This book greatly helps its readers to understand the dominant cultural influences on the early church and serves as an excellent set of lenses by which to to interpret the New Testament. I recommend this book for students as an introduction to new testament studies as a whole.

This book greatly helps its readers to understand the dominant cultural influences on the early church and serves as an excellent set of lenses by which to to interpret the New Testament. I recommend this book for students as an introduction to new testament studies as a whole.

- Link: Amazon

- Length: 320

- Difficulty: Medium

- Topic: Historical, Interpretation

- Audience: Educated Christians

- Published: 2000

To a large degree DeSilva is interacting with Greco-Roman cultural values. As the title of the book says, these cultural values are:

- Honor-Shame (Social ethics and standards),

- Patron-Client relationships (Grace, reciprocity and faith),

- Kinship bonds (Family, sonship), and

- Purity (Holiness, clean, unclean, defilement, washings).

DeSilva’s work on patron-client relationships and how they properly influence how we ought to understand grace and faith is one of the groundbreaking studies that has only recently been given much wider recognition.

Works such as Barclays, Paul and the Gift (review), NT Wright’s, Paul and the Faithfulness of God (review) and especially Richards and O’Briens, Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes (review) are following in his footsteps at least a decade afterwards and further developing his research.

DeSilva’s basic structure of each of his main sections is to highlight the how the particular theme he is concentrating on is:

- portrayed in its historical context and culture,

- show how this is reflected in the New Testament, and

- how it applies for us today.

This post is one of my book reviews.

Contents

Introduction: Cultural Awareness & Reading Scripture

In the first section DeSilva lays down his argument for why we ought to learn about the historical context and culture in order to properly interpret the New Testament. He defines culture as the ways in which people look at the world and the framework for all communication. We can see from this why understanding the culture of first century Israel will help us better understand the NT.

Words, expressions and manners of speech are devices which communicate meanings from one person or group to another. To communicate properly the meaning of the word or expression has to be understood by both parties. DeSilva hopes to explain the dominant framework and understandings that shape communication and values in the New Testament era.

Throughout his book DeSilva bases his understanding of the New Testament context by extensively referring to Greek, Romans and Jewish teachers such as Seneca, Quintilian, Ben Sira, and Aristotle.

1. Honor & Shame: Connecting Personhood To Group Values

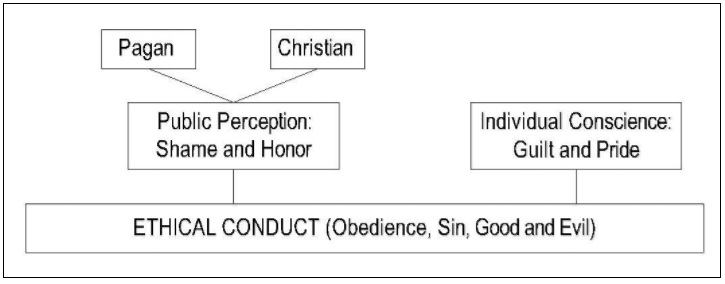

Our modern western culture is largely individualistic and our ethics personal and guilt oriented. People in the New Testament era were more focussed however on their social standing. Rather than feeling pride or guilt, they felt honor and shame particularly when what they had done was made public.

In this chapter DeSilva defines Honor as self respect and the respect of others. A person experiences shame when they have behaved contrary to group norms and consequently viewed as less valuable. Shame concerns losing face. Both are feelings resulting from social pressure.

While the powerful and the masses, the philosophers and the Jews, the pagans and the Christians all regarded honor and dishonor as their primary axis of value, each group would fill out the picture of what constituted honorable behavior or character in terms of its own distinctive set of beliefs and values, and would evaluate people both inside and outside that group accordingly. (25)

DeSilva highlights that different groups have different values. Sometimes these values overlap, sometimes they are different.

2. Honor & Shame In The New Testament

2 looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God. 3 Consider him who endured from sinners such hostility against himself, so that you may not grow weary or fainthearted. (Heb 12.2-3).

Like each of the New Testament chapters to come, in this chapter DeSilva shows how Christ has redefined the ethical understandings which underpin honor and shame among Christians. The concepts of honor and shame still apply, but the behaviours and attitudes which result in honor and shame have evolved.

These chapters on honor and shame are largely about ethics. DeSilva argues the early Christians were frequently encouraged to live worthily of the gospel and Jesus with the final judgment in view. I’m not sure if DeSilva is a protestant, but for me normally discussions revolving around ethics, especially with reference to the final judgment, will tend to downplay the role of personal behaviour and ethics in this judgment (e.g. salvation by grace through faith alone). DeSilva seems to go against the protestant current here. Which I found faithful to the text.

DeSilva highlights differing people groups have differing understandings of what is honourable and shameful. What the world might think as shameful, Christians might think of as wonderful. So Christians will be at odds with the society around them, unbelievers may shame them, and believers may be tempted to revert back to the world. The authors of the NT therefore spend a lot of time and energy to make sure their audiences pursue what God values as honourable and protect their audiences from outside influences.

3. Patronage & Reciprocity: The Social Context Of Grace

“Someday, and that day may never come, I will call upon you to do a service for me. But until that day, accept this justice as a gift on my daughter’s wedding day.” (The Godfather)

These next few chapters interested me the most as they concerned grace and faith framed through the perspective of Patronage.

DeSilva explains that patron – client relationships were quite common in the Greco-Roman era. They were used mainly to provide special products or services that were not provided in the marketplace. The relationship was initiated by the patron when he gives a gift to his prospective client.

For the actual writers and readers of the New Testament, however, grace was not primarily a religious, as opposed to a secular, word. Rather, it was used to speak of reciprocity among human beings and between mortals and God (or, in pagan literature, the gods). …

[1] First, grace was used to refer to the willingness of a patron to grant some benefit to another person or to a group. In this sense, it means “favor,” in the sense of “favorable disposition.” …

[2] The same word carries a second sense, often being used to denote the gift itself, that is, the result of the giver’s beneficent feelings. …

[3] Finally, grace can be used to speak of the response to a benefactor and his or her gifts, namely, “gratitude.” (104) … Receiving a favor or kindness meant incurring very directly a debt or obligation to respond gratefully, a debt on which one could not default. (109)

Barclays, Paul and the Gift (review) is my benchmark for evaluating DeSilva’s depiction of grace. Yet credit should be given to DeSilva because he highlighted many aspects of grace well before Barlclay did.

Barclays, Paul and the Gift (review) is my benchmark for evaluating DeSilva’s depiction of grace. Yet credit should be given to DeSilva because he highlighted many aspects of grace well before Barlclay did.

DeSilva above lists several overlapping instances of what are now know as Barclays ‘perfections’: Singularity, superabundance, efficacy and reciprocity.

In particular I find it helpful to remember the more common words used for the relationship: ‘Grace’, ‘favour’ and ‘gratitude’. We should note again the public context of the gift and relationship, which brings in the honour / shame framework. The public reputation of both parties is in view. Lastly the same word can denote two related actions (e.g. ‘grace met with grace’). The act of giving as well as the response.

It is worth noting at this point that faith (Lat fides; Gk pistis) is a term also very much at home in patron-client and friendship relations, and had, like grace, a variety of meanings as the context shifted from the patron’s faith to the client’s faith. (115)

DeSilva goes on to say ‘faith’ was generally understood to mean ‘dependability’, ‘loyalty’ and ‘trust’.

I think it helpful at this point to refer to Bates’ book, Salvation by Allegiance Alone (review). (Again, DeSilva’s work came out many years before Bates’.) Bates argues where faith is associated with salvation it most likely means ‘allegiance’. Loyalty to Christ as king. It seems DeSilva’s understanding of faith, as depicted in a patron-client relationship is similar. Of course DeSilva also refers to trust which is the traditional protestant understanding of faith.

I think it helpful at this point to refer to Bates’ book, Salvation by Allegiance Alone (review). (Again, DeSilva’s work came out many years before Bates’.) Bates argues where faith is associated with salvation it most likely means ‘allegiance’. Loyalty to Christ as king. It seems DeSilva’s understanding of faith, as depicted in a patron-client relationship is similar. Of course DeSilva also refers to trust which is the traditional protestant understanding of faith.

DeSilva describes the tacit expectations associated with the gift giving and return. Normally the patron will give to a prospective client who has a good reputation, who is considered worthy and is likely to value the relationship. The client likewise is under pressure to reciprocate and to give the patron their due (service and praise). Their reputation for gratitude and having a grateful heart is at stake.

However on the other hand DeSilva also highlights the ideal for the patron – client relationship is for the patron to give irrespective of the worthiness of the client and likelihood of reciprocity. Likewise the client is expected to show loyalty to the Patron despite the possible consequences of supporting a patron who may have fallen on tough times or ill repute.

‘The point is that the giver should wholly be concerned with giving for the sake of the other, while the recipient should be concerned wholly with showing gratitude to the giver.’ (117)

These relationships seemed to be created and maintained in part to promote civilised, noble and virtuous conduct. Each of the parties are intended to behave the way they do because the relationship itself is beautiful.

4. Patronage & Grace In The New Testament

8 For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, 9 not a result of works, so that no one may boast. 10 For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them. (Eph 2:8–10)

God’s action in Christ is the supreme act of his grace. Christ and the salvation he brings is God’s gift to us. In this chapter  DeSilva speaks specifically about grace. But his discussion of what God is doing is very similar to NT Wright’s understanding of the ‘righteousness of God’. Where Wright argues the righteousness of God is God’s demonstrating his faithfulness to his covenant promises through Christ’s life, death and resurrection in the gospel.

DeSilva speaks specifically about grace. But his discussion of what God is doing is very similar to NT Wright’s understanding of the ‘righteousness of God’. Where Wright argues the righteousness of God is God’s demonstrating his faithfulness to his covenant promises through Christ’s life, death and resurrection in the gospel.

In the next few chapters DeSilva distinguishes the New Testament understanding of grace from its historical contemporaries.

Incongruity. His first and most important observation is that God’s grace is given to the unworthy. Normally a patron would give to someone with a reputation for a grateful heart, someone who would reciprocate appropriate. God gives to his enemies, sinners who are in rebellion against him.

Priority. In many instances the client will initiate the relationship with the patron by requesting a favour. In the New Testament God reverses this trend. He is the one who demonstrates the initiative. Exercising priority and giving to unworthy sinners.

Towards the end of the chapter DeSilva expands on several facets of God’s grace. These include those given at the start of the relationship and those during the relationship.

While DeSilva’s discussion on grace and faith was interesting, unfortunately I found he did not spend much time discussing particular grace and faith passages in particular in Paul’s letters.

5. Kinship: Living As A Family In The First-Century World

12 Therefore let us lie in wait for the righteous; because he is not for our turn, and he is clean contrary to our doings: he upbraideth us with our offending the law, and objecteth to our infamy the transgressings of our education. 13 He professeth to have the knowledge of God: and he calleth himself the child of the Lord. (Wis 2:12–13. KJV)

In this chapter DeSilva investigates several aspects of kinship in the Greco-Roman era.

He highlights a person’s family often determined their perceived social worth and identity. He speaks about the makeup of households. Father, wives, children (sons and daughters) and slaves. Families often worked together in various trades. He speaks about the interrelationships in the family. In particular I found his discussion of marriage and women quite interesting. It further confirmed my suspicion the Greek and Roman cultures were patriarchal with women taking an inferior place to men.

‘Like father, like son’. It’s a common expression which highlights sons inherit characteristics from their fathers and these traits can be used to distinguish families bound together by characteristics other than blood.

The nature of kinship—that is, what really constitutes kinship—was a frequent topic of debate in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. It became commonplace to place more emphasis on the similarity of character that bound siblings together rather than relationship merely by blood (see 4 Macc 13:24–26), from which it became an easy step to claim that such kinship of character was enough to create kinship. (194)

A little later DeSilva quotes the great passage above from Wisdom of Solomon showing Jew’s of that time did believe ‘the righteous’ were ‘children of God’. He explains this is an example of ‘fictive’ kinship as opposed to natural kinship. This has implications for how we understand kinship in the NT and especially some of Paul’s passages in Romans and Galatians.

6. Kinship & The “Household Of God” In The New Testament

49 And stretching out his hand toward his disciples, he said, “Here are my mother and my brothers! 50 For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.” (Mt 12:49–50)

7 Know then that it is those of faith who are the sons of Abraham. (Gal 3.7)

DeSilva begins by explaining in the New Testament, the Jewish concept of kinship is reworked around Christ.

This opens up his discussion of Gentiles now being included in the family of God. Gentiles being linked to Abraham and God’s promises. Jews and Gentiles living together as brothers and sisters in Christ. How Christ and the apostles have now understood marriage, remarriage and household ethics.

7. Purity & Pollution: Structuring The World Before A Holy God

10 You are to distinguish between the holy and the common, and between the unclean and the clean, 11 and you are to teach the people of Israel all the statutes that the LORD has spoken to them by Moses.” (Lev 10:10–11)

DeSilva begins this chapter explaining our own cultures purity maps. Things and behaviours we would normally consider clean and unclean.

From this starting point he then discusses the purity maps which would normally be viewed as strange and foreign to us.

Purity codes are a way of talking about what is proper for a certain place and a certain time (however one’s society fills in the content). Pollution is a label attached to whatever is out of place with regard to the society’s view of an orderly and safe world. Purity has to do with drawing the lines that give definition to the world around us, distinguishing, for example, what belongs to an individual from what belongs to others, and then defending these lines from being crossed by unwelcome forces. (243)

When DeSilva approaches the first century he begins with the Greeks and Romans to demonstrate they too had their own understandings of what was clean or unclean. But for the most part his discussion was on the Jewish world, as one would expect.

DeSilva outlines the main facets of purity in the OT. The temple, laws governing what is holy and defiled, clean and common and the washings and sacrifices required to regain holiness and cleanliness. He helpfully explains this was part of everyday life for the Hebrew people, well into the NT.

8. Purity & The New Testament

4 But when the goodness and loving kindness of God our Savior appeared, 5 he saved us, not because of works done by us in righteousness, but according to his own mercy, by the washing of regeneration and renewal of the Holy Spirit, 6 whom he poured out on us richly through Jesus Christ our Savior, (Tit 3:4–6)

22 Do not be hasty in the laying on of hands, nor take part in the sins of others; keep yourself pure. (1 Tim 5:22)

27 Religion that is pure and undefiled before God the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world. (Jas 1:27)

DeSilva says the Gospels contain numerous instances where Jesus intentionally challenged the maps of persons, foods, times and space of his surrounding culture. Regarding people he associated with sinners and Gentiles. He enabled the Jewish believers to associate with Gentile believers (Acts 10,11,15). Regarding foods, he declared them clean, saying only what comes out of a person’s heart makes them unclean (Mk 7). Jesus’ death on the cross gives the same standard of cleanliness and purity normally associated with high priests on the day of atonement (Heb 10).

DeSilva discusses baptism, the now and not yet tension (liminality) believers live in, idolatry, sexual immorality, and greed.

Have you ever heard someone define righteousness, ‘as if I’d never sinned’. During his discussion DeSilva rightly corrects this assumption. It’s true, in the OT, righteousness is normally listed with innocence (see my word study here), but ‘righteousness’ properly reflects the practice of righteousness (e.g. 1 Jn 3.7), not the absence of sin.

That is to say, holiness, ethically and cultically speaking, is the absence of defilement or blemish (separation from what displeases or provokes the holy God). It would generally fall to words such as righteousness to capture the active aspects of Christian ethics, the positive pursuit of good works, acts of love and service, and the like. (297)

Towards the end DeSilva summarises the two main heads of how the New Testament authors deal with purity. They concern:

- Jesus’ and our mission to sinners, and

- The churches abstinence from defilement.

Conclusion

DeSilva ends his book with a quick summary and overview of the whole. It serves as a good reminder of the whole.

Recommendation

I benefited a lot from reading this book. I found it fairly easy to read. There was not much theological jargon. I think most could get through it easily.

DeSilva on the whole seems to be a traditional protestant. This particularly comes out on his discussions on Romans, Galatians and Baptism. However, several things he says suggest he the way we live know will have a bearing on the final judgment.

He has a great breakdown of the nuances of grace in the patron-client relationship. That being said, I would have liked to see some examples of how the patron-client perspective influences how we understand Pauline grace and faith passages. He gives a excellent description of the relationship, but does not apply it as much as one would hope. I suggest his upcoming commentary of Galatians will draw these out.

Sometimes I felt he over exaggerated the influence a theme had over certain passages.

Overall I found it helped me focus on key themes which permeate the Old and New Testaments. It provides a great set of lenses by which we can interpret the New Testament. I especially recommend this book for students of the New Testament as it will give them a good background to studying the gospels.

Copyright © Joshua Washington and thescripturesays, 2018. All Rights Reserved.

Quotes taken from Honor, Patronage, Kinship & Purity by David A. deSilva. Copyright (c) 2000 by David A. deSilva. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515, USA. www.ivpress.com