiming the gospel.

The next level down is the outline and summary of the gospel as described by Paul in 1 Cor 15.3-5. These reflect the naming of Jesus as the Christ, the narrative of his death, burial, resurrection, appearances, and also his future return and judgement (1 Cor 15.24-28). This story is ‘according to the scriptures’ – it has fulfilled the scriptural promises and prophecies of the Old Testament.

Down again and broader still are the bibliographies of Jesus which are named the gospel. The biographies of Jesus describe much about his unique birth, miracles, powerful ministry, teachings, crucifixion, death and resurrection.

The biographies give much greater exposure to Jesus and describe many aspects of salvation throughout (e.g. Mk 2.5; Lk 2.11; 24.47; Jn 3.16; 4.22). A reading of the whole gospel will constantly expose readers and listeners to varied applications of the gospel.

The significant amounts of Christ’s teachings and commands help people mature and grow in their faith. Hence this level of gospel promotes not only the initial salvation of sinners by believing Jesus is the Christ, but also matures existing Christians in the faith.

It looks like Gilbert has a beef with a ‘bigger’ gospel. I guess therefore the two lower levels of my understanding.

The pressure to do that is enormous, and it seems to come from several directions. One of the main sources of pressure is the increasingly common idea that the gospel of forgiveness of sin through Christ’s death is somehow not “big” enough—that it doesn’t address problems like war, oppression, poverty, and injustice. (102)

This ‘bigger’ gospel must be bigger than personal salvation for Gilbert I assume and also handle the problems of creation – war, oppression, poverty and injustice. Personally I’m inclined to think it’s a both/ and rather than an either / or Gilbert seems to be pushing. He then says;

All those problems are, at their root, the result of human sin, and it is folly to think that with a little more activism, a little more concern, a little more “living the life that Jesus lived,” we can solve those problems. No, it is the cross alone that truly deals once and for all with sin, and it is the cross that makes it possible for humans to be included in God’s perfect kingdom at all. (102)

The cross alone does not deal with the problem of sin. The Holy Spirit also. What he says sounds nice and may make one popular in reformed circles, but the proof of the pudding is to compare it with scripture. The cross removes the penalty for sin (forgiveness), the Spirit deals with the power (progressive sanctification) and the presence of sin (resurrection).

Then he takes on the gospel which says, ‘Jesus is Lord’;

It should be obvious by now that to say simply that “Jesus is Lord” is really not good news at all if we don’t explain how Jesus is not just Lord but also Savior. Lordship implies the right to judge, and we’ve already seen that God intends to judge evil. Therefore, to a sinner in rebellion against God and against his Messiah, the proclamation that Jesus has become Lord is terrible news. It means that your enemy has won the throne and is now about to judge you for your rebellion against him. For that news to be good and not simply terrifying, it would have to include a way for your rebellion to be forgiven, a way for you to be reconciled to this One who has been made Lord. That’s exactly what we see in the New Testament—not just the proclamation that Jesus is Lord, but that this Lord Jesus has been crucified so that sinners may be forgiven and brought into the joy of his coming kingdom. Apart from that, the declaration that “Jesus is Lord” is nothing but a death sentence. (104)

This is plain wrong. People don’t need to know Jesus is saviour or understand the mechanics of his atoning death in order for him to save them. All is required is allegiance to him as Christ and Lord (Jn 20.31; Rom 10.9-10). Note I’m not denying Jesus is saviour, I’m denying people have to recognise they are sinners and him as saviour as well as the mechanics of atonement for them to be saved. Again here.

Recommendation

Gilbert’s gospel is a fine example showing that people believe what they want to believe. In the wrong hands the scriptures can be ignored, added to, modified and subverted to fit any purpose the interpreter desires.

In his reading of Romans, in order to produce the ‘gospel’ he cuts out the bits he doesn’t need, reorients who Paul is speaking too, adds bits that are missing and jumps back and forth to produce the sequence he wants. The key questions to ask about Gilbert concern his objectivity in approaching the scriptures and how much he has to lose if he is wrong on the gospel.

Gilbert moves the center of the gospel away from the person of Jesus, his words and deeds and locates it with personal salvation. In the end, for him the gospel is all about us.

Gilbert’s gospel was nowhere believed for the majority of the history of Christianity. No one believed this was the gospel from the early church fathers, right up until the reformers. It’s a modern creation that has evangelicalism in a headlock.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2017. All Rights Reserved.